WASHINGTON — Few things in recorded history can rival the majesty and tragedy of the Titanic, the “unsinkable” ocean liner that crashed into an iceberg and sank during its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City on April 15, 1912, killing 1,503 people.

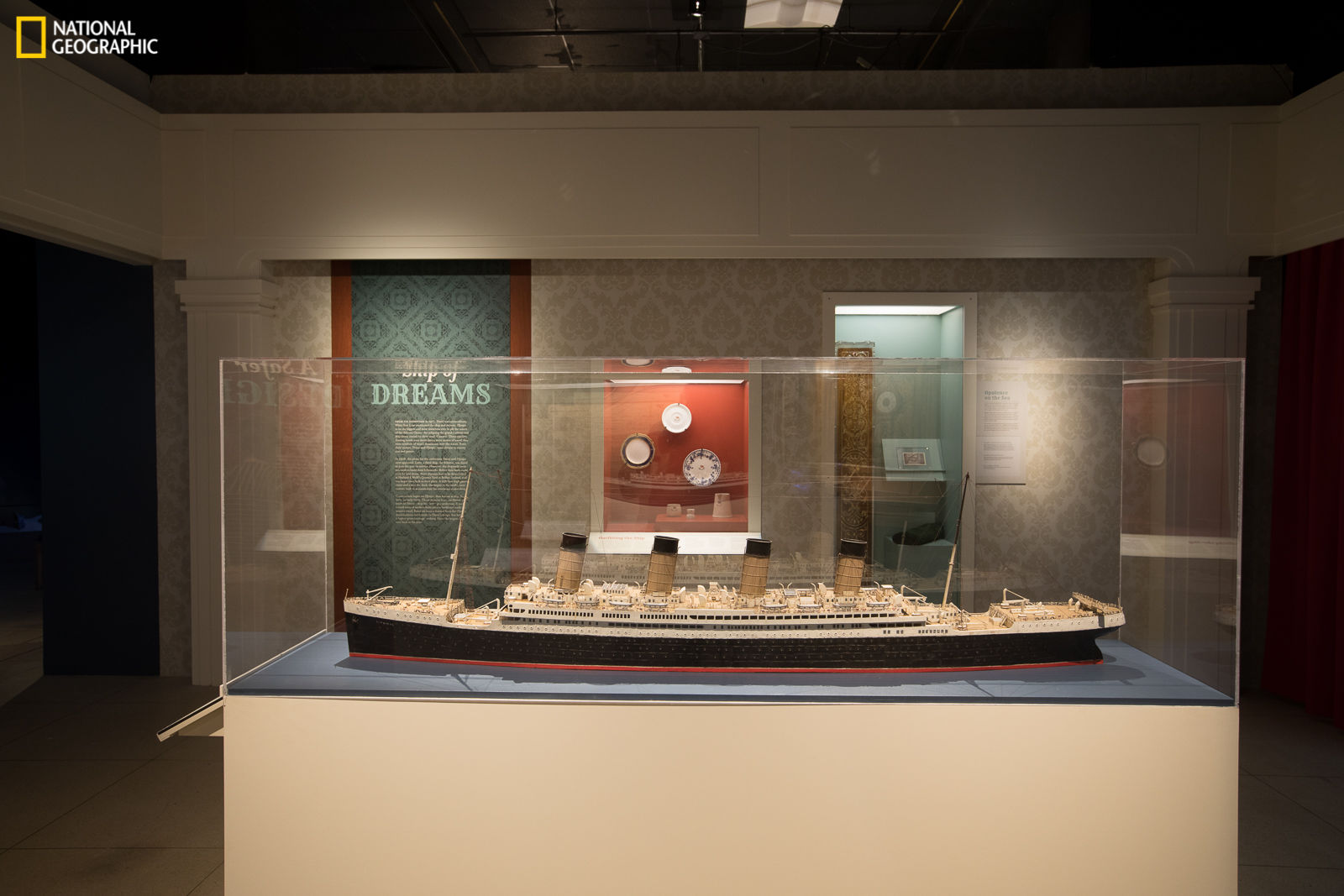

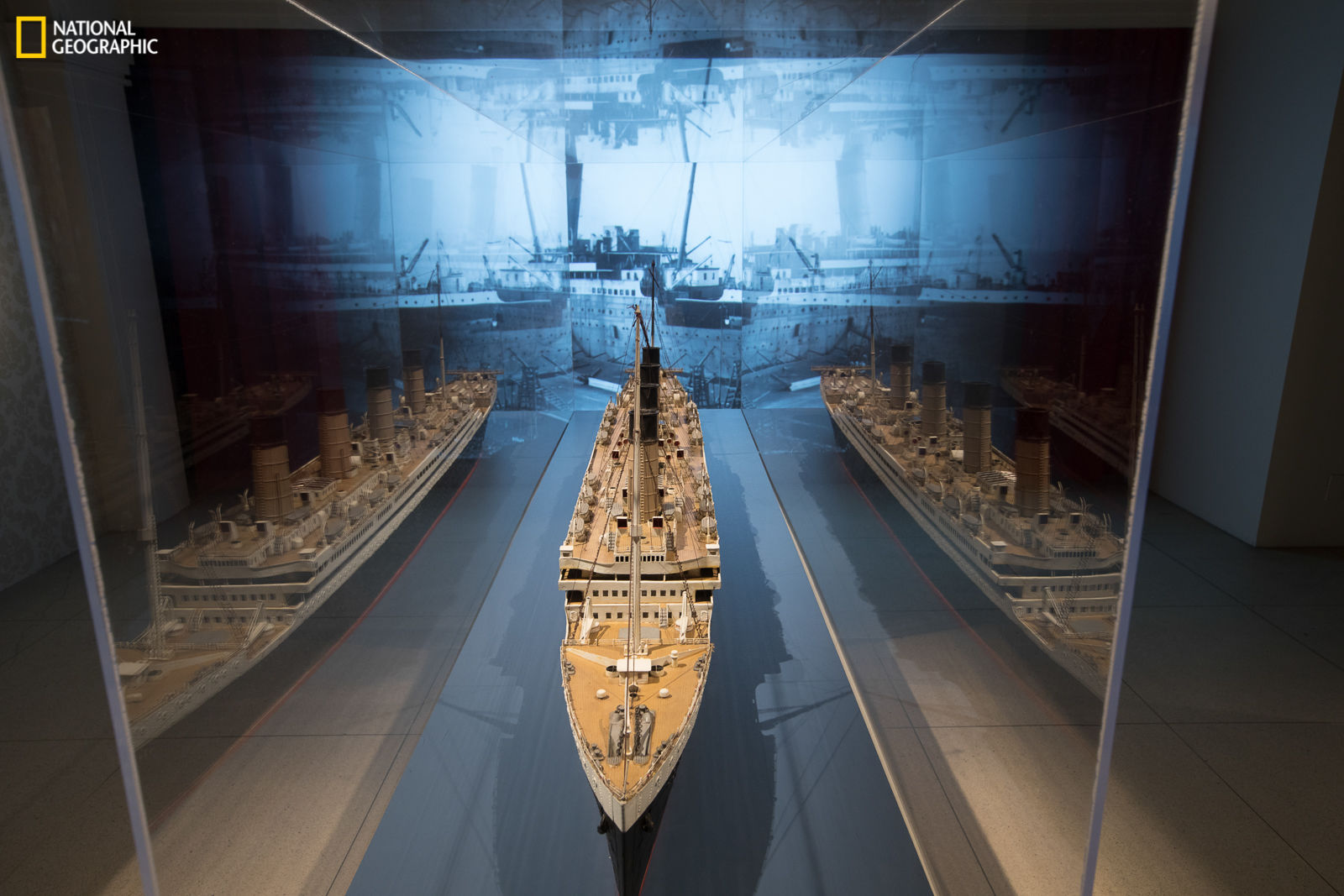

Now you can see a rare collection of real-life artifacts recovered from the ship, as well as memorable movie props from James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster at the new exhibit “Titanic: The Untold Story,” showing at the National Geographic Museum in D.C. through Jan. 6, 2019.

“You think you know the story, but if you come to this exhibition, you’ll learn that there are still new chapters of this story that are continuing to unfold,” National Geographic vice president of exhibitions Kathryn Keane told WTOP. “We are the only East Coast venue for this exhibition and it’s a wonderful opportunity to learn some stories you didn’t know before.”

Namely, you’ll learn how the Cold War inspired the discovery of the Titanic wreckage.

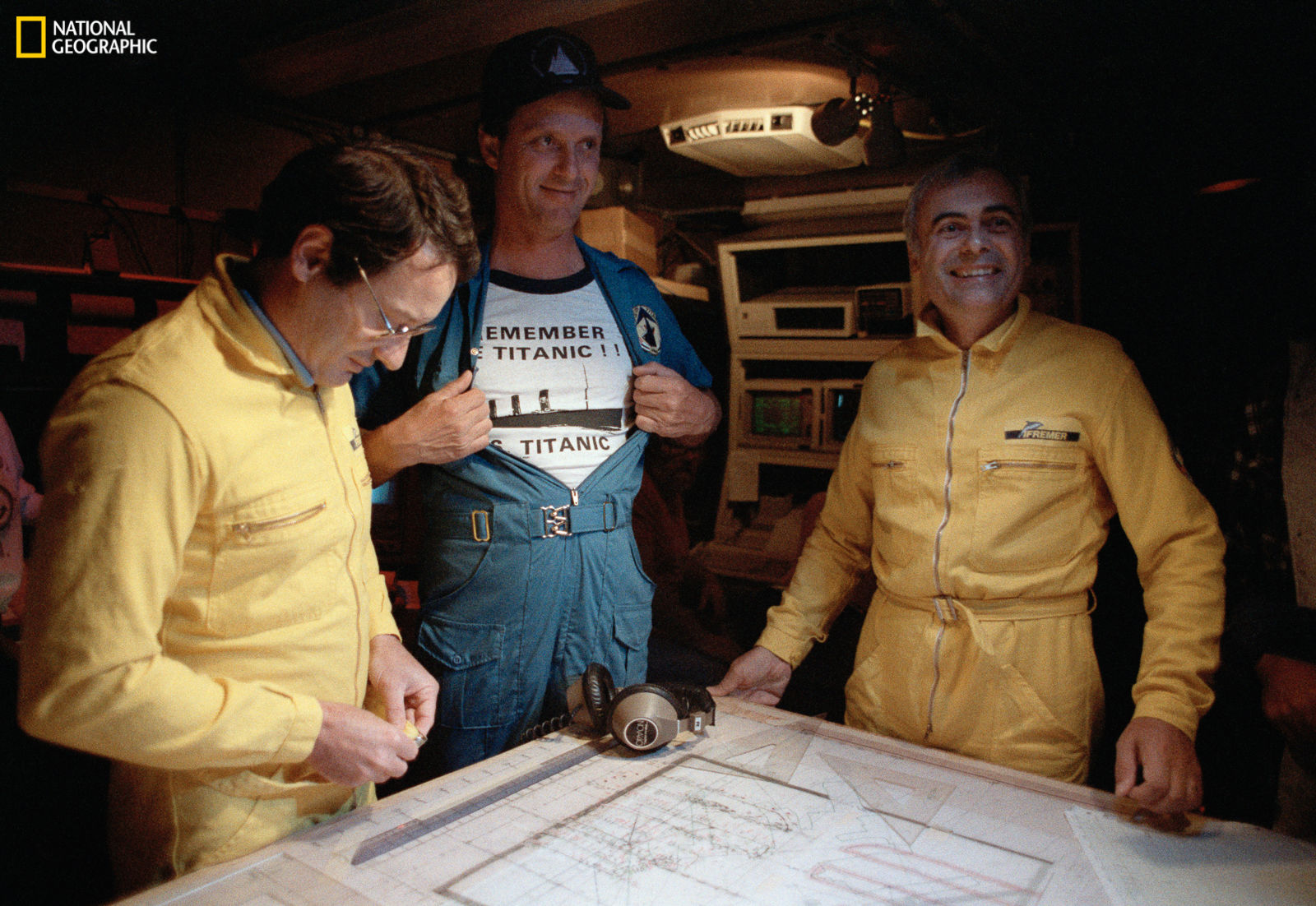

“When Bob Ballard discovered the Titanic in 1985, he was actually on a classified mission for the U.S. Navy to document two sunken ’60s-era submarines,” Keane said. “These were U.S. submarines that were lost in 1963 and 1968, the USS Scorpion and the USS Thresher, the biggest losses to the U.S. Navy since World War II. Both had nuclear reactors on board.”

As a famous underwater explorer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Ballard was obsessed with finding the Titanic, so he struck a secret deal with the U.S. government.

“[He] had all of the technology needed to document these ships,” Keane said. “There was really only one thing he wanted to do, which was to use the Navy’s resources to go look for the Titanic. … After his classified mission was complete, he had 12 days [left]. … Bob had a great poker face, did his work for the Navy, and then went off to find the Titanic. They had four days left when they were able to discover, by the tracing of the debris field, the Titanic.”

Turns out, the Titanic was situated directly between the two sunken submarines.

“The Thresher was off the coast of Nova Scotia, the Scorpion was near the Azores, and Titanic was right in the middle,” Keane said. “I don’t think the Navy secretary was overjoyed when he got the call from Bob saying, ‘Hey, guess what? I found the Titanic!’ They really didn’t want the cover story to be blown, but it was such a big deal that we couldn’t not report it.”

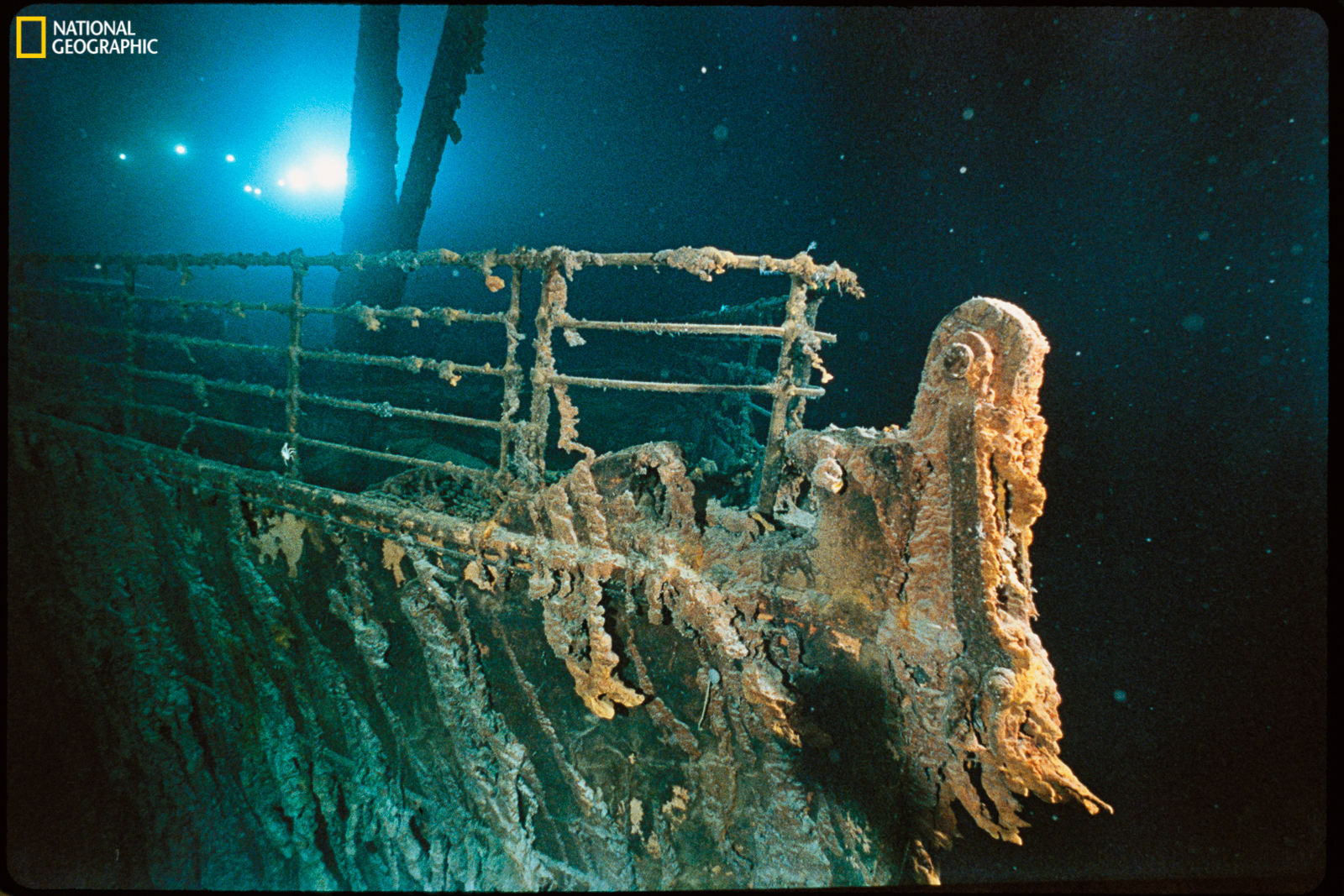

Now, after subsequent submersible visits, Nat Geo is displaying rare items and photographs.

“The exhibition is divided into three parts,” Keane said. “[First], we talk about the cover story and classified mission. … The second part is really about the technologies … to send robots to the deepest depths of the ocean to do what humans could not do. … And the third part is about the ship itself. We profile some of the survivors, some of the personalities, and we have artifacts taken off the ship by survivors or passed down through generations of families.”

You’ll get goose bumps standing just inches away from the chilling artifacts.

“We have two deck chairs, one from the Titanic [and] one from the Carpathia, which came to the rescue,” Keane said. “Wallace Hartley was head of the eight-person orchestra, [which] was playing until the very end. He did not survive the sinking, but the music pouch that he carried all of his sheet music was recovered from his body, along with all of the sheet music.”

You’ll also find the belongings of J.J. Astor and his 18-year-old pregnant wife Madeleine.

“J.J. Astor was the wealthiest man on the ship,” Keane said. “He did not survive; she did. … We have her life jacket and his pocket watch … exhibiting them together for the first time.”

As for the “unsinkable” Molly Brown, you’ll see what was in her pocket that fateful night.

“She was a loud voice of reason during the chaos,” Keane said. “She was the one who convinced the lifeboat captain to turn around and go back. They had excess capacity on their boats. … She was carrying in her pocket a little Egyptian statue, called an ‘ushabti.’ She had been in Egypt buying art and antiquities for the Denver Art Museum. … She ended up giving that little statue to the captain of the Carpathia as a thank you for rescuing them.”

Molly Brown was, of course, made famous by actress Kathy Bates in the 1997 movie “Titanic,” from which the museum is displaying numerous props, costumes and entire Hollywood sets.

“We have incredible props from the 1997 blockbuster, which we borrowed from the 20th Century Fox archives. James Cameron did a wonderful job of recreating the sets as accurately as possible. … We’ve got the first-class suite, Rose’s suite, [site of] the famous drawing; the couch is there! We have the Marconi Room, the radio room where the S.O.S. signals went out. … We’ve got that great third-class bunk set where Leonardo DiCaprio spent the one night.”

You’ll also see the costumes worn by the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet.

“We’ve got some wonderful costumes,” Keane said. “Costumes are always fun to see. We’ve included Captain Smith’s costume, one of Rose’s ball gowns that she wore on this incredible ship, then we have the one costume that you see Jack Dawson in throughout the entire film.”

Why are folks still fascinated by Titanic more than a century later?

“The greatest example of technological achievement, the biggest, best, most luxurious ship, and yet when up against mother nature, it still wasn’t enough,” Keane said. “There were stories of heroism and survival, people that survived, laws that were changed, lessons that were learned, and great discovery if you think of the century since, all of the science and expeditions. … It’s the classic story of tragedy, survival, class divides, man vs. nature, all of those things rolled into what we are now remembering as the greatest shipwreck of all time.”

Find more details on the museum website. Hear our full conversation with Kathryn Keane below: