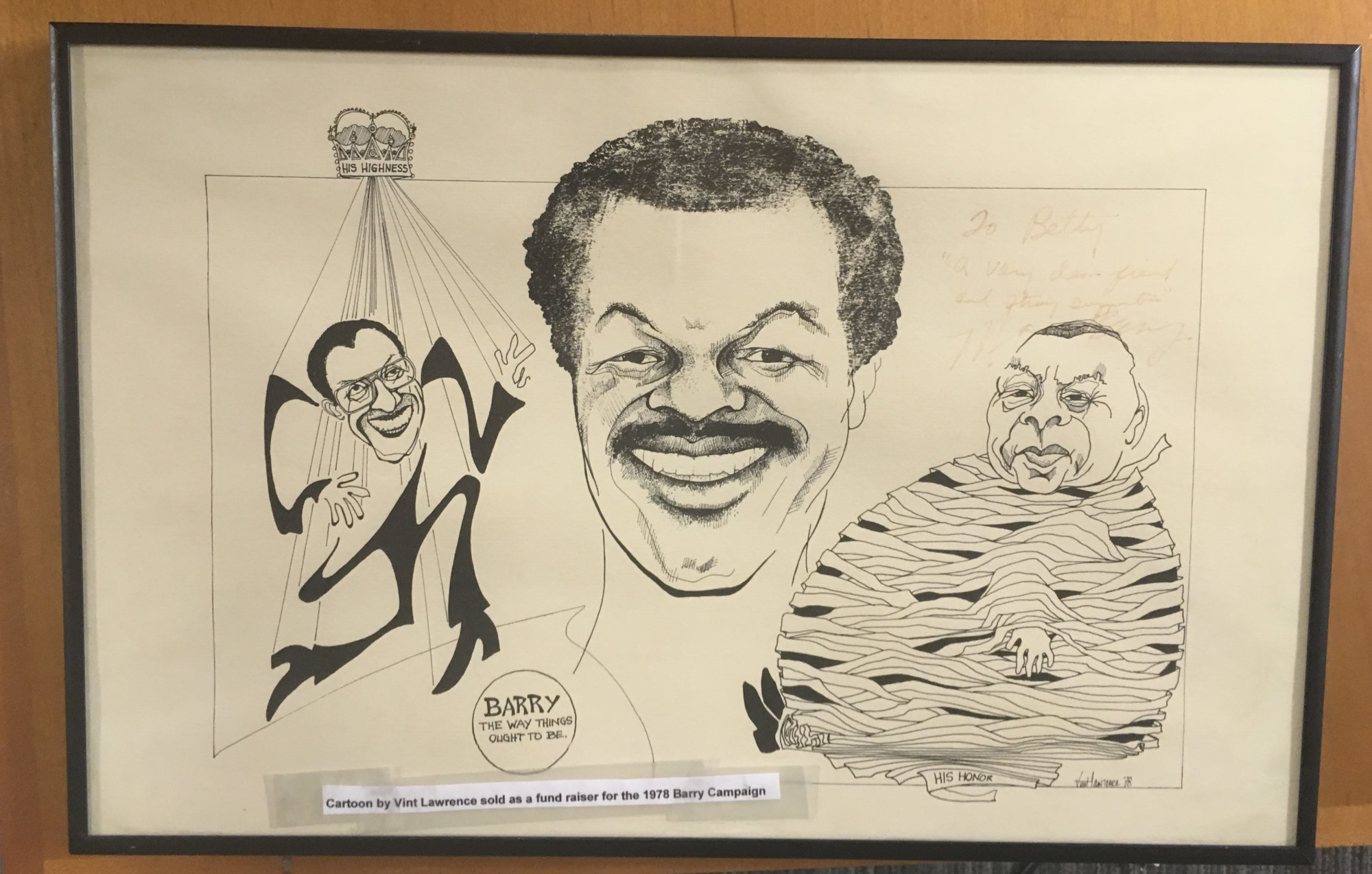

This is the final part of WTOP’s three-part series “The making of Marion Barry,” marking the 40th anniversary of the first election of the man referred to as D.C.’s “Mayor for Life.”

WASHINGTON — When Marion Barry began to run for mayor of D.C. in 1978, he could point to his record on the D.C. Board of Education and the D.C. Council, where he had been chairman of the Finance and Revenue Committee and had proposed more than a few innovative ideas for bringing more money into the District while holding the line on taxes.

Still, in the September Democratic primary, he’d be up against the incumbent mayor, Walter Washington, and council Chairman Sterling Tucker.

Vincent Gray, a member of the D.C. Council and a former mayor, told WTOP that as the executive director of the nonprofit now known as The Arc in 1978, he wasn’t directly involved with politics, but the bruising race was impossible to ignore.

“How could you not pay close attention to such a competitive race?” Gray said.

Barry spent the primary campaign talking about the “bumbling and stumbling” of the Washington administration, and promising a dynamic, forthright leadership for the District.

I think Marion believed that, as black folks, we can do better.

— Former Washington Post writer Milton Coleman

“I’m pretty certain that Marion and Ivanhoe [Donaldson, Barry’s campaign manager] had respect for the Walter Washington generation, for what they had done,” former Washington Post writer Milton Coleman told the Marion Barry 1978 Mayoral Campaign Oral History Project at the George Washington University’s Gelman Library.

“It was no easy task for Walter Washington to do what he did. But, to steal a phrase from Barack Obama, I think Marion believed that, as black folks, we can do better. … And that was, I think, the tenor of the time,” Coleman said.

Veteran journalist Tom Sherwood, who has covered D.C. politics for years and co-authored with Harry Jaffe the essential history “Dream City,” told WTOP, “The ’60s were an amazing time of discomfort and demands that things had to be better. And that moved on into the ‘70s. … There was less tolerance about getting along and going along. Power doesn’t give up easily — you have to confront power. That’s what Barry was able to do.”

Read Part 1: “A DC mayor’s activist beginnings in the South.”

Read Part 2: “Street activist to power player.”

A pocket full of change

Barry wouldn’t have won a battle of resumes, observers remembered, and his opponents each had some well-established voting blocs. He had to do something different, and he did: He built a coalition that reflected the city D.C. was coming to be.

Operating out of an old fur store on G Street downtown, the Barry campaign ran with the passion and energy of people who didn’t know they were underdogs, led by a candidate who campaigned for mayor the same way he worked in the civil rights movement: Being among people and talking face-to-face.

Barry’s widow, Cora Masters Barry, told the GW project, “Marion would go and do a lot of meet-and-greets. It would be 10, maybe 15 people at the most in a place. He’d go in people’s basements and their backyard. …”

“That was the kind of campaigner he was. I mean, I would just pick people off the street — ‘What’s your number? Would you like to speak to Marion Barry?’ And I’d say, ‘I just met this person at the bus stop. I want you to call them.’ Some people don’t understand. That’s worth 10, 15, 20 votes.”

It’s been said that Barry kept a pocket full of change and couldn’t pass a pay phone without reaching out with a few phone calls, from the endless list of numbers he kept in his head. LaToya Foster, who worked for Barry and is now the spokeswoman for Mayor Muriel Bowser, knew Barry in the cellphone era, but could vouch for his memory — “Even days before his death, the number of anyone he wanted to reach, he could give you off the top of his head.”

The coalition

“There was no passion anywhere but in our campaign,” Loraine Bennett, Barry’s Ward 1 coordinator in 1978, told the GW project.

Lucille Knowles, a volunteer on the 1978 campaign, said it wasn’t an “it’s not my job” kind of campaign. King agreed, telling WTOP, “Everybody did everything. If something needed to be done, somebody did it.”

By the end of Barry’s life, in 2014, it might have been hard to believe that the decisive factors in the race would be white voters, gay voters and the backing of The Washington Post, but those who saw the campaign unfold remember that that’s exactly how it shook out.

And, though Barry had long moved from street-level activism to working within the system, the grassroots campaigning skills he’d developed in his civil rights days helped him develop the coalition that put him over the top.

“Our mantra was that we were running to help the least, the lost and the left out,” King said. “And all of that was what he talked about wherever he went.”

That message resonated with people all over D.C., even with voters who might not be expected to back Barry — and who didn’t in later years.

The Washington Post

On Aug. 30, 1978, The Washington Post — the voice of establishment, white D.C. — shockingly endorsed Barry, the former street activist, for mayor of D.C.

While praising Tucker’s qualifications, the paper placed more weight on Barry’s “energy, nerve, initiative, toughness of mind, an active concern for people in distress.” They said he would bring to the mayor’s office a “genuinely bold, alive commitment to actually making things happen, and a critically important belief that things can be done.”

… there was really something special about him, about the times, generally, and about that moment for this city.

— Kwame Holman

The paper foreshadowed some of the problems in Barry’s mayoralty by conceding, “True, he would bring a certain sense of adventure to City Hall — which means that there is a certain risk involved.”

Still, the endorsement was a galvanizing moment. Speaking to the GW project, Knowles called it “a real point where it looked kind of possible that he could actually win.”

Sherwood called the Post endorsement “crucial … particularly [for] the white communities.” And, it wasn’t the only editorial the Post ran supporting Barry in the last weeks of the campaign.

“He was definitely the candidate of the white precincts in that first election,” King recalled to WTOP.

“The ‘78 campaign, and the terrific support we got from the white community, was based on [the belief that], ‘It’s time for us to take control of our fate, and this is the guy who’s going to make a significant difference.’ And, he did.”

Kwame Holman, Barry’s driver during the campaign and, later, the political and congressional correspondent for “The PBS NewsHour,” told the GW project: “Marion would walk into a fundraiser in Ward 3 and light up in the room in the same way he would in any other ward. And again, this was what made you feel and understand that there was really something special about him, about the times, generally, and about that moment for this city.”

Sherwood explained that white voters backed the most activist black candidate in the campaign because some of the issues he brought up transcended race.

“The white vote in the District of Columbia is a liberal white vote,” Sherwood told WTOP. “ … And the white people are politically attuned, both to national and local issues. The civil rights movement was a moral imperative; Barry represented that — the chance to have black people run the city government like never before.”

The gay vote

Near the end of Barry’s life, he came out against a marriage-equality bill in the D.C. Council, citing opposition from the African-American religious community. But, he had been a supporter of gay rights throughout his career, and in 1978, he used the instincts he’d developed in the civil rights movement to court D.C.’s gay community for the first time.

“The civil rights movement … is a matter of coalition-building — getting people who have common interests to overcome their common disagreements,” Sherwood said. “And, that’s what Barry would do. He was looking for every vote he could get.”

Activist Richard Maulsby, the founder of the Gertrude Stein Democratic Club, D.C.’s gay Democratic organization, told the Barry oral history project that not only Barry but allies Ivanhoe Donaldson and Courtland Cox “all [came] out of SNCC, of course. I mean, they all got it. They saw the parallel between what we were trying to do and what they had done with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and so there was a real simpatico there. …”

“He supported gay pride resolutions on the [D.C.] Council,” Maulsby added. “I mean, he was just far and away the leader. And, others came after him. Because of what he did, it was easier for other people to do that.”

They held fundraisers for Barry, as well as staffing the phone banks and stuffing envelopes, Maulsby said. “During those hot summer months leading to the September primary … most of the people who worked the phone bank at night were people from the gay community.”

King recalled that people respected Barry’s sincerity because he made his support for civil rights clear wherever he went.

“My women friends were very impressed that when they went to see Marion talk [at a general-audience event], he was talking about gay rights and women’s rights, just as he did at a women’s luncheon,” King said. “His agenda was his agenda.”

In the three-way race, each candidate was accused of being a spoiler who would split this or that segment of the vote and throw the election. In Barry’s case, he was charged with splitting black people’s support with Tucker, thus ensuring a Washington win.

Just weeks before the Sept. 12 primary, Barry was asked to meet with Tucker and other D.C. political figures late on a Saturday night. He feared that the real intent of the meeting was to pressure him to drop out. The newspapers picked up the story, and it redounded badly for Tucker.

In the end, the gap between first and third was less than 3,000 votes. There was a recount. But, Barry emerged as the Democratic nominee and would later cruise to victory in the general election on Nov. 7, 1978.

“There was no way we could win,” Betty King said — “except we did.”

Epilogue

King gave credit to campaign manager Ivanhoe Donaldson, calling him “a remarkable strategist.” She recalled Donaldson coming to her house about a month before the election and saying, “What we are going to do is, we’re going to win Wards 1, 2, 3 and 6. We’re not going to disgrace ourselves in 4 and 5, and we’ll do what we can in 7 and 8.’ And, that’s exactly what happened.”

“I had learned something, which to this day affects my view of politics on every level,” Coleman told the GW project. “The way you win an election is, you don’t declare yourself a candidate and go out and make your pitch and get people to come over to your side. … You declare yourself a candidate, you identify your people, and you get them to the polls. And, you don’t worry about the other people.”

King told the GW project that the day after the primary, the pollster from The Washington Post came to see Barry to ask how he’d pulled it off, and how the Post’s polling had gotten the race wrong.

“Marion said, ‘You were polling habitual voters, and we got the nonhabitual voters to vote and we got new people to register,’ and that was what made the difference,” King said.

In the general election, Barry beat Republican Arthur Fletcher with about 70 percent of the vote. On Jan. 2, 1979, he was sworn in by Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice.

Barry, of course, made national news in 1990 when he was arrested after being caught on video smoking crack and fondling a woman who was not his wife in a D.C. hotel room. There had been rumors for years about drug use and adultery. Several members of his administrations, including Donaldson, were convicted of corruption charges. When Barry returned to the mayor’s office, Congress stripped the office of much of its financial powers.

But, observers told WTOP that while those factors complicated Barry’s legacy, the District has been changed for the better for Barry’s having been mayor, especially in his first term.

[He] recognized that in order to make real change, he had to become a part of the system he’d been fighting against. … And, he made a lot of change.

— Former D.C. Mayor Vincent Gray

For one thing, he made the government of the city look like the city.

Before home rule, many of the bureaucrats in the D.C. government didn’t even live in the District — the city was run by federal officials like a program of the federal government, and Sherwood recalled the suburbs being referred to as “the 10th Ward.”

Gerald Bruce Lee, the Pride Inc. kid from Anacostia High who became a federal judge, said, “Young people use the word ‘woke’ – he was woke in the ‘60s. … He made businesses in the city recognize that there was economic power in the people who lived in the city … and that people who were spending money at Hechinger’s deserved a store at Benning Road and H Street. … That people who were buying their groceries at Giant deserved a chance to work at Giant.”

Barry also created a government version of Pride Inc. — a summer-jobs program that sought to provide a job for any young person who wanted one. It continues to this day, and current D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser recently renamed it the Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program.

“It’s amazing, the number of people in this city who say, ‘I got my first job from Marion Barry,’” Gray said. “And, it’s amazing and it’s well deserved that he was remembered that way.”

It also created a durable political base for Barry — one that stuck with him through his personal and political troubles.

“He said things that people were afraid to discuss, in a real-person manner,” Foster said. “People felt he was there for them.”

Barry died in 2014, but his work continued to bear fruit, including most recently the D.C. Fatherhood Initiative, Foster said. And, a statue of Barry stands outside the Wilson Building, formerly the District Building.

“It’s important to remember Marion for who he really was,” Gray said. “So many people want to define him [by] the foibles he had as a human being. That’s not really Marion. That wasn’t him. What he did was to try to uplift people — to get them to a different place. And, there are so many people today who are in a better and different place because he was a leader and he lived.”