In 1929, German World War I veteran Erich Maria Remarque penned the landmark novel “All Quiet on the Western Front,” about the futility of war.

In 1930, Hollywood filmmaker Lewis Milestone turned it into the first Best Picture Oscar winner of the talkie era and still one of the best World War I movies ever made, rivaling “Sergeant York” (1941), “Paths of Glory” (1957), “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962) and “1917” (2019).

This Veterans Day, you can watch the remake of “All Quiet on the Western Front” which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and hit Netflix on Oct. 28 as Germany’s official submission for Best International Feature at the next Academy Awards.

Forget that it’s produced by the former “opposing side.” German filmmakers have made masterful war flicks, from Wolfgang Petersen’s “Das Boot” (1981) to Oliver Hirschbiegel’s “Downfall” (2004). Nearly a century later, our old battle lines fade to reveal a humanistic portrait that reminds us that war is mankind’s worst addiction as the War in Ukraine rages.

Set in the closing days of World War I in the spring of 1917, the film follows German soldier Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer), who enlists in the German Army with his friends Albert Kropp, Franz Müller and Ludwig Behm. Their starry-eyed vision of war heroism is shattered when they’re deployed to the trenches of the western front in Northern France.

Amid the horrors of war, Bäumer forges a bond with an older solider, Stanislaus “Kat” Katczinsky (Albrecht Schuch), who helps him steal a yummy goose from a farm and asks to read him a letter from his wife (the film’s best scene). We’re told that he’s illiterate, but it also might be too hard to read, as he wonders how he’ll ever reintegrate into civilian society.

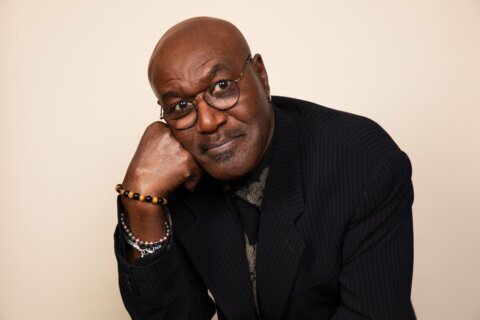

The chaos of bloody trench warfare, fiery flame throwers and gas-mask hazes is intercut with the stillness of a parallel story of peace-seeking German official Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl, the great actor from “Good Bye Lenin,” “Inglorious Basterds” and “Rush”), who meets with the German High Command to urge armistice talks with the Allied forces.

Right from the jump, we know we’re in the hand of a strong filmmaker as director Edward Berger opens with extreme wideshots of the beautiful French countryside, gazing up to the tree tops like “The Tree of Life” (2011) or “The Revenant” (2015). An overhead shot reveals dead bodies strewn across the field before an abrupt cut immerses us in the violence.

The most horrific sequence shows no gore at all. It’s a montage showing the tattered clothing of dead soldiers being matter-of-factly bagged up, mended on sewing machines like an assembly line, then shipped off for a new crop of naive soldiers to wear in battle. Along the way, composer Volker Bertelmann blares three ominous notes that set the tone.

The titular quiet is a tool for Berger, who juxtaposes the loud, chaotic violence of each attack with the calm carnage of mud and blood caked on faces in the aftermath. Roaring gunfire in the trenches cuts to German High Command hearing faint gunfire in the distance, showing that those who send kids into war often have no skin in the game.

The one symbolic light in the darkness is the peacemaking Brühl, who rides a train that appears as a small glow in the distance, like a star shining in an empty galaxy, only to gradually become larger as the headlight of a train races toward the camera on the tracks.

Just as Milestone burned images into our brain like a hand reaching for a butterfly only to fall limp to the sound of gunfire, Berger mines similar power from the sight of cracked spectacles on the ground of a muddy trench. Curiously, he doesn’t recreate the iconic butterfly image, but perhaps that’s just a filmmaker determined to chart his own path.

A scene of two “enemies” trapped in a foxhole together is just as effective, though my memory recalls the 1930 scene lasting longer. Either way, the closing statistics horrify us: “More than 3 million soldiers died here, often while fighting to gain only a few hundred meters of ground. Almost 17 million people lost their lives in the First World War.”

Nearly a century later, we still haven’t learned our lesson.