New research from one of the country’s leading experts in childhood development shows high-quality educational interventions in a child’s first few years of life can result in lasting economic, health and social benefits that extend beyond a single generation.

In 2010, James Heckman, a Nobel Laureate with the University of Chicago’s Center for the Economics of Human Development, analyzed the success of the Perry Preschool Project from an economic standpoint. His research found that the 1962-1967 program, which provided high-quality preschool and home visits to at-risk 3 and 4-year-olds in Ypsilanti, Michigan, had a 7% to 10% per year return on investment.

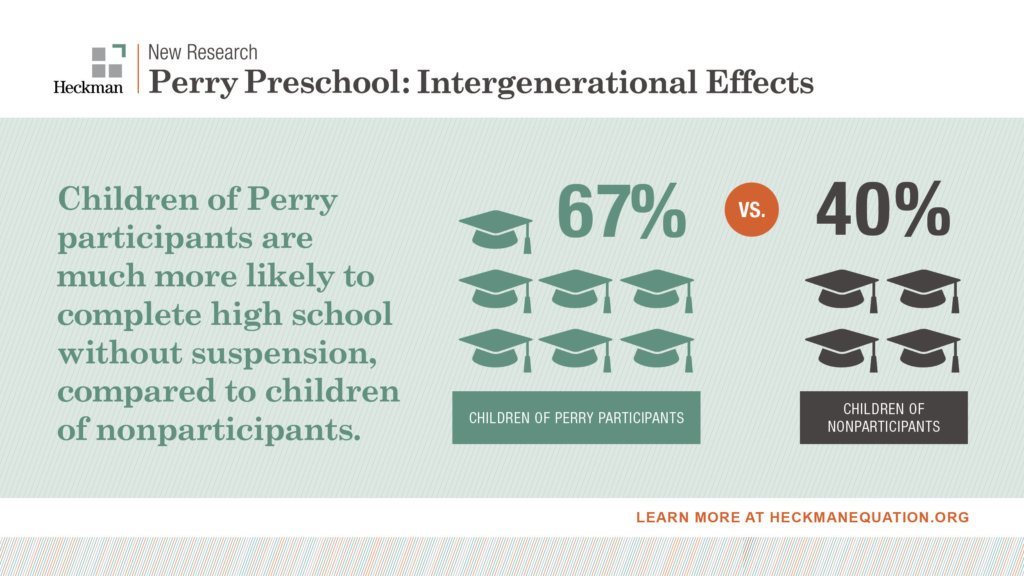

More children enrolled in the early intervention program graduated high school and had higher incomes later in life, compared to those in the control group. Plus, those exposed to the preschool curriculum and home visits had fewer arrests by age 40, compared to their peers — all of which resulted in reduced remedial education, health and criminal justice system expenditures.

Heckman’s latest research, however, extends beyond the participants of the Perry Preschool Project and looks at their children, most of whom are now in their mid- to late-20s. It finds that the children of the original Perry Preschool Program participants are “doing quite well, in many dimensions,” said Heckman, pointing to the data published May 14 in a pair of papers.

“There’s a second-generation effect,” said Heckman, who worked closely on this latest research with HighScope, the educational foundation behind the original 1960s program.

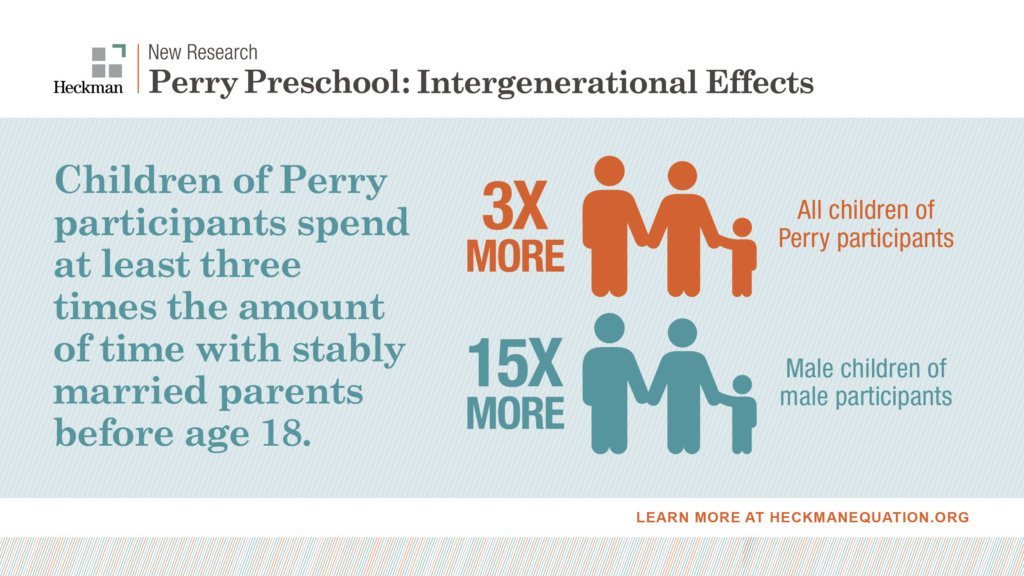

Similar to their parents, second generation Perry participants were more likely to advance their education and stay out of trouble, both at school and with the law — and a lot of it has to do with an improved home life. Heckman said because individuals in the original treatment group, most of whom are now in their mid-50s, were less likely to go to prison and were more likely to maintain stable marriages, they created healthier home environments for their children.

“For the first time, and I stress this is the first time, we have experimental evidence about how the case for early childhood [education] propagates across generations,” Heckman said.

The study debunks the idea that the outcomes measured in the second generation are tied to changes in geographic location (moving to more affluent neighborhoods and better school systems.) In fact, many children of Perry participants live in neighborhoods that are “similar or slightly worse off” than the ones their parents lived in.

“So this is not a consequence of people changing ZIP code. These results are literally a consequence of improving, bolstering families,” Heckman said.

The researchers also make a point to emphasize that the success of the program shouldn’t be attributed to curricula, alone. In addition to analyzing the children of the original participants, Heckman surveyed the siblings of participants who were not in the preschool classroom, but were in the home at the time. He found measurable social and educational benefits in their lives as well.

“Why? Because the home visiting and the activity around the home that the first group of individuals received carried over to the whole home environment,” Heckman said.

“It seems like the universal ingredient is enhanced parent-child interactions — stimulation that stays on at the home and continues throughout the child’s life.”

Science shows the first few years of life are some of the most important when it comes to brain building and establishing social and emotional connections. And as for a more broad application of early childhood education — an issue that remains at the top of the list for many political hopefuls — Heckman said, “The evidence from this study and from other studies like it show targeting children from disadvantaged families is a very effective strategy.”