WASHINGTON — Most musicians would kill to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame just once. But David Crosby has had the honor twice: once for his work with The Byrds and again for his work with Crosby, Stills and Nash.

If you’ve never seen the legend perform live — or can’t wait to see him again — this week brings the perfect chance as Crosby returns to The Birchmere at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday in Alexandria, Virginia.

“They have a great audience,” Crosby told WTOP. “It’s not really just a club. I normally don’t play clubs because they’re serving and people tend to be more rowdy. … But I do really like The Birchmere. It’s always been really good to me. Every time I’ve gone there, there was a really good audience.”

What can we expect to hear Tuesday night?

“I have two new records worth of stuff that you haven’t heard,” Crosby said. “You’ll get to hear stuff from both of them, and a ton of other stuff from The Byrds on up through CSN, CSNY, you know, all of that. I have so much material, man, I can’t even believe it. … And there’s cards you can fill out with questions at my shows. You can ask me anything, and I might even answer it in front of the audience.”

What do you even ask a musician this accomplished and a counterculture icon of this magnitude?

Born in Los Angeles in 1941, Crosby grew up surrounded by a creative family on the doorstep of Hollywood. In fact, his father was none other than Oscar-winning cinematographer Floyd Crosby.

That’s right, his dad filmed Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr kissing in the waves in “From Here to Eternity” (1953), won a Golden Globe for filming Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly in “High Noon” (1952) and won an Oscar for shooting F.W. Murnau’s “Tabu: A Story of the South Seas” (1931), not to mention John Sturges’ “Old Man and the Sea” (1958) and Roger Corman’s “House of Usher” (1960).

“It’s fun to be a little kid and get to go on movie sets with my dad,” Crosby said, nostalgically. “I was watching him make a movie before I could spell ‘movie.’ So that part is always fascinating.”

There was even a time Young David wanted to follow in his father’s filmmaking footsteps.

“I wanted to be an actor,” Crosby said. “But the truth was, as soon as I started singing, that was what I wanted to do. It was just so natural to me and was so much exactly what I loved doing.”

After briefly studying drama at Santa Barbara City College, Crosby dropped out to pursue his music career, eventually moving to New York City to hone his craft in the Greenwich Village folk scene.

“I went on the road as a folky and I wound up in Greenwich Village, ’cause that’s where that happens,” Crosby said. “When I first heard Bob [Dylan] I said, ‘What’s all this about? I can sing better than that!’ But then I started to listen to the words and I realized that’s what’s going on here. Those were very heady times. I loved being a folky, but then I ran into Roger McGuinn and wound up doing The Byrds.”

This brought Crosby back to his native Los Angeles, where he formed The Byrds with founding members Roger McGuinn (lead guitar, vocals), David Crosby (rhythm guitar, vocals), Michael Clarke (drums), Chris Hillman (bass guitar, vocals) and Gene Clark (tambourine, vocals).

“Gene had heard The Beatles and he was trying to write like that. He didn’t know any rules, so he was succeeding,” Crosby said. “He and Roger were singing these songs at The Troubadour in the bar and I just sat down next to them and started singing harmony. ‘Hmmm hmmmm.’ That worked out OK.”

Their debut album “Mr. Tambourine Man” (1965) reached No. 6 on the U.S. albums chart off the strength of its title track, which became a No. 1 single as a highly successful Dylan cover.

“As soon as he heard us playing his music electric, you could hear the gears working in his head,” Crosby recalled. “He immediately went out and got himself a band and stopped being a folky.”

While Dylan hatched his “Electric Dylan” stunt at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Crosby was busy writing Byrds songs like “Lady Friend,” “Why” and “Eight Miles High.” But it was Dylan who scrawled lyrics on a napkin for McGuinn’s “Ballad of Easy Rider,” which was featured on the film soundtrack for “Easy Rider” (1969) along with The Byrds’ transcendent, free-spirited tune “Wasn’t Born to Follow.”

But of all the great music that defined the ’60s, The Byrds’ most lasting legacy remains the No. 1 hit “Turn, Turn, Turn” (1965), offering cyclical words of wisdom: “A time to be born, a time to die, a time to plant, a time to reap, a time to kill, a time to heal, a time to laugh, a time to weep.”

“I love that one,” Crosby said. “The verses are actually out of Ecclesiastes in The Bible, and Pete Seeger is the one who put it to music and made it into a song. … Roger McGuinn brought it to us and said, ‘Hey, I wanna do this.’ … I always really liked it. I thought it was a really good sentiment.”

Crosby says the lyrics still apply to today’s global affairs.

“‘A time for peace, I swear it’s not too late,’” Crosby said, quoting the song. “We don’t have peace, as usual, and we would like to. … We need peace. We need to not be sending our kids off to war.”

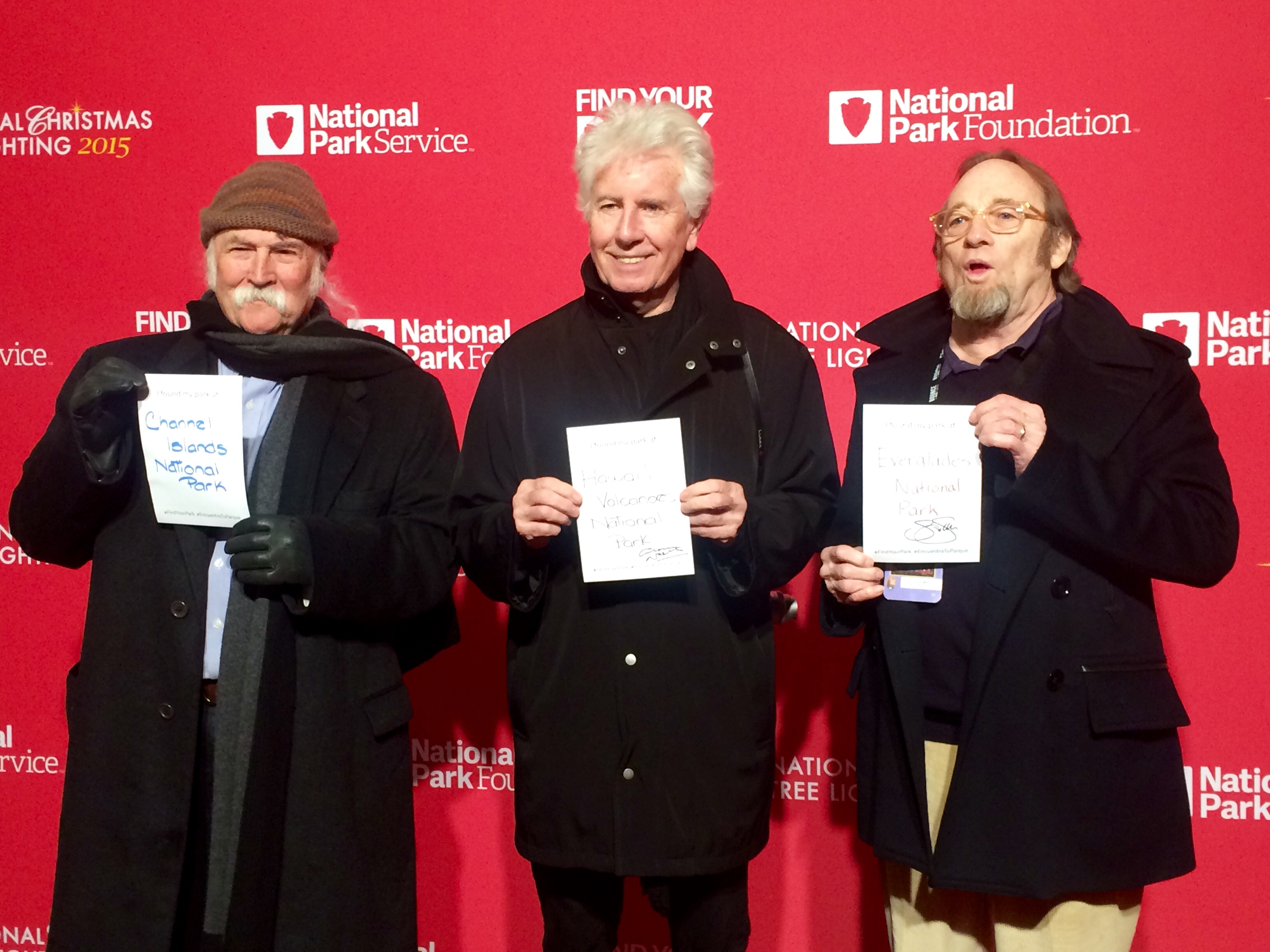

This anti-war message made Crosby a kindred spirit to Stephen Stills, who wrote “For What It’s Worth” for Buffalo Springfield. Stills was destined to unite with Crosby and Graham Nash of The Hollies to form a folk-rock supergroup at the urging of Cass Elliot of The Mamas & The Papas.

“If it wasn’t for Cass Elliot, none of this would have been happening,” Nash told WTOP. “I have a feeling she knew what the three of us would sound like singing together before we did. She knew I was unhappy with The Hollies, she knew that Springfield had broken up, she knew that Crosby & Stills were trying to get some duo action together, and I think Cass really knew what we would sound like.”

So, the trio came together for their first performance organically in Joni Mitchell’s living room.

“After Byrds and Springfield, Stephen and I started singing together and we tried it with Nash one night at Joni Mitchell’s house,” Crosby said. “It worked fantastically well.”

Joining up with occasional fourth member Neil Young, CSNY (Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young) fittingly covered Mitchell’s “Woodstock,” which played under the end credits of the 1970 documentary.

Along with “Woodstock,” the group rattled off numerous other hits, including “Wasted on the Way,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” “Ohio,” “Our House” and “Just a Song Before I Go.” Arguably their biggest hit was the cross-generational ballad “Teach Your Children,” written by Nash back when he was a member of The Hollies, but not recorded and released until the CSNY album “Déjà Vu” in 1970.

“I’ve tried to analyze the success of that song, and I just come down to the fact that throughout the world as I travel, I realize that people want the same thing,” Nash told WTOP. “They want a better future for their children, and with that human desire for a better world for their kids, I think ‘Teach Your Children’ kind of taps into that, and I think that’s why it’s so popular.”

As for Crosby, he wrote tunes for both incarnations, including CSN’s “Guinnevere,” “Wooden Ships,” “Shadow Captain” and “In My Dreams,” as well as CSNY’s “Almost Cut My Hair” and “Déjà Vu.”

Crosby admits his songwriting approach has evolved over the decades.

“The truth is it’s changed along with the years,” Crosby said. “The last few years, I’ve been writing … a lot with other people. I’ve been writing with Michael League from Snarky Puppy; he and I wrote most of this next record that’s coming out called ‘Lighthouse.’ I’ve been writing with my son James Raymond; he and I wrote most of the last record I did, ‘Croz.’ He and I have another record out called “Home Free” that we’ve just now written the final songs for. … They’re absolutely f***ing terrific.”

Working with his son, it seems Crosby has taken his own “Teach Your Children” advice, coming full circle to his youth when he would tag along to Hollywood studio sets with his filmmaker father.

“I’m doing music for films as often as I possibly can,” Crosby said. “My son James and I just did a song for a new film that’s coming out called ‘Little Pink House.’ It’s a great, great story. It’s coming out and I’ve got my Oscar acceptance speech all practiced. I’m ready. ‘I’d like to thank all the little people.'”

While his life has come full circle in many ways, his vision remains fixed on the horizon.

“I don’t look back,” Crosby said. “I think about what I gotta do today, what I want to accomplish tomorrow, what I’d like to do next week, next month, this year. My focus is almost entirely forward.”

Click here for more information. Listen to the full conversation with David Crosby below: