On Jan. 31, 2023, Afrodita Foster woke up just before 7 a.m., as she regularly did.

She walked into her son Cayden’s room to make sure he was awake and getting ready for school. Cayden attended Centreville High School in Fairfax County, Virginia.

She recalls thinking the room was too quiet. She walked toward him, urging him to wake up, because he needed to be ready for class.

As she got closer, she saw his phone was on his chest. She reached for it, and noticed Cayden’s hand was very cold. His shoulder was cold, too.

She tried to wake him but was unsuccessful.

Cayden’s parents say he was a happy and normal teenager. He was excited about the prospect of college, hoping to attend an SEC school. He was usually the designated driver, and his friends told Cayden’s parents he didn’t even like the taste of alcohol.

When police arrived to the Foster home that morning, they took Cayden’s phone, which had a wallet sleeve behind it. That’s where he kept his driver’s license and credit card. There was also a $1 bill folded over, Sean Foster, Cayden’s dad, said. It had two blue pills inside that looked like Percocet.

A toxicology report later found there was nothing in Cayden’s system but fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid often pressed into counterfeit pills.

“We had a life before this happened, and we have a very, very different life now,” Afrodita told WTOP. “Cayden was our only child. It’s horrible. It’s not something that anybody should go through.”

In the months since Cayden died, the Fosters have worked to make sure other parents don’t experience similar heartbreak. Schools across the D.C. region have hosted information sessions about the dangers of fentanyl, and are continuing to do so. Fairfax County has an opioid awareness session scheduled next week.

“Just trying to get the word out to people, because we really don’t have anything left,” Sean said. “It’s really kind of taken away any degree of purpose for our future.”

Neither Sean nor Afrodita saw any warning signs. They described Cayden as a good student, who didn’t get in trouble. Afrodita periodically checked his room, backpack and pockets, but never found anything concerning. The family spoke about drugs several times. Sometimes, Sean said, Cayden would say things like, “I don’t understand how people can do that to themselves.”

The Fosters have since learned that the people involved with either getting Cayden to take the pills or selling them to him had been doing it for years. They did it with students at Centreville High and would do it in the parking lot when they returned from college.

Cayden met one person who Sean suspects was involved through a classmate’s friend. Conversations about what college is like at some point turned into talks about drugs, specifically Percocet, Sean said. Many of the transactions happened using the social media app Snapchat.

“When Cayden got started with this, he had friends that were aware that this was occurring,” Sean said. “Nobody told the school resource officer. Nobody told their own parents. … Now, because nobody said anything, we’re dealing with a dead child…”

“I will never understand why he decided to take that pill,” Afrodita said. “You don’t know what you’re really taking. Your friend might tell you that it is a Percocet or Xanax or Adderall, but they cannot know what is in the pill.”

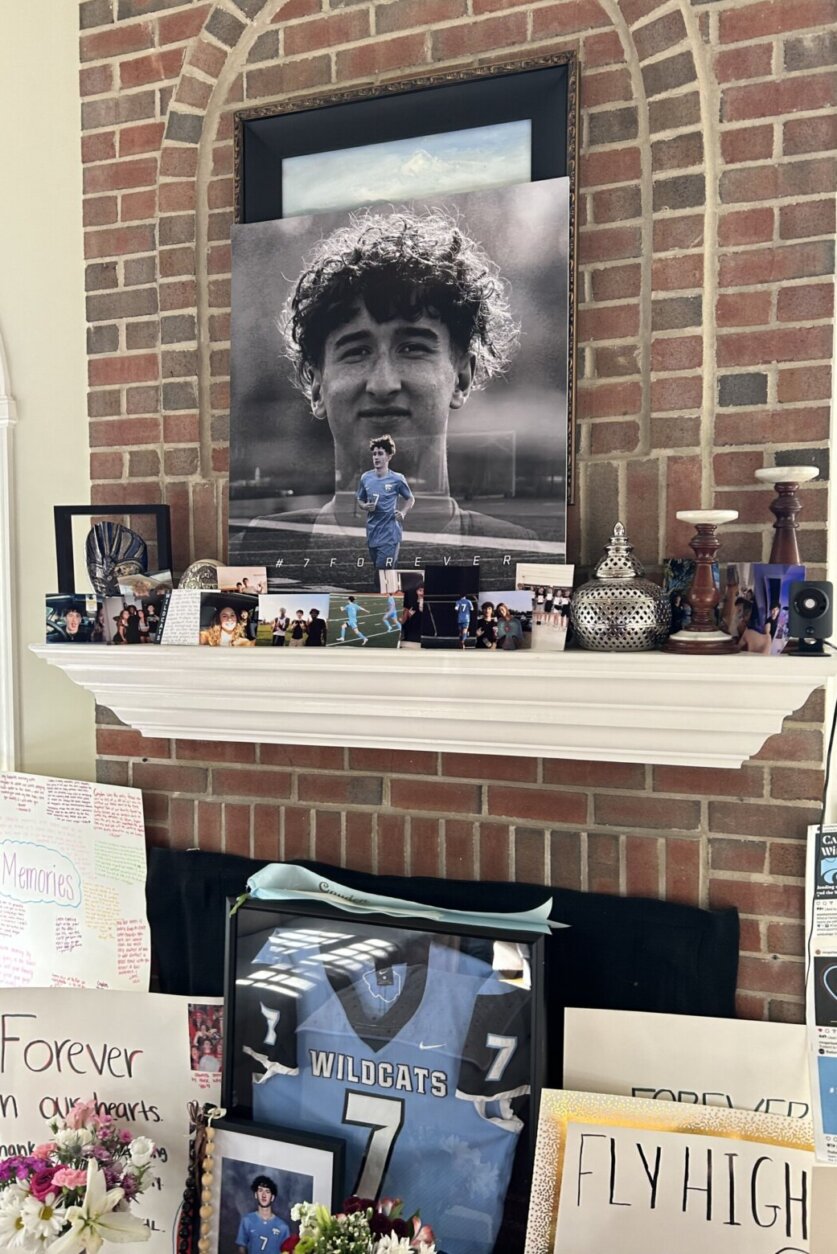

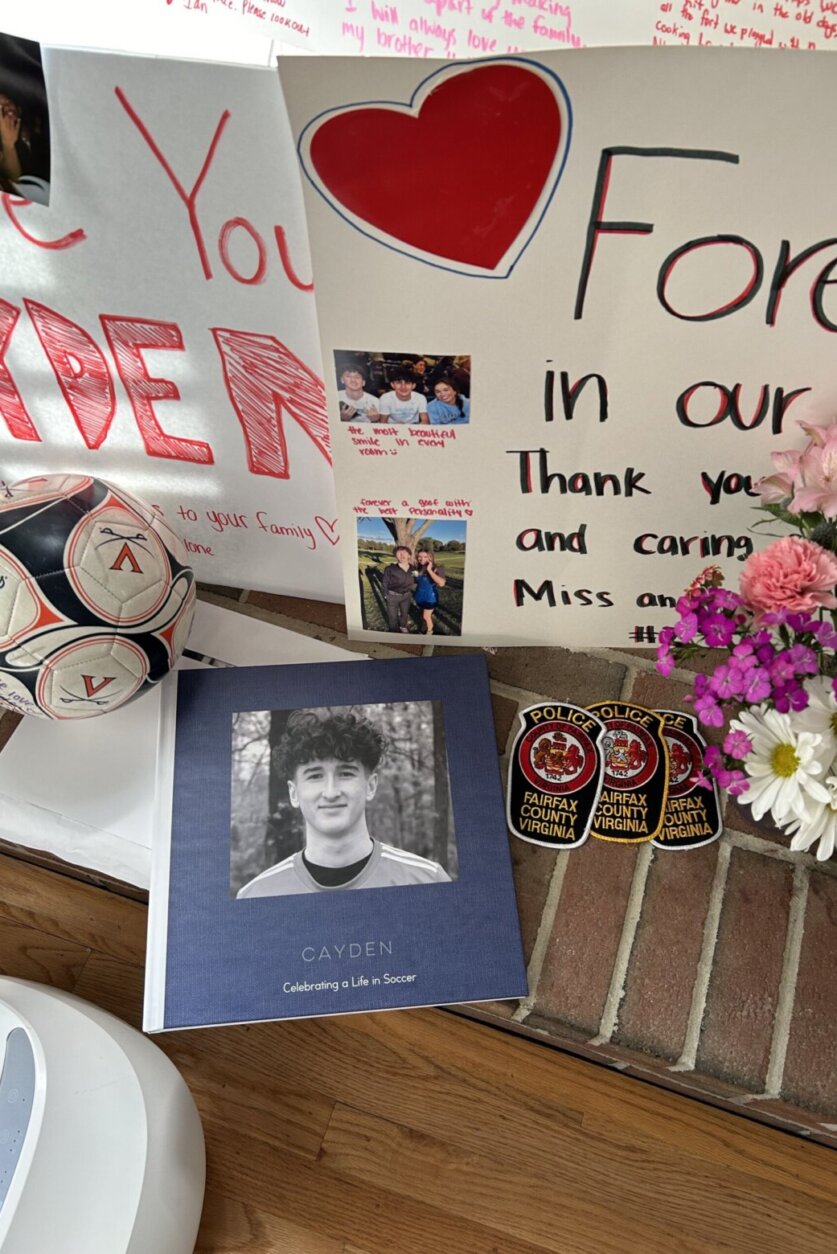

Two nights after Cayden died, a few of his friends told the Fosters they were planning to stop by. When the Fosters opened the door, there were 100 kids walking down the street with posters and flowers. Many of those items remain in the Fosters’ living room. There’s a poster with a collage of Instagram accounts showing support, a football jersey because Cayden played freshman football, and a drawing of Cayden and Afrodita holding hands, among other things.

Sean periodically looks at the displays. Afrodita tries not to.

“When you do focus on it, it’s a constant reminder that he’s not here,” Sean said. “It’s hard. You see pictures and they bring back memories. Then it reminds you that there’s not going to be any new ones.”

On May 20, what would’ve been Cayden’s 19th birthday, about 50 kids met at the cemetery. The Fosters felt their love. Many of Cayden’s friends invited them to their high school graduation parties, and they attended, because that’s what they knew Cayden would have wanted. But pain came with it.

“It did remind us of what we lost, several times,” Sean said. “There’s not going to be any more birthdays celebrated together. No more holidays celebrated together. There won’t be a college graduation or a wedding or grandkids. All that’s wiped away.”

The Fosters didn’t decorate their house for Christmas, because the holiday was always about Cayden, and Thanksgiving was their favorite family holiday, so they didn’t celebrate that either. Instead, they’re focused on advocacy.

For Sean, part of that includes advocating for a change to the Post-9/11 GI bill. He transferred his benefits to Cayden, who planned to attend college using it. Now, he learned he can’t “transfer them to another 18-year-old who’s about to go off to college, so they can go to college debt free and come out and be a productive member of society.”

He’s seeking an adjustment that would “allow me to find a deserving student to provide [the benefits to] so that they can go to college without having to go to loans.”

The Fosters are also urging students and parents to remain vigilant.

“Given how lethal this drug is, we didn’t have time to figure out there was a problem,” Sean said. “It was six weeks from the day Cayden first took a pill to the day he took the pill that killed him over the winter break last year.”

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.