It was a scene straight out of a disaster movie. At the height of morning rush hour, Canal Road — a busy commuter route — looked more like the C&O Canal. And the transformation from road to river happened in seconds.

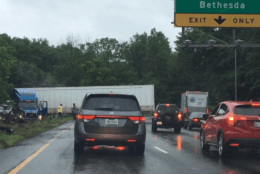

During the heart of the Monday morning commute, the District and nearby suburbs experienced a true flash flood emergency. Drivers were stranded. Roads were washed out.

The sudden onslaught of water felt eerily similar to a flash flood that I covered last July along Broad Branch Road in Rock Creek Park. I had been in flood-ravaged Ellicott City two months earlier. Having witnessed flash flooding on numerous occasions, it was clear to me that a dangerous situation was about to unfold along the steep slopes of the Potomac bottoms.

I pulled onto MacArthur Boulevard in Palisades around 8:30 a.m. It was pouring. Each puddle I passed seemed to be deeper than the last, with whirlpools swirling around overwhelmed storm drains and manholes that looked more like geysers. Knowing the worst was yet to come, I parked on higher ground as runoff rushed between my tires and downhill toward Fletcher’s Cove.

Down below, a perilous combination of heavy rush hour traffic and heavy, flooding rains was brewing.

I ran down Reservoir Road. The steeply sloped road resembled a river as water cascaded off the nearby bluffs. Through the din of the downpour, I heard shouting and leaned over a ledge. Below, I didn’t see Canal Road; instead I saw a “road canal” and dozens of vehicles idling in high water. Some people were yelling at the drivers behind them, pleading for those upstream to reverse course. They were trapped between rising floodwaters and bumper-to-bumper traffic.

I ran down to Canal Road near Fletcher’s Boathouse, and looked toward Georgetown. From slightly higher ground, the potentially lethal threat became apparent. Canal Road is a reversible, two-lane road. During morning rush hour, both lanes are only open to inbound traffic between Arizona Avenue and Georgetown. The drivers who were stuck were on a one-way road with no way out. And the water was rising rapidly.

I ran between vehicles, starting at the back of the queue, knocking on doors and telling each driver to turn around as quickly as possible. With exceedingly poor visibility and stuck in traffic, many of them didn’t realize what was happening just out of view and had settled on waiting the traffic out, unaware that they were physically blocking the only escape route.

As I ran farther down Canal Road, the water kept getting deeper but I was determined to reach the front of the line. About 500 feet from Fletcher’s Boathouse, in chest-high water, I climbed onto the rock wall. From there, I could see several vehicles submerged. A Mini Cooper was bobbing up and down in the middle of the road. Its driver, Greg, was standing on the wall some distance away.

“It just stalled out in the high water and the water started coming up to where the doors are. My head was always going to be above the water line but I jumped out anyway,” Greg told me. His business attire was drenched. He said he side-stroked away from his vehicle when it became clear he had no better options.

In the distance, I could make out a Mercedes and yet another vehicle through the curtains of rain. I tried to make my way toward them but it was simply too unsafe to proceed. Whereas the floodwater near the main cluster of submerged vehicles was relatively still, a torrent of white-water was bursting down a run, charging across the carriageway and spilling over the rock wall into the C&O Canal not too far away. The rapids looked like a miniature Niagara Falls as they were thrust upward above the wall.

D.C. Fire and EMS units were on their way, from stations on both ends of Canal Road. But they hadn’t arrived yet. I turned to another man standing on the roof of his Audi sedan. William Digges was on his way to work at the Tax Foundation near Metro Center when he suddenly found himself besieged by rising water and wall-to-wall traffic.

“I noticed the water levels going up. I look over at the car tire next to me, and it’s up a quarter of the way. I look over a minute later, and it’s up half the way. Three minutes later, their whole tire is covered,” Digges said.

Monday morning’s rainfall was exceptional for any place on Earth, especially for the D.C. area. Born from anomalous moist, tropical air, more than three inches of rain was unleashed in just one hour at Reagan National Airport a couple of miles downriver. The flash flooding and runoff that resulted was equally fierce.

“People always say ‘don’t drive through water you can’t see to the bottom of.’ Me and the people I was stuck with, we didn’t even try to drive through it — the water came to us, and there was no way to get away from it because all the other cars were blocked in behind us,” Digges said.

He managed to crawl through the sunroof of his waterlogged A4 and emerged into the blinding downpour dressed in a brand-new Blue Windowpane suit. A father and his young son were following Digges’ lead nearby. They crawled onto the roof of their Honda, the dad consoling the distraught child.

With a sullen look on his face, Digges was clutching a soaked, inoperable iPhone. Standing alone on the roof of his car, he asked me to call his father in Virginia to let him know that he would be okay. I obliged. It was the least I could do.

Digges gashed his arm. The boy and several others were shaken. But no one was killed and there were no serious injuries during the Monday commute from hell on Canal Road. Rescue services arrived on scene as the water began to recede. Soaked from head to toe, some of the woebegone commuters were escorted to higher ground by D.C. firefighters through the water on foot. Others were brought to safety by inflatable boats. They were taken to a nearby fire station.

I reconvened with Digges at his office downtown a few hours after the ordeal.

“I don’t know where my car is,” he told me.

He may have lost his car, but Digges gained a newfound respect for the power of water: “You don’t know when it can strike. And with flash floods, people always say ‘it comes out of nowhere’ and ‘before you know it you’ll be underwater’ … it really can happen.”

The slogan “turn around, don’t drown” is ignored by many. But having seen the dangerous combination of heavy traffic and heavy weather before, I can tell you that keeping yourself safe during flash flooding is not always cut and dry, especially on limited-access highways and confined parkways. As a driver, the issuance of a flash flood warning is your cue to reroute to higher ground. That means avoiding roads with low water crossings and those that run through stream valleys and along rivers.

Flash floods are the number one weather-related killer in the United States and the frequency of these events appears to be increasing locally. With Monday’s rainfall in the books, four of the D.C. area’s Top 10 rainiest July days ever occurred in the last three years.