If you drive past Nationals Park down South Capitol Street, you’ll cross over the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge into Anacostia. There, you’ll find a neighborhood that’s been transformed by gentrification, erasing rich history and pushing out longtime residents.

The history is chronicled in the new documentary “Barry Farm: Community, Land & Justice in Washington D.C.,“ which screens for free Thursday from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s Just Economy Club at 740 15th Street, Northwest.

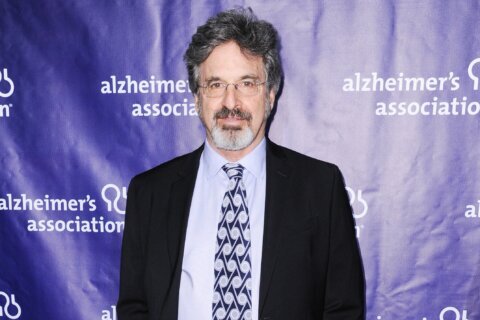

“Right now in D.C., we have a situation where a lot of people have arrived in the last couple years and a lot of stuff looks like it was built in the last couple years; that is a prescription for losing a lot of history quickly,” Co-Director Samuel George told WTOP. “To show this rich history, we start way back in the beginning and walk all the way up to the present.”

The 50-minute film covers a lot of ground in a little time, divided into seven chapters.

“Chapter 1: A Guy Named Barry” tells the history of the land’s former plantation owner.

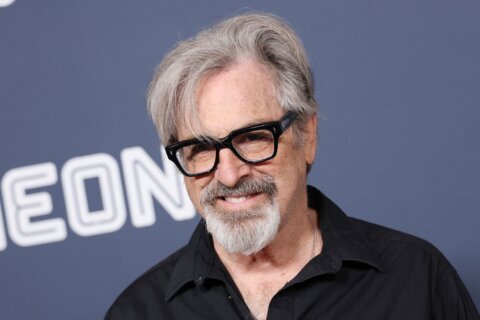

“Mr. Barry owned property in Montgomery County and enslaved people in D.C.,” Co-Director Sabiyha Prince told WTOP. “It lets us know that we’re walking around in this modern-world city and at some point there were Indigenous people here and at another point there were enslaved Africans who had a lot to do with the development of the city.”

“Chapter 2: Pearl in the Storm” recounts a group of slaves’ harrowing escape attempt led by Emily Edmondson, whose descendant is interviewed in the film today at The Wharf.

“It’s truly a riveting story,” Prince said. “It’s the story of The Pearl, a schooner that left out of The Wharf down there in Southwest with 75 or so enslaved people trying to get to freedom. They were apprehended unfortunately, but one of the people that we focus on is Emily Edmondson, who ultimately lived there on that property there on Barry’s Farm.”

“Chapter 3: The Barry Farm Dwellings” shows a vibrant side to the projects as kids shoot marbles and play baseball in the street, while the adults dance to record players.

“That public housing complex has a reputation in this city,” George said. “To actually go back and talk to the folks who lived there over the decades and find how important that was for people, what a touchstone it was for their lives, and what a strong community it was, how tight-knit it was, it wasn’t just about the land, it was about the community there.”

“Chapter 4: A Power Within” explores the neighborhood during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s as Barry Farm residents challenge D.C. segregation laws.

“They were still dealing with a lot of racism,” Prince said. “That’s the quintessential African American story, being confronted with all these different challenges. … People organizing, people being tired, the beautiful story of Etta Mae Horn being exhausted and coming to the conclusion that, yes, we’re low-income, working poor people and we deserve respect.”

“Chapter 5: Heartbeat of a City” shows Barry Farm evolving into the 1970s and 1980s with the explosion of go-go bands like the Junk Yard Band drumming on curbside buckets.

“Go-go is one of the most magic things that D.C. has,” George said. “It’s this incredible music that’s a pure invention of this city. Barry Farm was like a Madison Square Garden or a very important theater for this music, because some of the most important bands like Junk Yard Band came from there. … There was a special energy at a Barry Farm show.”

This chapter also explores the difficult dangers that emerged from cocaine to guns.

“When we talked about the ‘difficult times,’ it was important for us to have nuance and contextualize this,” George said. “Often you get into stereotypes and very easy answers that don’t explain the depth. … It’s important to talk about extreme underfunding of public housing, privatization, cuts to public services that made life for a lot of folks very difficult.”

“Chapter 6: Displacement” is the most heartbreaking as residents are forced to move. City officials swoop in and pack up one resident’s belongings before he’s even ready to leave.

“That’s the crucial bit and why we thought it was so important to tell this story,” George said. “We’re at a moment where the dwellings have been removed, except for the few that were saved, and we’re not really sure what comes next. … We’re at a moment where we risk losing this tremendous history that we really wanted to tell in this documentary.”

Finally, “Chapter 7: “A Sacred Place” shows local citizens trying to get the few remaining buildings on Stevens Road designated as historic landmarks to save them from demolition.

“There’s some hope,” Prince said. “I’m grateful to be a part of a group of people who came together over the course of many months to make this landmark case a reality. That’s organizing at its best. People from all walks of life, all different classes and backgrounds came together. … All of this energy led to the formation of the D.C. Legacy Project.”

It’s not just Barry Farm — the fight continues in other neighborhoods across the city.

“We have folks living in Greenleaf in Southwest, Park Morton in Northwest, there’s still communities fighting to not have their properties demolished,” Prince said. “Gentrification and redevelopment is sweeping in a way that’s so rapid, it’s like wildfire. … We all know that progress has to occur, but are we going to attend to the most vulnerable among us?”

You can do your part by attending the screening at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s Just Economy Club on Thursday night. It’s the film’s latest screening after last month’s showing at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Northwest.

“It’s incredibly heartening to see the reaction,” George said. “It was very positively received and so wonderful to see folks from the community feeling like their story was being told. … You’d hear people audibly agreeing with what they were seeing on screen.”

“I’ve gotten a lot of feedback from people saying, ‘Thank you for telling this story,'” Prince said. “It’s only a 50-minute doc! We could do a documentary on each chapter. … I’m a native Washingtonian and I often think about how rich our local history is. If they would have just shared that with us, I think more of us would have done better in social studies.”

Listen to our full conversation here.