WASHINGTON — He played Jackie Robinson in “42” and James Brown in “Get on Up.”

This Friday, Chadwick Boseman takes on another icon in “Marshall,” playing a young Thurgood Marshall in a case decades before making history as the first black Supreme Court justice.

The film follows Marshall’s 1940 journey to conservative Connecticut to defend a black chauffeur, Joseph Spell (Sterling K. Brown), accused in the sexual assault and attempted murder of his rich white employer, Eleanor Strubing (Kate Hudson). Marshall partners with a young Jewish lawyer, Samuel Friedman (Josh Gad), to defend Spell in an uphill battle against a racist culture that paved the way for Marshall to create the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

“He is literally the single attorney for the NAACP going around dealing with all of these cases,” Boseman said. “Later on, he had other people, he got a bigger budget, he could bring on other people, but during this period, he was literally the only person going around doing this. We’re watching one of the moments where he begins to assemble a group who can help.”

Having done multiple biopics in recent years, Boseman is experienced in playing real-life heroes, but he insists the preparation and performance is different with each new role.

“They’re all very different men, three different movies, three different conceits, three different ways of playing a real person,” Boseman said. “Brian Helgeland wanted Jackie Robinson to filter through me. … I found that the physicality was more important; I had to play baseball like him, move like him, look like him. So for me, the preparation was a very physical one.”

He took a completely different approach to playing James Brown in “Get On Up.”

“James Brown was more an imitation,” Boseman said. “You know this man’s music, what he moves like, what he sounds like, what he dresses like, the types of things he’s going to say, humor, serious. You know his police record! Know what I’m saying? So there’s certain things I had to do that would give you a sense of him, but I also didn’t want to make fun of the man.”

His latest role as Thurgood Marshall required a much different type of research.

“There’s no footage,” Boseman said. “There’s Hall of Fame footage that people have never seen of Jackie Robinson; there’s concert footage that people have never seen [of James Brown]. This one, there’s no ‘SportsCenter’ for Thurgood Marshall in a courtroom! So this was discerning and extracting from the pages, from biographies, autobiographies, articles.”

As for the look, he didn’t think his appearance needed to be identical.

“Since I don’t look like him, you don’t necessarily want to go there,” he said. “You don’t want to present the problem; you want to present: ‘How can the spirit of this man, the essence of him come through me?’ Let’s not put a fake mustache; what is my Thurgood Marshall mustache? Let’s not have a wig; what is my Thurgood Marshall hair? Let’s let him grow out of me.”

Was he surprised by anything he learned about Marshall?

“Everything,” he said. “It’s one thing to read it; it’s another thing to experience it and go, ‘He didn’t sleep tonight. He got on the train, got off and started working. He left his comfortable life during the Harlem Renaissance when he could be sitting with the greatest artists of that time, and he’s going off to risk his life selflessly.’ So the combination of attributes that you read on the page, when you actually experience them … you realize this is a heavy dude.”

His moral heft is epitomized by two key pieces of dialogue. At one point, he tells the press: “The constitution wasn’t written for us, we know that. But we’re going to make it work for us. From this day forward, we claim it as our own.” Later, when Gad asks, “Are you just going to go around putting out fires?” he replies, “It’s not fires I’m after, Sam. It’s fire itself.”

Hats off to writers Michael and Jacob Koskoff, a father-son duo mining legal experience for clever script devices, namely an eye dropper splashing doubt into a water glass for the jury.

“The great thing about this movie is that it was written by an attorney and his son,” director Reginald Hudlin said. “He heard the legend of this case where Marshall came to town and worked with a local attorney, so he did incredible research. That [eye dropper] was in the script when I got it! I’m like, ‘Aww, this is great! We’re shooting that!’ Courtroom dramas, we know that space, so to find such a powerful visual metaphor to bring that challenge to life.”

The biggest challenge was the fact that Marshall isn’t in the courtroom for some of the case’s most pivotal moments, leaving Gad to deliver final arguments while he takes the next case.

“One of the challenges of this man’s life is that for every case that he was there [in court], someone else was suffering, someone else would have a miscarriage of justice, so he had to be everywhere at once,” Hudlin said. “When you have a challenge like that, there’s two ways of doing it. One is you fudge it. You go, ‘Well, let’s just have him there. Let’s cheat history.’ But I’m like, ‘No, no, no. We’re not taking the easy way out.’ Thurgood was gone. He had to go.”

Such a challenge would undercut most screenplays with a passive protagonist, but “Marshall” finds clever ways to keep Thurgood present in his absence. During the climax, Gad’s closing argument is intercut with Marshall previously dictating the defense strategy at a train station.

“Here’s one of the greatest attorneys, one of the most eloquent speakers gagged,” Hudlin said. “So I looked at that impossible situation as a chance for us to do something really dynamic, really visual, and that really delineated his contribution to the case and to the law.”

As a director, Hudlin mostly keeps the tone light with a jazzy score that recalls Quincy Jones’ “In the Heat of the Night” (1967) or Alan Silvestri’s “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” (1988). This funky vibe is matched by throwback transitions, such as diagonal wipes, that elicit a very specific 1940s setting where African Americans faced the height of Jim Crow segregation.

Dripping with history, the film fittingly had its world premiere at Howard University on Sept. 20. As the movie reminds us, Marshall attended Howard after being banned by the University of Maryland, which he successfully sued to get the state Supreme Court to force integration.

Such history will cause Americans — especially D.C. area viewers — to leave “Marshall” feeling enlightened, as the film is as historically educational as it is narratively gripping. It’s the perfect reminder that our real heroes don’t wear superhero capes, but rather judges’ robes. Will Boseman’s superhero Black Panther inspire a new generation to research Marshall?

“I’m pretty sure it will,” Boseman said with a smile. “I’m pretty sure it will.”

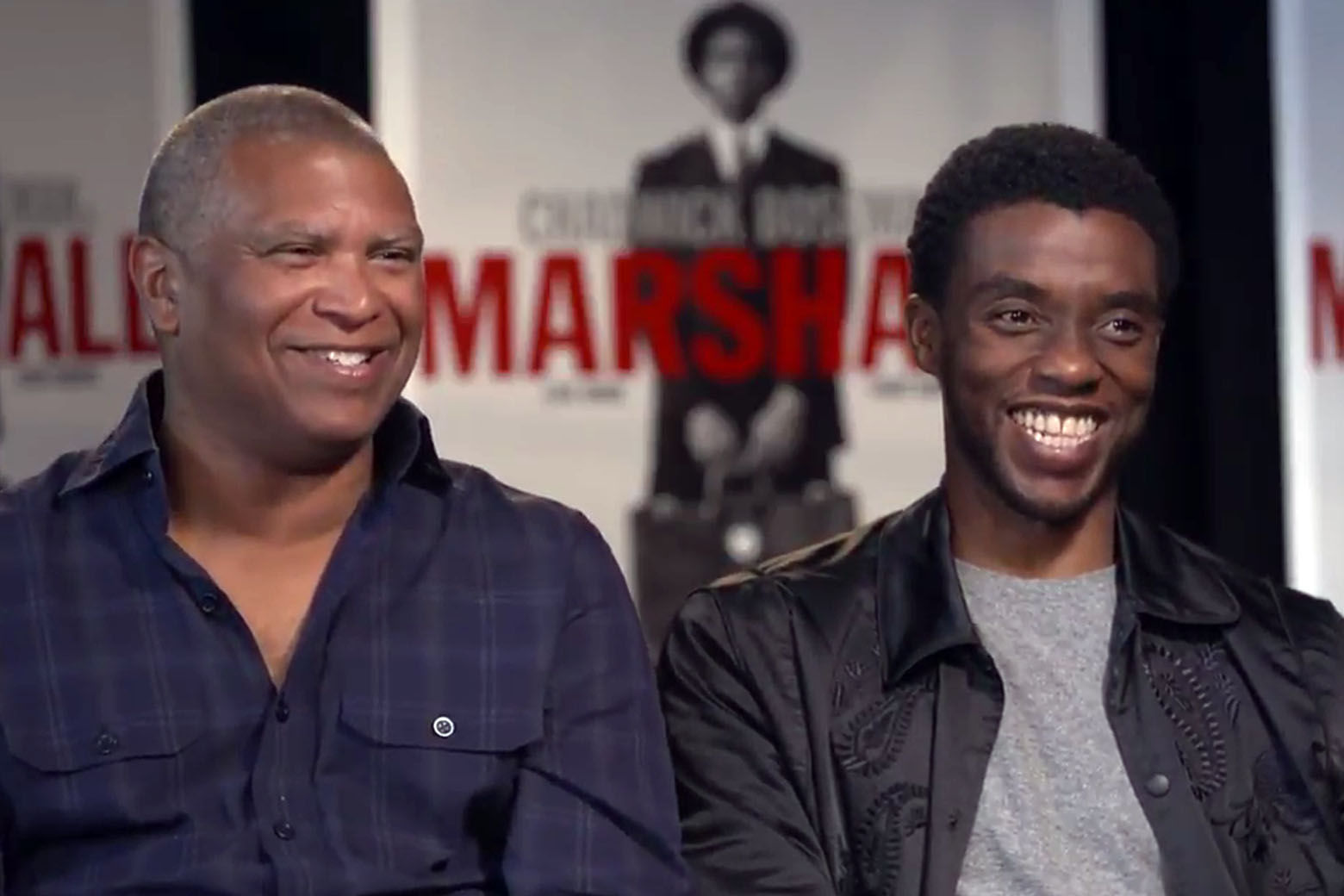

Listen to our full conversation with actor Chadwick Boseman and director Reginald Hudlin below: