WASHINGTON — Magical are the moments when athletes transcend sports.

The U.S. Olympic hockey team defeating the Soviets in the 1980 “Miracle on Ice.”

Billie Jean King beating tennis star Bobby Riggs in the 1973 “Battle of the Sexes.”

And Jesse Owens delivering a symbolic blow to Nazi Germany as an African-American track-and-field star winning four gold medals to spite Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

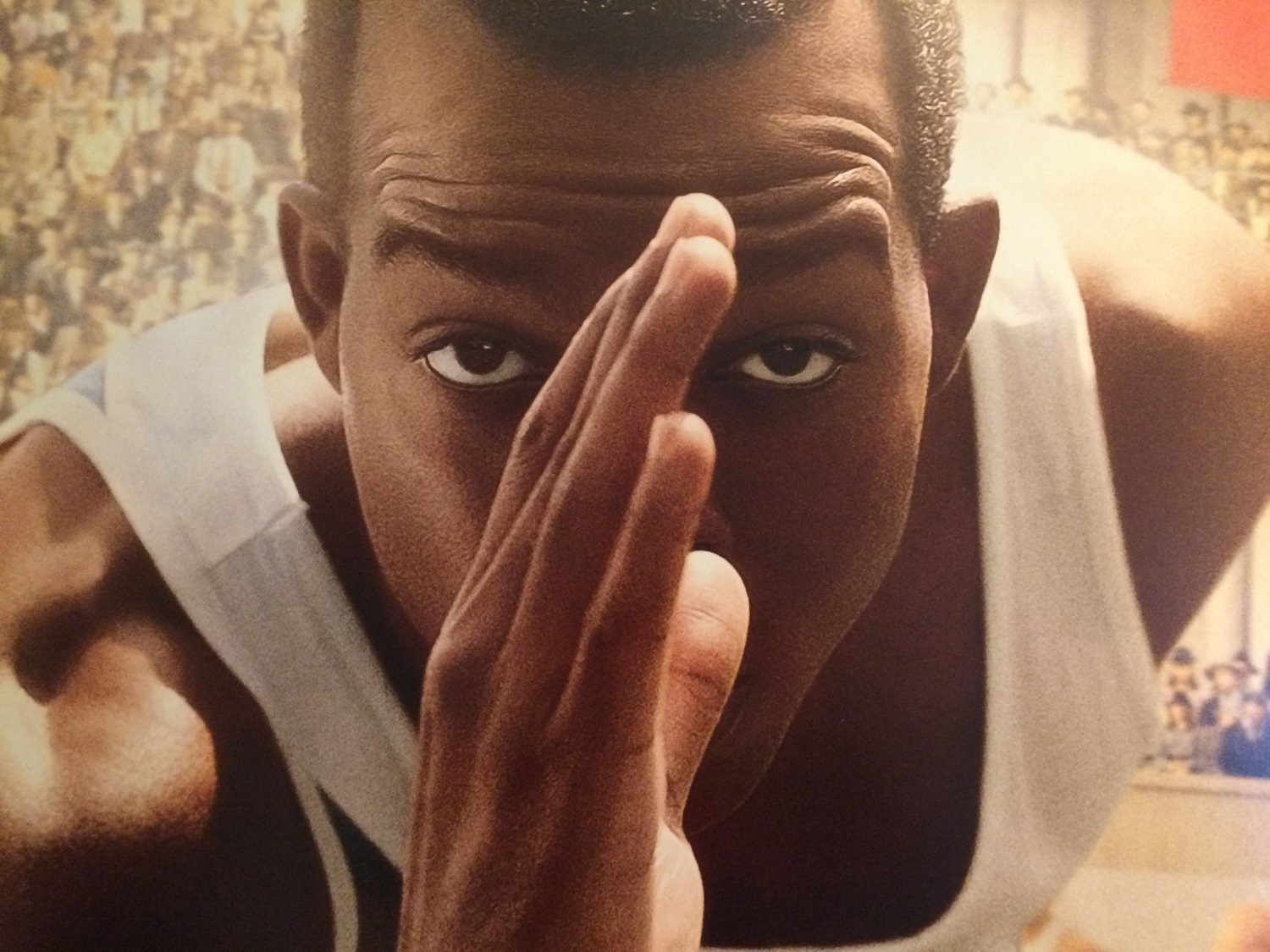

Enter the powerful new biopic “Race,” its double entendre title capturing both the sport in portrays and the social commentary it explores as the historic Owens shattered Hitler’s myth of a superior race.

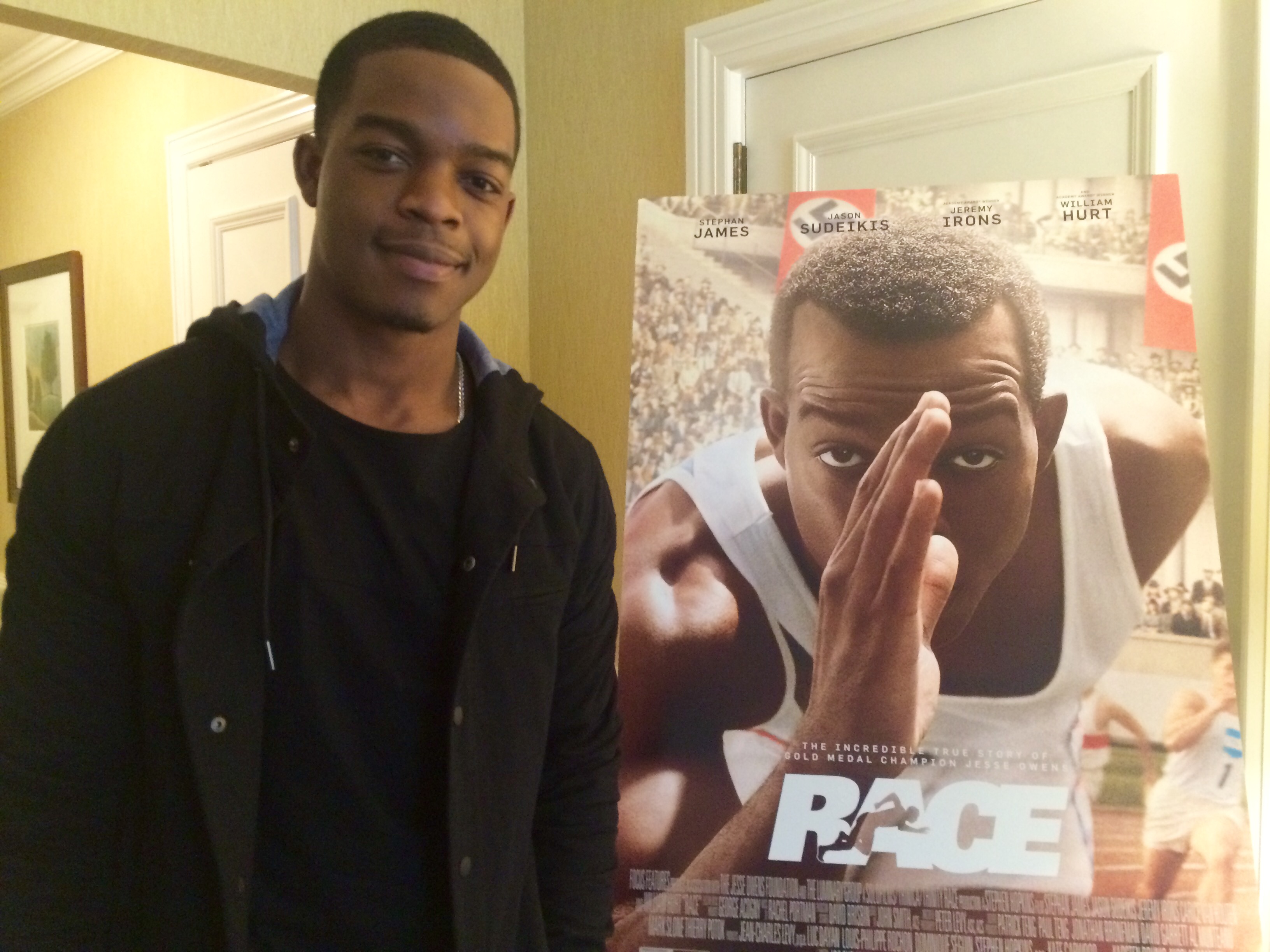

The role was originally meant for John Boyega, but when he left for “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” (2015), actor Stephan James seized the moment.

“I got a call that they’re making a Jesse Owens biopic, and the name rung a bell, but I had to scratch my head like, ‘He won those gold medals, but when did he do it?’ I didn’t really understand the story or the situation, so for me it was a whole new thing. I learned a lot about him just through playing him,” James tells WTOP.

Opening in Cleveland, Ohio, where his parents moved during the Great Migration, Jesse Owens (James) bids farewell to his family as he leaves for college at Ohio State University. It’s here that he meets track-and-field coach Larry Snyder (Jason Sudeikis), who takes Owens under his wing to set four world records in under an hour at the 1935 Big Ten Track & Field Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan, dubbed by Sports Illustrated the “Greatest 45 Minutes in Sports” — as a sophomore.

Battling college rival Dave Albritton (Eli Goree) and romancing his girlfriend Ruth Solomon (Shanice Banton), Owens earns a coveted spot on the U.S. track-and-field team for the 1936 Olympic Games. There’s one catch: the games are to be held in Berlin, the beating heart of Nazi Germany, where athletes of color — not to mention Jewish athletes — are forbidden to compete. As U.S. Olympic officials persuade the Third Reich to make exceptions, Owens weighs the morality of participating.

“Outside of him being the fastest man on the planet and being this superhuman type athlete, when I learned about the man he was, the human being he was, the father he was, the husband he was, that intrigued me so much. … It’s so important that we make films like this and never let legends die. … I really wanted to give other people the opportunity to be inspired like I was,” James tells WTOP.

The movie is itself like a track race, stumbling out of the blocks before getting its bearings, hitting its stride and kicking into a thrilling sprint for one of the most inspirational finishes in the genre.

The opening scene is a bit too obvious with on-the-nose dialogue of Jesse’s mom explaining the childhood scar on his chest and her hopes for her son’s future. This early exposition is a bit like Jesse’s untrained early sprints, charging out of the starting gate way too upright to be aerodynamic.

Fortunately, as we enter Act Two, the script is more than up to the task of building the interaction between Owens and Snyder, giving both athlete and coach a chance to be surprised at each other’s back stories. “I never knew that,” one says, as the other matter-of-factly shrugs, “You never asked.”

“(Sudeikis) grew up having a coach, being an athlete, and I grew up being an athlete and having a coach, so we knew what that dynamic was like. … As Jesse and Larry got closer in the film, Jason and I got closer in real life. … I think people will be pleasantly surprised with his performance,” James says.

Screenwriters Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse, who cowrote Halle Berry’s Golden Globe nominated performance in “Frankie & Alice” (2010), provide a fast-moving story that never once drags, painting Owens as a reluctant hero who decides he can do more good by entering the lion’s den than by boycotting the event over a lack of diversity. Cue Chris Rock at this year’s Oscars.

With such timely themes, we sympathize with Owens’ moral dilemma while focusing our anger on Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels (Barnaby Metschurat), who serves as the chief antagonist. In fact, the only time we see Hitler is at a distance as Owens enters Olympic Stadium.

This stadium entrance is the high point for Jamaican-born filmmaker Stephen Hopkins, who won an Emmy directing Geoffrey Rush in the biopic “The Life and Death of Peter Sellers” (2004). Just like Martin Scorsese used a continuous shot to show Robert DeNiro leave the dressing room and enter the ring in “Raging Bull” (1980), Hopkins constructs a masterful single-shot for Owens’ entrance.

It begins in silhouette as Owens and Snyder speak in the tunnel, then follows Owens out into the light as he shields his eyes from the sun. The camera circles our hero as he is caught up in the whirlwind of the spectacle, tilts up to see an intimidating zeppelin, pans over to the genocidal Nazi dictator, then returns to Owens. As Owens laces up his shoes, the continuous shot metaphorically places us in his shoes, the soundtrack falling silent until the sound of the starting gun triggers the rapid-cutting race.

“That was obviously a few takes. … That’s something Stephen and I talked about months before shooting. We understood the importance of that scene, how important it was to put people in his shoes and to give them a feeling of what that moment must have been like for him. … Technically, it’s a whole choreography thing. It’s really a dance between the cameraman and myself,” James says.

Throughout “Race,” there is a distinct worship of the filmmaking process, so much so that it manages to find sympathy for Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl (Carice van Houten), who follows her infamous “Triumph of the Will” (1935) by covering the games in a two-part documentary “Olympia” (1938).

The film paints Riefenstahl as less a propagandist and more as a female filmmaking pioneer, digging a pit to achieve a ground-level shot like Orson Welles in “Citizen Kane” (1941) and rebelling against Goebbels by focusing a large chunk of her documentary on the African-American stealing the show.

It begs the question: have we really come that far? It would take a full 70 years after Riefenstahl’s “Olympia” for Kathryn Bigelow to make history as the first woman to win the Best Director Oscar in “The Hurt Locker” (2008). And when Ava DuVernay was poised to become the first black woman nominated for Best Director for “Selma” (2014), she was sidelined without a nomination.

“I can’t say enough good things about (DuVernay),” says James, who starred as Congressman John Lewis in “Selma.” “With Ava, she has a way of connecting with actors that is very special, a very personable director, not that Stephen isn’t, but he has a different technique. He’s sort of a technical director and has a lot of cool shots and cool ideas … so it’s fascinating to work and pick his brain.”

Now, James will be viewed by kids as Jesse Owens the same way that Chadwick Boseman is their Jackie Robinson. It’s telling that the Robinson biopic “42” (2013) arrived before Owens got his movie, as Robinson got far more credit for breaking sports’ color barrier than Owens ever did. While Robinson’s feat occurred in 1947, Owens made history 11 years earlier in 1936, a full two years before black boxing champ Joe Louis knocked out Hitler’s hand-picked bruiser Max Schmeling.

Perhaps boxing and baseball captured the imagination of 20th-century America more than track-and-field ever could. But by the end of the film, a bittersweet gratitude hovers over Owens, who quietly marched into Berlin and punched Hitler right in his evil mustached lip, only to return home to an America where he couldn’t vote and had to enter the rear entrance of banquets held in his name.

Regardless of your present-day politics, “Race” puts a lot of things in perspective.

It also happens to be one of the most inspirational flicks in recent memory.

The above rating is based on a 4-star scale. See where it ranks in Jason’s Fraley Film Guide. Follow WTOP Film Critic Jason Fraley on Twitter @JFrayWTOP. Listen to the full interview with Stephan James below: