WASHINGTON — The final frontier of space has proven fertile ground for phenomenal fiction filmmaking in recent years, from Alfonso Cuaron’s masterful “Gravity” (2013) to Christopher Nolan’s imaginative “Interstellar” (2014) to Ridley Scott’s entertaining “The Martian” (2015).

And yet, it’s always refreshing when Hollywood nails a true story of NASA heroics, be it “The Right Stuff” (1983), “Apollo 13” (1995) or “Hidden Figures” (2016). If ever there was a moment deserving of the big-screen treatment, it was the moon landing on July 20, 1969, reminding us of a period in American history when brave men and women dared to reach for the stars.

Enter Mr. City of Stars himself, Damien Chazelle, who follows his Best Director Oscar for “La La Land” (2016) by sending Ryan Gosling floating further up into the stars as Neil Armstrong in “First Man.” Ladies and gents, Chazelle has done it again, delivering one of the finest space films ever made by focusing on the everyday humanism of our reluctant heroes rather than flag-waving cliches, thus cementing his place on the forefront of the next frontier of cinema.

Adapted by Josh Singer (“Spotlight”) from James Hansen’s 2005 biography of the same name, the film patiently chronicles the entire decade leading up to the landing. It opens with a young Armstrong flying an X-15 aircraft over the Mojave Desert in 1961, followed by the successful Gemini 8 docking mission in 1966, the tragic Apollo 1 catastrophe in 1967 and ultimately Armstrong stepping onto the lunar surface as the first man on the moon in 1969.

Gosling is well-suited as the quietly handsome hero with a military haircut, presented far more reserved than Tom Hanks’ likable Jim Lovell, but just as fascinating a character study. Gosling plays the role with an emotional distance authentic of suburban dads in the 1960s, especially one scarred by the Korean War and his daughter’s death. Children are supposed to bury their parents, not the other way around, so the hero’s somber detachment is justified.

The burden also weighs on his wife Janet, portrayed by Claire Foy (“The Crown”), who is entirely realistic as a mom dealing with rowdy kids. Rather than a passive worrying wife, she takes action to demand that mission control turn her space monitor back on. Best of all, she confronts her husband the night before the mission, forcing him to tell his kids the truth: that he might not return. Watch her eyes in this scene. Dark seas of tranquility suddenly erupting.

Surrounding them is a stellar supporting cast: Corey Stoll (“House of Cards”) as Buzz Aldrin, Lukas Haas (“Witness”) as Michael Collins, Jason Clarke (“Zero Dark Thirty”) as Ed White, Kyle Chandler (“Argo”) as Deke Slayton, Brian d’Arcy James (“Spotlight”) as Joseph Walker, and Pablo Schreiber (“13 Hours”) as Jim Lovell. This revolving door of beloved and ill-fated NASA heroes drives home the human sacrifice necessary for the ultimate battle of man vs. nature.

It’s this theme that Chazelle nails so brilliantly right from the opening sequence, mining slow-burn suspense from an airplane intro like Chuck Yeager’s historic flight in “The Right Stuff.” Working with favorite cinematographer Linus Sandgren (“La La Land”) and editor Tom Cross (“Whiplash”), Chazelle presents a trio of close-ups of the aircraft, a three-beat salvo that has become one of his auteur trademarks, be it instruments in “Whiplash” or vinyl in “La La Land.”

As the space training begins, Chazelle employs the cinema verite of cockpit shaky cams for maximum realism, both during a “vomit comet” simulator and the actual Gemini 8 flight. Here, Armstrong breathes a sigh of relief after successfully docking before suddenly tumbling out of control with whooshing sound design each time the vessel whips around. This same false sense of security precedes the ill-fated Apollo 1 team, who burn alive in a simulation.

Such tragic mistakes coincide with footage of Soviet achievements, causing NASA astronauts to become frustrated yet motivated during the Space Race. The loss of life also fuels protests over the space program’s cost — in blood and treasure — underlined by the Civil Rights Movement where a protester reads Gil Scott-Heron’s poem “Whitey On the Moon.” At one point, NASA officials say, “Is it worth the cost?” Armstrong replies, “It’s a little late to ask that.”

It all builds to the eve of the big moonshot, as viewers lean forward on the edge of their seats for a majestic blastoff that gives way to transcendent space imagery. As the ship disappears into the darkness of a classical waltz, we’re reminded of Stanley Kubrick’s use of the “Blue Danube Waltz” in “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968). You might even notice a hint of Mia & Sebastian’s Theme from “La La Land,” an echo by Oscar-winning composer Justin Hurwitz.

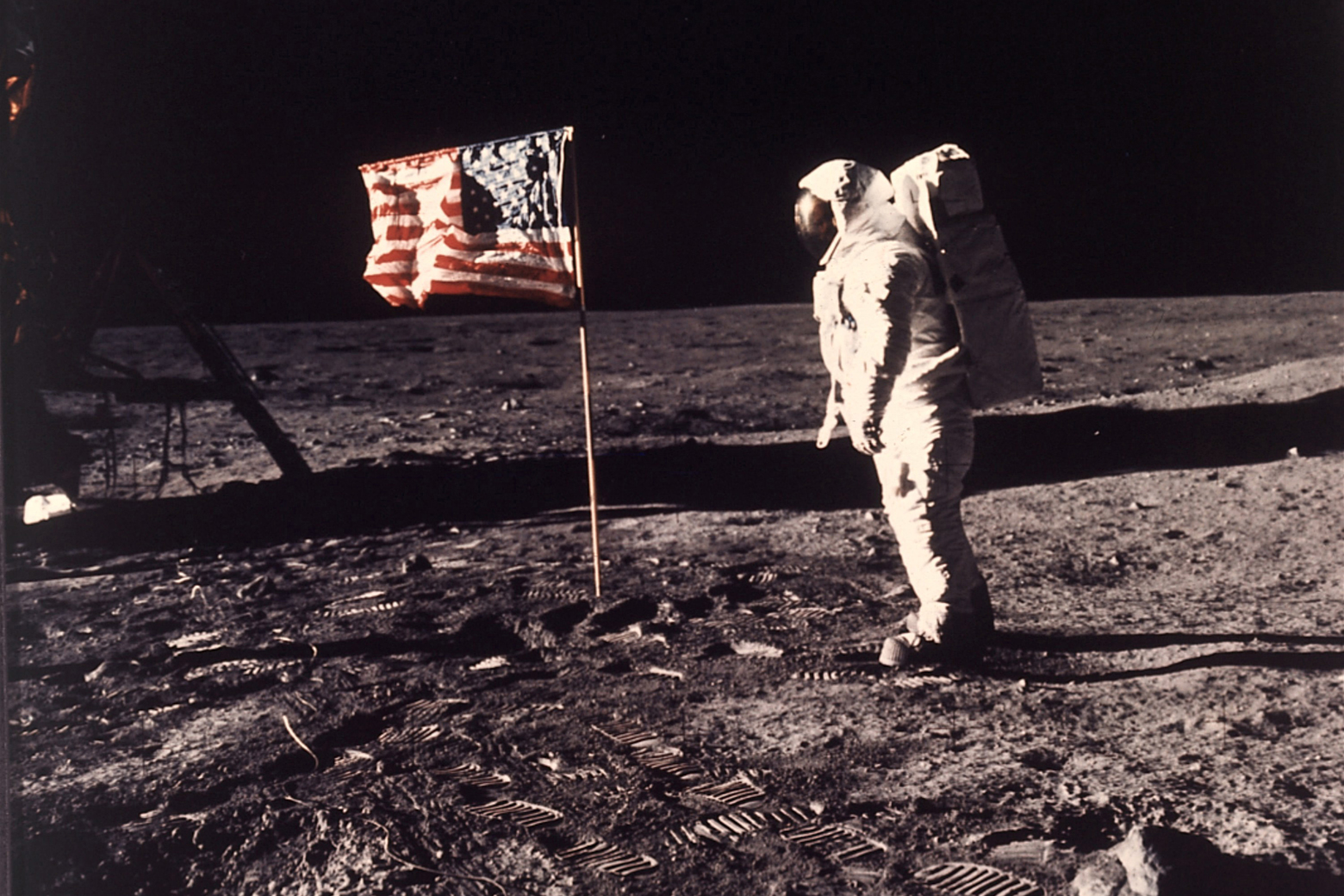

Which brings us to the moment everyone has been waiting for: “The Eagle has landed.” As Gosling forms a footprint on the lunar surface and delivers the famous line — “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind” — it miraculously doesn’t feel staged, but rather organic to the film we’ve been watching all along, drawing claps from the audience.

The hero just stuck the landing, but will the movie? Naysayers argue that the film doesn’t sufficiently highlight the American flag planting, suggesting a globalist bias over nationalist achievement. Ironically, many of these concerns are ginned up by Twitter trolls who haven’t even seen the movie, hypocritically urging Space Race patriotism while supporting a White House bowing to Moscow in a way that Ronald Reagan never would. Can’t have it both ways.

“To address the question of whether this was a political statement, the answer is no,” Chazelle said. “I wanted the primary focus in that scene to be on Neil’s solitary moments.”

Having seen the film, I can happily report that this controversy is overblown. We do, in fact, see the stars and stripes on the moon, but rather than swell the music for a giant close-up, Chazelle makes the artistic choice to instead focus on a more intimate moment as the hero overcomes his grief. The result is far more powerful, guaranteed to bring tear to your eye.

Moreover, it’s a tonally consistent culmination of what the movie is really all about. Every great movie is about one thing on the surface (moon landing) and another thing underneath (the death of his daughter). Armstrong’s reflective moment on the moon is the resolution to previous flashbacks of him stroking his daughter’s hair, imagining her alive on a swing set, and walking into the shadows of his back porch as if it were the dark side of the moon.

The final shot is equally powerful, as Armstrong and his wife stand on opposite sides of NASA quarantine glass like the end of Wim Wenders’ “Paris, Texas” (1984). As their hands reach up to the glass, finally connected, Chazelle cuts to black at just the right moment: when the characters’ inner journey is resolved. No need for text graphics explaining what happened to them afterward. No need to stick around any longer. It’s time to go: artful, nuanced, perfect.

Chazelle just dared to make an intimate film about a monumental achievement, not because it would be easy, but precisely because it would be hard, as JFK so eloquently said. The result is a unique masterpiece that’s one small step for man and one giant leap for the movies.