He’s spliced together images for the biggest movies of our time, from superhero action in “The Dark Knight” to science-fiction dreams in “Inception” to gritty warfare in “Dunkirk.”

Now, just in time for “1917” to hit digital on Tuesday, WTOP caught up with Oscar-winning editor Lee Smith to break down his career cutting for Christopher Nolan and Sam Mendes.

“You get a little less anonymous around award season, but for the majority of the time, you can be quite happily anonymous,” Smith told WTOP. “Although, I do get the person walk up to me now and say, ‘Wow, I follow all your movies!’ I’m always shocked.”

Born in Sydney, Australia in 1960, Smith grew up watching the great Hollywood epics.

“I remember my parents taking me to cinemas to see films like ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’ … ‘Battle of Britain’ and ‘Lawrence of Arabia,'” Smith said. “I [also] really loved ‘2001.’”

That means he witnessed Anne Coates’ cut from match to sunrise in “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962) and Ray Lovejoy’s cut from bone to satellite in “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968).

“I think we’re the sum of everything that’s happened before,” Smith said. “They’re all embedded deep in my subconscious. … I have a pretty good memory for films. … I can see something 20 years ago like I saw it yesterday. … So I could be an idiot savant.”

His passion was fueled by his father, an optical effects supervisor in the film industry.

“I had another in-road … although he was in the commercial world not features,” Smith said. “My main job was making tea and sweeping around the place, but that’s the way to learn. You start at the bottom.”

He worked his way up not as an editor but as a sound designer for Holly Hunter in Jane Campion’s “The Piano” (1993) and Jim Carrey in Peter Weir’s “The Truman Show” (1998).

“I concentrated on sound for the first part of my career, then I did a transitional thing where I was working quite a lot with Peter Weir’s films as like a junior editor. Then I would be the sound supervisor or sound designer on his films, then eventually I became his editor.”

He said his sound editing background is very informative to his job of film editing.

“Sound is an incredible way to control people’s emotions and pace and rhythm,” Smith said. “It’s amazing what you can do subtly and subliminally. … I have an enormous sound library in my picture-editing [software] Avid that I draw on continuously as I’m cutting.”

After his work with Weir, he formed a long collaboration with Nolan on the trilogy of “Batman Begins” (2005), “The Dark Knight” (2008) and “The Dark Knight Rises” (2012).

This allowed him to edit the Oscar-winning performance of Heath Ledger, whom Smith got to know “reasonably well” after editing his early Australian film “Two Hands” (1999).

“I saw him several times during the shoot of ‘The Dark Knight’ on the set and it was always hugely amusing,” Smith said. “Right from the first day of shooting, I was just completely in awe of how far he’d come from doing a low-budget film in Australia to standing there with his back to camera holding onto that mask as he commands the screen.”

He’ll never forget watching the dailies come in of Ledger’s performance.

“I was sitting in a small trailer on location with Chris Nolan, the cinematographer and everybody else and we’re just all sitting there going, ‘Oh, man, this guy’s amazing,’ just the way he walks, the way he talks. He brought everything to that role.”

Sadly, Ledger died during post-production, meaning Smith watched footage of a ghost.

“It was terribly sad,” Smith said. “We were about 10 or 12 weeks past the end of the shoot. It’s of course incredibly sad when anyone passes away, but he was such a brilliant actor and he brought so much to that role. … It was a great loss that he’s no longer with us.”

After “The Dark Knight,” Smith reunited with Nolan on the sci-fi masterpiece “Inception” (2010), cutting together the “dreams within dreams” without confusing the audience.

“That is the challenge,” Smith said. “Chris does make very complicated films and I think my job in the whole process is to try to keep it as understandable as you can, because there’s nothing worse than a film where the audience gets lost to the point of being disappointed.”

“The secret that we were always trying to do with Chris’ films, ‘Inception,’ ‘Interstellar,’ and ‘The Prestige,’ was being faithful to Chris’s original idea … but never getting into a point where you’d be sitting there as an audience member feeling that you’ve been left out.”

Test screenings proved vital to see if audiences grasp the intricacies.

“Those movies are very finely tuned,” Smith said. “Some people get them to great minute detail. Other people misunderstand them completely, but they still love them.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge was “Dunkirk” (2017), as Smith had to edit three intercutting timelines: a week on land, a day at sea and an hour in the air during World War II.

“There was an enormous amount of cross cutting,” Smith said. “We did do a lot of jigging around with the aerial stuff. … We had to move that around, add and subtract where it came in, so the audience … wasn’t completely perplexed.”

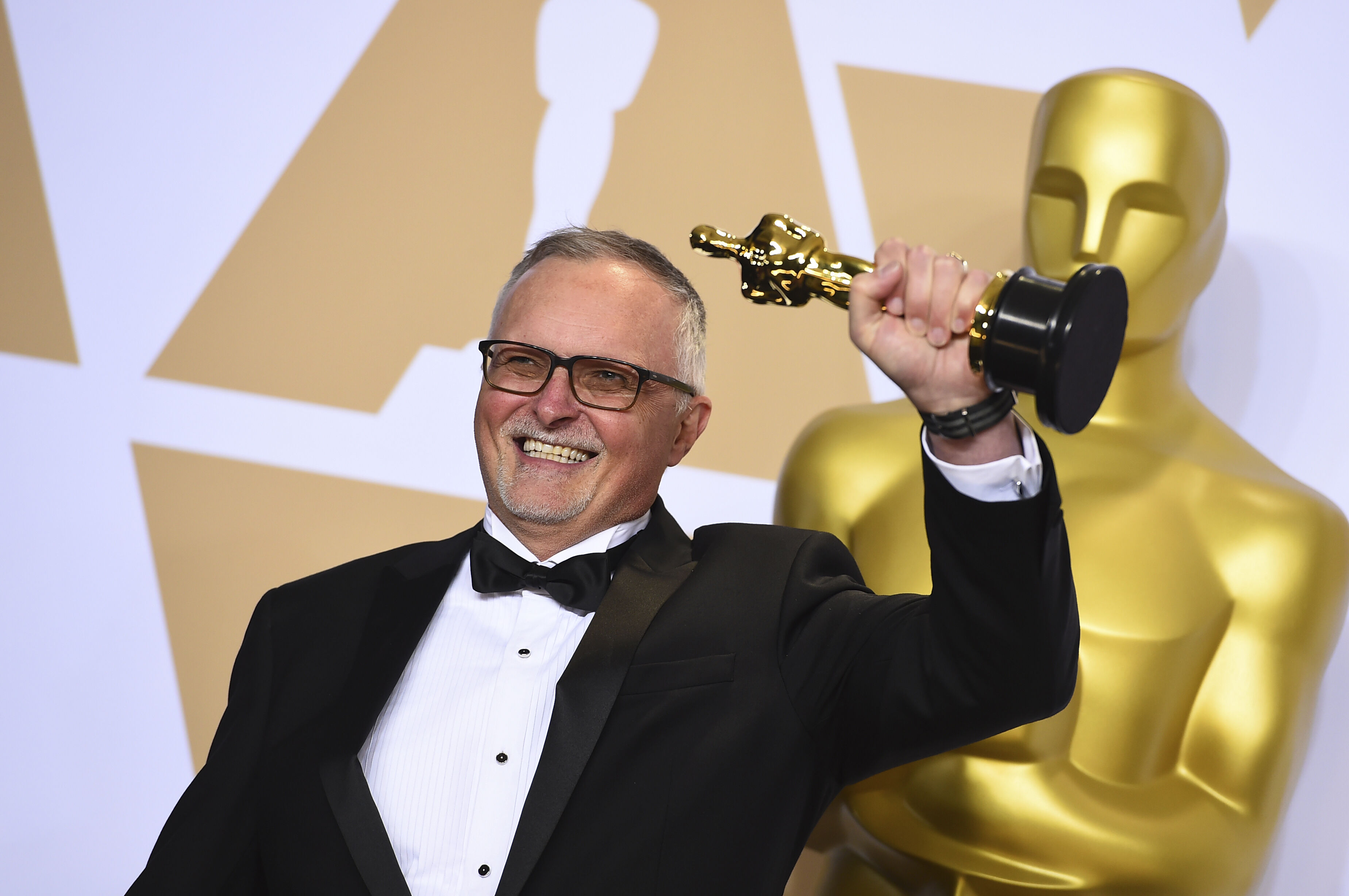

For his efforts, Smith won the Academy Award for Best Film Editing, receiving the award on stage from his former “Interstellar” colleague Matthew McConaughey.

Most recently, he worked on Mendes’ World War I epic “1917” (2019), which was edited to appear as if one continuous shot when really it was several long takes stitched together.

“Sam and I agreed we’d never divulge how many cuts there actually are,” Smith said. “We didn’t know 100 percent that this was going to work, [so] some of those joins were very hair raising. … There’s a lot of monkey business in that movie. That’s all I can tell you!”