CHANTILLY, Va. — “Gun belts and vests, go ahead and get them back on,” orders Fairfax County police 2nd Lt. Dan Pang, at the county’s Criminal Justice Academy.

Putting on the ballistic-looking vests and belts complete with blue rubber “guns” is a group of reporters who have been assembled here, myself included. Pang and other members of county police are running us through several scenarios they could encounter during their shift, as part of their inaugural Media Police Academy.

Their goal is to give us a deeper understanding of the dangers they face, the murky situations they deal with and the life and death decisions they may have to make. I can’t help but feel that our failure during the scenarios is inevitable, in order to have those messages driven home.

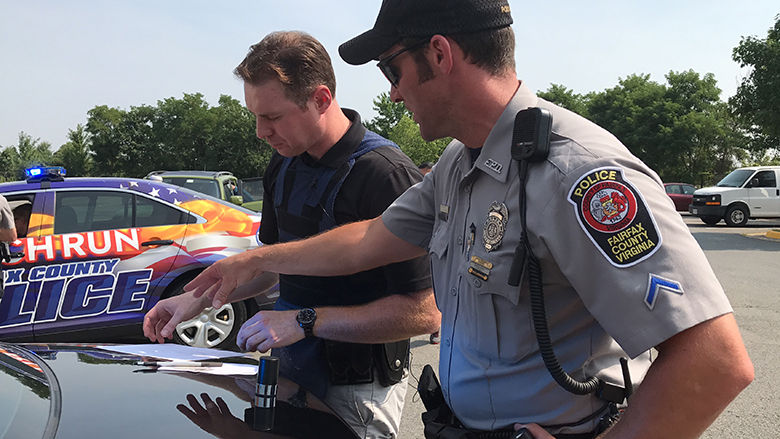

Our first simulation involves a traffic stop on the academy grounds.

“Hands are what kill us,” says Pfc. Mark Pollard. “That is the No. 1 thing I’m looking for, before I even turn my blue lights on.”

When it’s my turn, I step out of an unmarked Chevy Impala and approach a volunteer who’s playing the role of a driver with expired tags. Fully expecting an ambush, I approach cautiously. I stand next to the rear door, essentially hiding from any direct contact with the driver. I get to say ‘License and registration, please.’ He complies. I go back and write a ticket, and send him on his way.

“If you would have had your eyes on his hands the entire time, there’s no doubt in my mind you would have seen that gun,” Pollard says. “I don’t know until that traffic stop is over whether or not it’s a deadly encounter.”

We were also given crash courses in domestic violence calls and de-escalation, before attempting responses of our own.

Fairfax County police responded to 11,000 calls for domestic violence in 2016, according to Pfc. Monica Meeks.

“You’re dealing with people’s emotions, children, money, marriage,” she says. “They’ve been arguing about finances for years, they’ve been arguing about lack of sex, they’ve been arguing about how to raise the children.”

She says the problem affects every segment of society, and because of the emotions involved, it’s one of the most dangerous calls officers respond to.

In our scenario, two brothers are arguing over a bar tab inside a fake pizzeria that’s part of an entire fake strip mall inside the academy. We do as we were instructed, separating the two and getting their stories. One admits he kicked the other, making his arrest mandatory.

While that scenario was fairly straightforward, the de-escalation one was not. De-escalation has become a popular topic in recent years, with several officers’ actions making national news. Many people have asked why the officers did not de-escalate the situation instead of using force.

We arrive at the same scene and this time find a ranting man with a sledgehammer and a knife. Our attempts to start a dialogue fail. He charges at us repeatedly and the exercise comes to an end when my partner officer, WTOP’s Kathy Stewart, pulls her rubber gun and says “bang.”

“That is one of those split second decisions that you will second-guess yourself for the rest of your life,” Pang said.

Despite our best efforts, our attempts at de-escalation were unsuccessful, which was likely the point.

“You can’t get him to listen; you can’t get him to calm down. It’s not quite as easy as you think,” Pang said. “In the media sometimes, on social media, you will hear ‘Family called for their loved one who’s in crisis and the police showed up and killed him.’ But is it really that simple?”

He says the use of deadly force would have been justified in this case, although an electronic weapon like a Taser could have been used if another officer had a lethal weapon ready in case the electronic one failed. Officers must use their judgment to determine which threats are deadly, and those threats may not be as clear-cut as a gun or knife. As a result, their discretion in using deadly force is fairly broad.

I’m told a person swinging a piece of lumber or even a large metal pizza stand could reasonably cause an officer to fear for his or her life. I’m also told a major factor is whether other people are in danger, and that officers must act to keep others safe.

For many, any talk of use of force in Fairfax County leads to talk of the John Geer case. The Springfield, Virginia, resident was shot by police in the doorway of his home in 2013. Former officer Adam Torres pleaded guilty to the involuntary manslaughter of Geer, who was unarmed at the time of the shooting, and, according to witnesses, had his hands up. It took his family over a year to find out the shooting officer’s name.

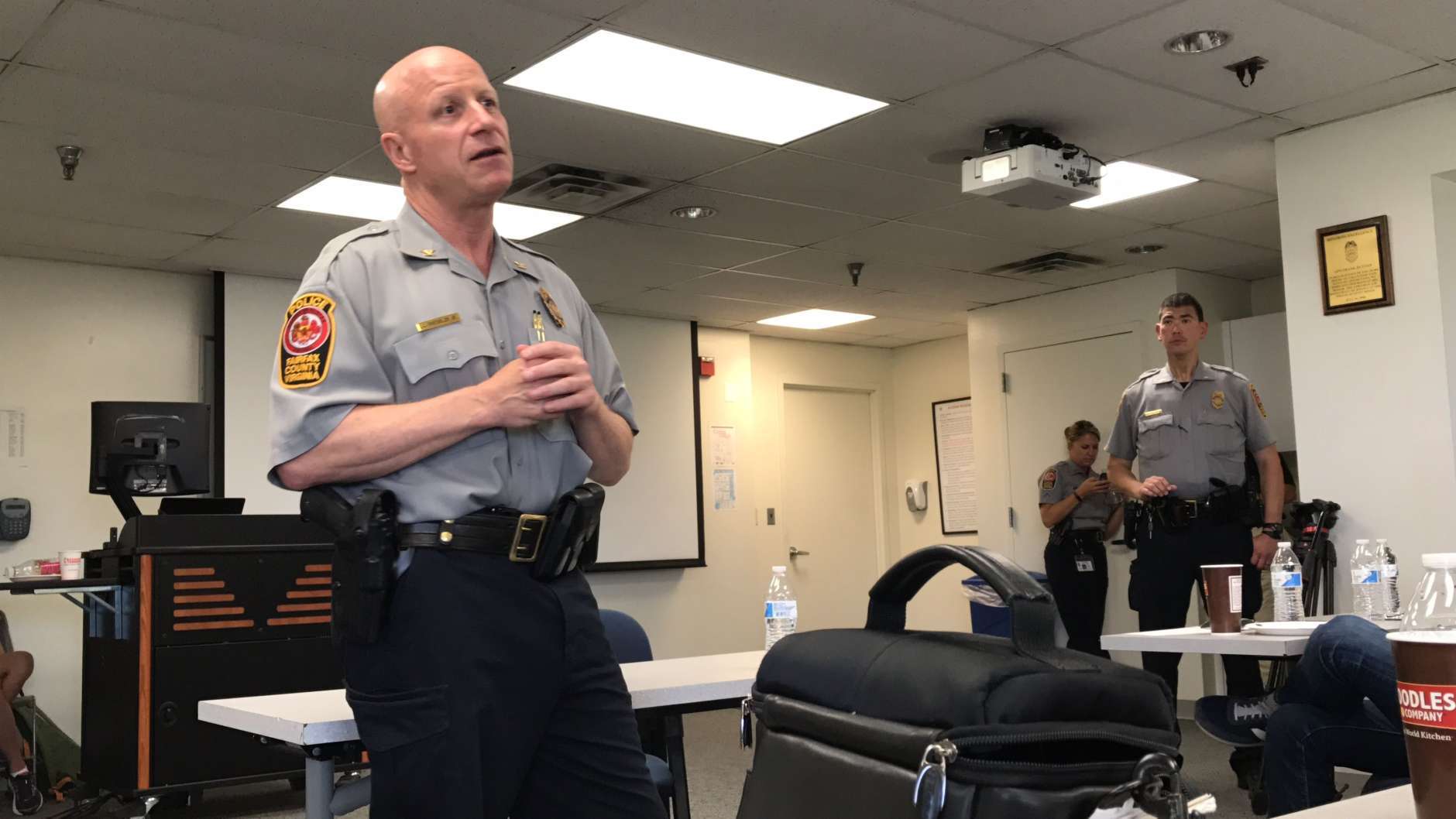

“Everyone’s familiar with the John Geer case, and hopefully over the last couple of years and as each event unfolds, you are seeing more transparency from the Fairfax County Police Department,” said Chief Ed Roessler. He points to his recent action of charging one of his officers with reckless driving, after a speeding police cruiser that did not have its lights and sirens on crashed into a minivan in Falls Church, injuring the driver.

The county has also formed a Police Civilian Review Panel, which Roessler says he and his officers support. The panel was created “as another way for residents to submit complaints concerning allegations of abuse of authority or misconduct by a Fairfax County police officer,” and is meant to further promote transparency, according to the county’s website.

A separate, independent auditor now handles investigations into police shootings and other uses of force. Both the panel and auditor position were established based on a commission’s recommendations following the death of Geer.

“Police work has traditionally been something shaded in a little bit of mystery, and that’s changing, and we need to change with that,” Pang said as the media academy wrapped up. “I think if the public understands the police department and understands why they do what they do, then they will trust their department is doing the right thing.”