This is the first part of WTOP’s three-part series “The making of Marion Barry,” marking the 40th anniversary of the first election of the man referred to as D.C.’s “Mayor for Life.”

WASHINGTON — Seemingly every successful political campaign says it ran a different kind of campaign. But Marion Barry’s first campaign for mayor of D.C., which reached its ultimate goal 40 years ago this week, reflected a change in how the District governed itself and saw itself.

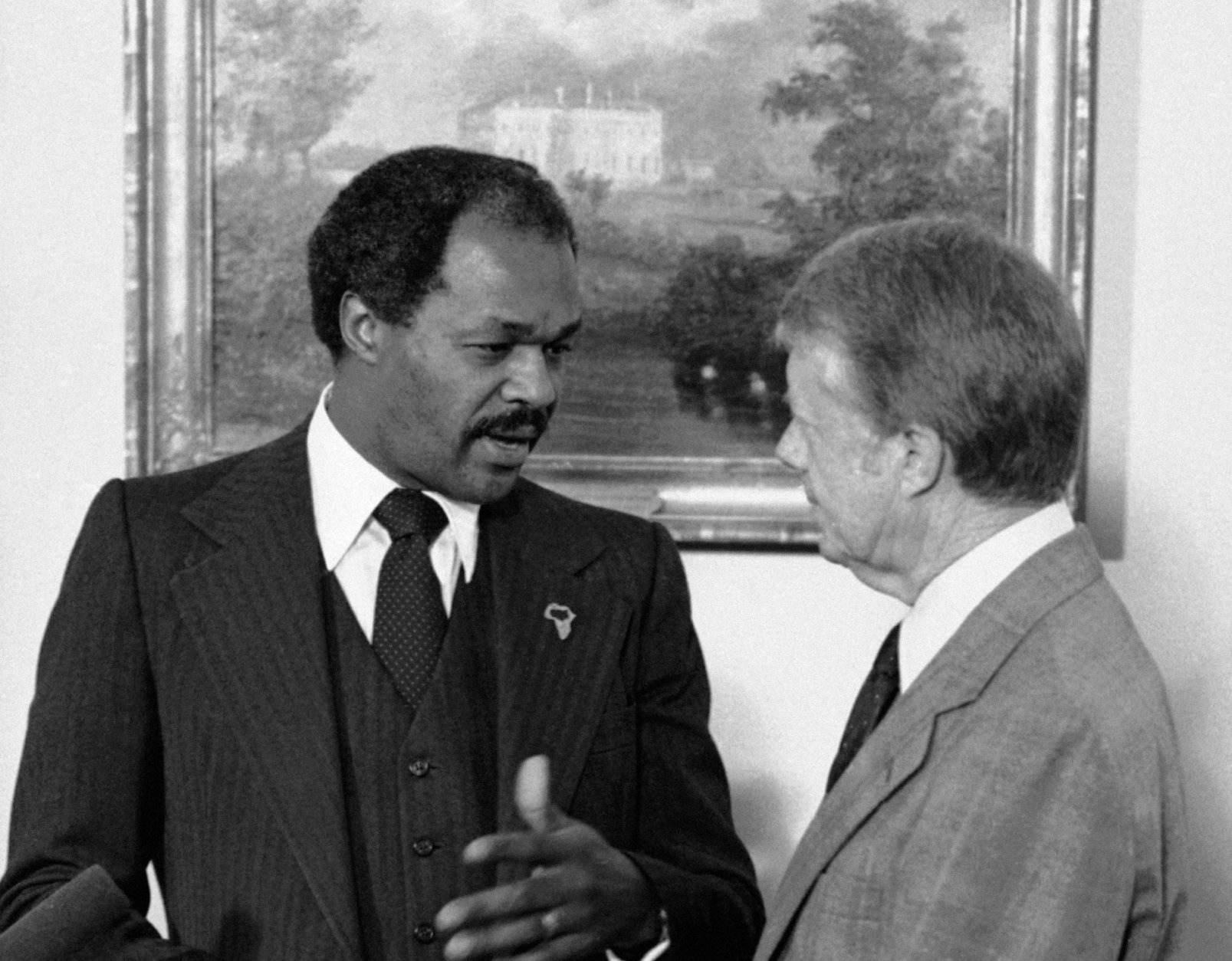

Barry wasn’t D.C.’s first black mayor, nor was he the first mayor the District’s voters picked for themselves under home rule. His predecessor, Walter Washington, held both of those distinctions. But Barry’s election, made virtually certain when he unseated Washington and vaulted over Council Chairman Sterling Tucker in the September Democratic primary, was both a cause and a result of the District coming into full flower as an independent and black-run city.

Vincent Gray, a member of the D.C. Council and a former mayor himself, told WTOP that he remembered Barry as “a phenomenal force.”

“Marion Barry really is known, not as the first mayor, but [as] the one who stepped out,” Gray added.

“Marion’s election was a breath of fresh air,” said Absalom Jordan, a member of the Advisory Neighborhood Commission for Ward 8, who knew Barry for decades.

It came “as D.C. was transitioning and getting a footing of what it meant to be a predominantly African-American-controlled city,” Denise Rolark Barnes, publisher of the Washington Informer, told WTOP. “A person who was very clear about who he was and his blackness, so to say, was what folks in the District were looking for.”

Not by much: In the three-way primary race, Barry won by only 1,356 votes over Tucker and 2,979 over Washington. But he was on the way; he won the general election with 70 percent of the vote over black Republican Arthur Fletcher. He would win the next two mayoral elections, in 1982 and 1986, as well.

Barry had only lived in the District 13 years when he was elected, and he didn’t seem like the mayoral type when he arrived: “The champion of the street dudes” is how fellow activist Courtland Cox remembered him — a dashiki-wearing orator who spoke casually of the possibility of getting “beat to death” by the police and who was arrested multiple times in D.C.

But Barry could move between “the suites and the streets,” as veteran reporter Tom Sherwood described it, to create the signature jobs program Pride Inc., which created jobs for at-risk youth and ex-offenders. He eventually put on a suit, ran for the School Board and the D.C. Council and in both places talked about holding the line on taxes.

In the process, he demonstrated an acuity for the budget process that might have surprised those who didn’t know he was a dissertation short of a Ph.D. Observers say he demonstrated what the activism of the 1960s could move into as the decade changed.

“He was one of those civil rights leaders who recognized that in order to make real change he had to become a part of the system he’d been fighting against,” Gray said. “And he converted himself from being outside, working to effectuate change, to being somebody who was inside having the authority and the opportunity to make change. And he made a lot of change.”

Barry’s method of campaigning was heavily influenced by his work in the civil rights movement, and it was likely the only way to get past two heavily favored candidates. In the process, he built a very different coalition than had come before: heavy support from white voters in Wards 2 and 3, and from a gay and lesbian community that he energized politically for the first time in city history.

That was a voter base very different from the one he relied on later in his career, in the process laying the groundwork for the personal affection people had for him that carried through the difficulties he got himself into.

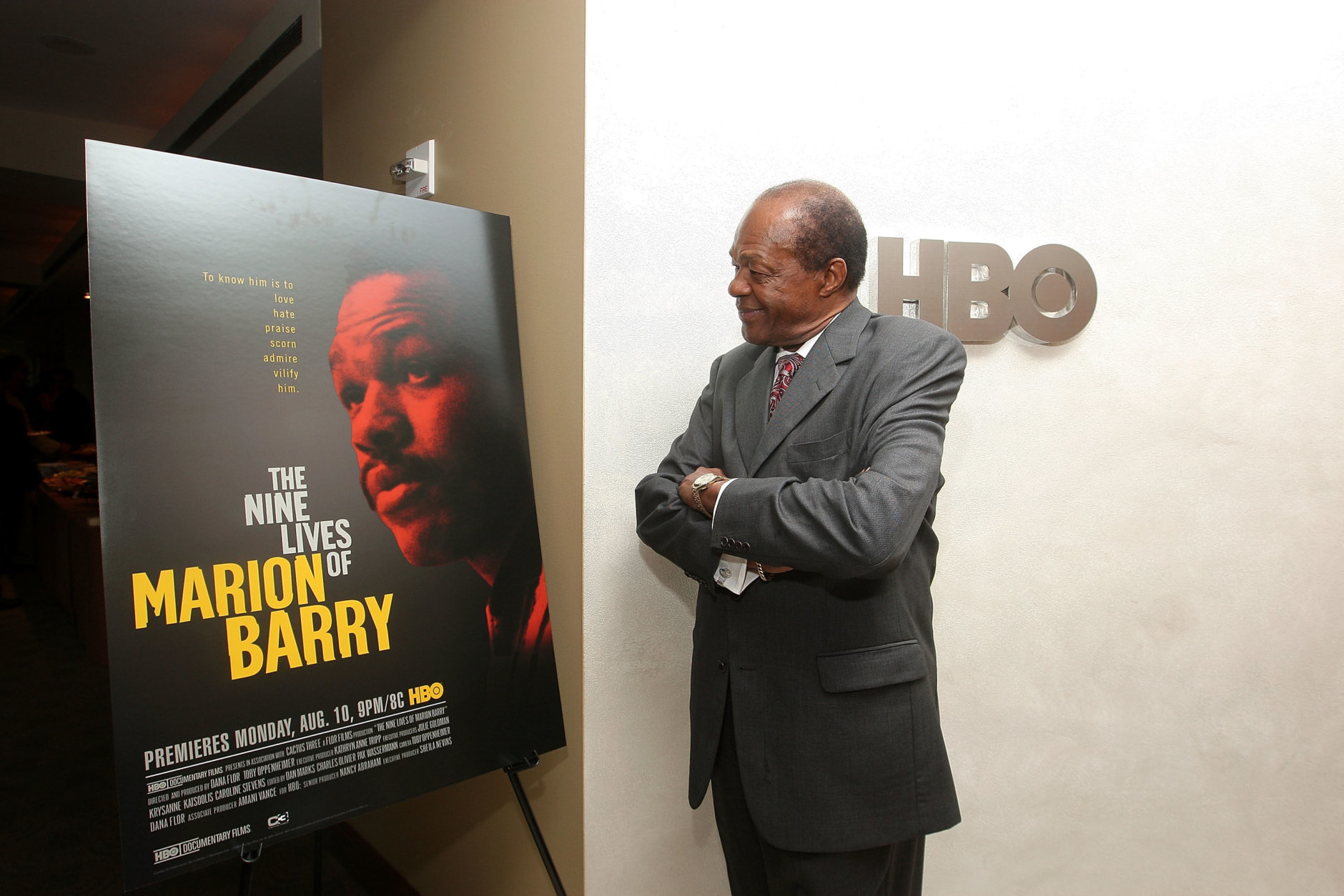

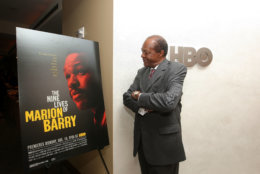

The popular image of Barry is dominated by his legal troubles, and not without reason. He was convicted of drug possession in 1990, assault in 2000 and tax avoidance in 2005, and crack was discovered in his car in 2002. But he remained politically viable through it all, returning to the mayor’s office after his drug conviction in 1994, and to the D.C. Council in 1992 and 2004.

In 1998, after Barry announced he wouldn’t run for a fifth term as mayor, Sam Smith, editor of the Progressive Review, who had been covering him for more than 20 years, wrote, “The best way I can describe it is, it’s like going out into a field and seeing an old rusting-out hulk of a car and trying to imagine what it was like when it was brand-new. What people are seeing now is that corroded shell of what Barry was, and if you don’t remember that [brand-new car], it’s very hard to see.”

To understand the District of Columbia, one must understand Marion Barry.

— The Washington Post

Barry had at least two political rebirths in his career, depending on how you’re counting, and a lot of people outside the District — and inside — saw them as cult-of-personality triumphs by a hopelessly corrupt leader with the help of the followers he’d bought off or mystified.

But “To understand the District of Columbia,” The Washington Post once wrote, “one must understand Marion Barry.” And a look at the election of 1978 goes a long way to explaining the bond the mayor had with the city, which lasted until his death in 2014.

‘Larger than life’

Albert Beveridge, who helped him with a legal challenge that cleared the way for his first election, told the Marion Barry 1978 Campaign Oral History Project at the George Washington University’s Gelman Library that “Marion Barry was larger than life, even before he became mayor.” Ivanhoe Donaldson, his 1978 campaign manager, told the GW project Barry began to run for mayor of D.C. “the day he was born.”

Marion Barry was born in Itta Bena, Mississippi, about 15 miles from Greenwood, in 1936. He told the Oral History Project of McComb (Mississippi) High School in 2011 that his parents were sharecroppers and they lived in a shotgun house with no electricity or indoor plumbing. Before he was old enough to go to school, his mother would take him into the fields while she worked.

Then, Barry went to a one-room schoolhouse with one teacher for 40 kids. “I don’t remember learning very much,” he said.

Mainly, he would watch the Greyhound bus go by on the way to Chicago, and wish “we were on that bus, getting the hell out of there.” He noticed early on that white students got to ride a school bus, but he had to walk.

When he was 8 years old, his mother moved the family to Memphis, Tennessee, later remarrying. The story is that Barry’s father died when he was 4, but in his autobiography he said his mother took the family away from a father who was not quite abusive but overly controlling. “I only told people [my father had died] later on in high school to avoid the shame of not having my father in my life anymore.”

He wrote that his mother worked as a domestic for white women in Arkansas, “but she had a rule where she always insisted that she go in through the front door and not through the back. She told them to call her by her last name, Ms. Barry. … My mother earned her respect and showed me how to earn it.”

Barry faced discrimination early: In his memoir, he said, he and several other black Memphis paperboys hit the sales quota that would earn them a trip to New Orleans. The paper wouldn’t let them go, citing the extra expense of a separate bus for the black paperboys, which the segregated city of New Orleans would require. Barry boycotted his route; he and the others were eventually rewarded with a trip to St. Louis instead. He’d also drink from whites-only fountains and go to the Memphis Zoo on whites-only days, and in college walked out of a Draft Board hearing when a white chairman called him “boy.”

‘Nobody was protesting’

In 1958, as a senior at LeMoyne-Owen College, the NAACP (of which Barry was LeMoyne chapter president) sued Memphis over segregated seating on the city buses. A white man on the LeMoyne board “said some negative things about black folks in his argument to the court,” remarks Barry found “condescending,” he told the McComb students. He wrote to the president of the college asking for the board member to resign or apologize. Eventually, the letter was published on the front page of the Memphis Commercial Appeal.

“Nobody was protesting,” Barry told the students; “nobody was raising hell. People were accepting that segregated situation because white people had conditioned us to accept that.”

The next day, the LeMoyne president — a black man — called Barry “an embarrassment to the college” and said he had to dismiss him. It was three weeks before graduation. “I said no, you’re not going to dismiss me,” Barry remembered. “We’ll close this college down.”

He wasn’t dismissed — the president “thought it was better to get rid of me,” Barry wrote later. He graduated, and in 1960, he was working on a master’s in chemistry at Fisk University when he helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and, as its first chairman, began spending more and more time at sit-ins, marches and demonstrations, including some of the first sit-ins at lunch counters in Memphis. He continued his activism when he began working on a Ph.D. in chemistry, first from Kansas University and then from the University of Tennessee.

What use was getting an education if you couldn’t get a job, or vote, teach where you wanted to teach, or live where you wanted to live?

— Marion Barry

Students, he explained in his book, had the most to gain from civil rights: “What use was getting an education if you couldn’t get a job, or vote, teach where you wanted to teach, or live where you wanted to live?” Eventually, his civil rights work took over from his academics, and Barry devoted himself to the movement full-time. He completed all his doctorate course work but never wrote his dissertation.

Soon he was sent back to Mississippi — to McComb, city in the south of the state of about 12,000 located 30 miles south of Jackson and 180 miles south of Itta Bena, to organize.

One of the organization’s trademark methods, Barry remembered, was for members to stay in the houses of local families. That gave them the kind of connection that could come in handy in the face of a backlash from white local police, and also formed a bond of understanding.

“You don’t understand the conditions until you really are in the conditions, and seeing people live the way they do,” Barry told the McComb High School students nearly 50 years later. “You never get it until you get it right up here — right in your front door. When you’ve got to live it, and you see the hurt, see the pain, see the tiredness.”

That way of creating a bond would come in handy when his political career began.

Barry worked with SNCC in New York for a few months before being sent to D.C. in 1965. He was dispatched “to raise funds, not hell,” Milton Coleman wrote in The Washington Post decades later. But, that didn’t last long.

Read Part 2: Street activist to power player

Read Part 3: ‘There was no way we could win‘