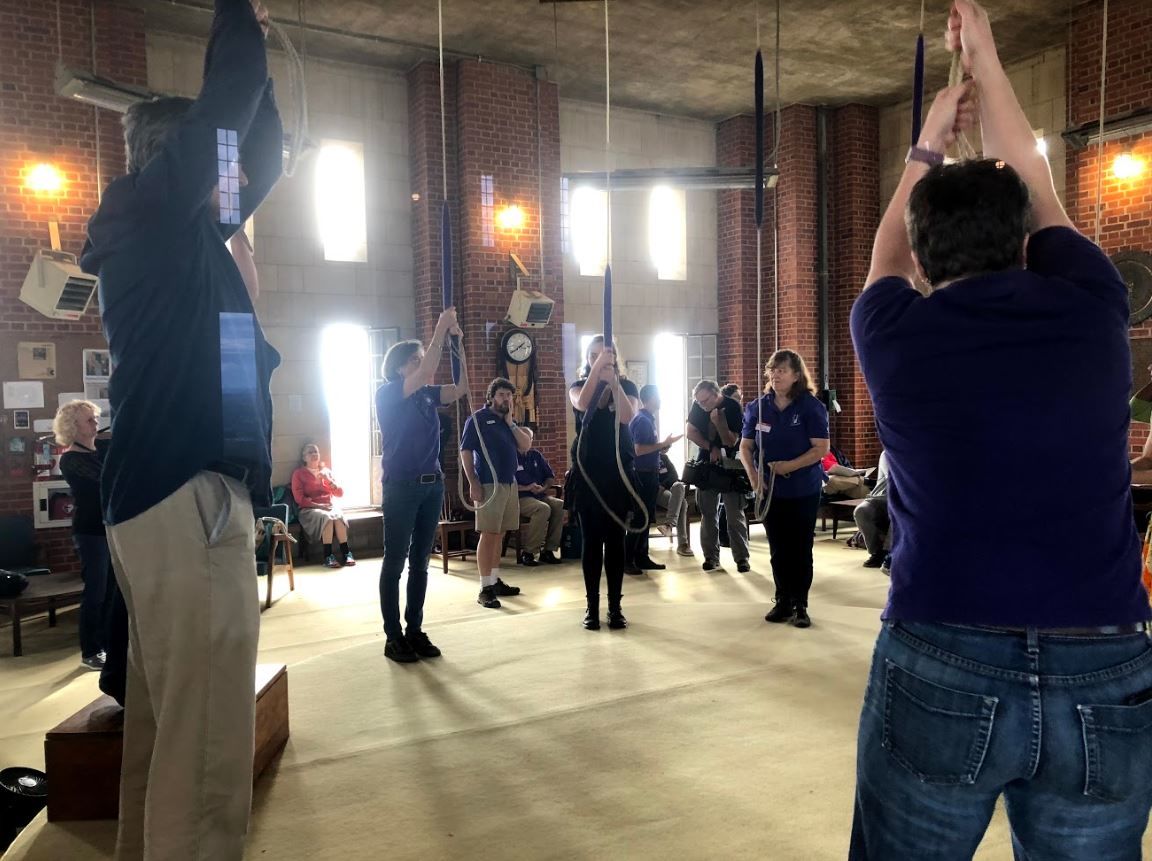

WASHINGTON — If you heard bells ringing for longer than usual Saturday at the Washington National Cathedral, it’s because of the nine teams of ringers from all across the continent showing off their “change-ringing” in Northwest D.C.

Change-ringing is the art of producing musical patterns from the bells’ different sounds and pitches while ringing them. The Washington National Cathedral’s carillon, or set of bells, includes 53 bronze bells that the ringers operate on the building’s 31st story.

Do they need sheet music? Not according to Beth Sinclair of the D.C.-based Washington Ringing Society.

“The bells are not conducive to ringing music, because they ring once with each rotation,” Sinclair said. “What we ring are permutations of the numbers, which translate into patterns in our minds while we’re ringing.” She likened it to everyone playing a different note of a tune.

Forty years ago, Sinclair learned change-ringing as a student at the National Cathedral School. She is one of the performers at the competition Saturday.

Three of the nine teams competing were fielded from the Washington Ringing Society. As the group’s area representative, Sinclair coordinates with ringers from around the world; she even fielded two emails Saturday alone from ringers who will be visiting D.C. in the coming weeks and want to practice with the society.

“If you are a ringer, you can dial up someone who is in another city if you’re going to be visiting … and they will welcome you,” Sinclair said. “It’s a completely transferable skill.”

Sinclair said there are ringers from all over the country and the world, and Saturday’s competition was no exception. She said there were individuals from Indiana, Toronto and Seattle, and entire groups of performers from Boston, New York and Delaware, performing in the competition Saturday.

The competition will be judged solely by Mark Regan, ringing master at Worcester Cathedral in England.

Regan alone will select the winning team after hearing them all perform. Each piece will lasted about eight minutes or so, after which Regan will judge each team’s performance and give them feedback.

He said while ringers practice and prepare extensively, a lot of the actual performance comes down to “fate” in the moment.

“You’re controlling fast-moving bits of metal to split-second accuracy using a long rope, so I’m looking at timing, accuracy, punctuation, rhythm … I can pick up the teamwork and how mathematical accurate the performance is,” Regan said on how he judges the performances.

Sinclair’s comments supported how difficult it is for even experienced teams to win.

“You have to get lucky and have everything go perfectly right, but everyone has the potential to ring really well,” Sinclair said.

In such a difficult competition, what does the winning team actually get?

“The prize is being first, and ringers are very, very competitive,” Regan said. “And this helps our art carry on every year.”

Marie Dal Corso, a D.C. resident formerly from Malta, said she and her husband started change-ringing lessons at the Washington National Cathedral in March after moving to the area last year.

“It takes a huge amount of focus,” Dal Corso said of change-ringing. “It’s really unforgiving, the timing of it.”

Dal Corso said her interest in change-ringing stemmed from her childhood. She said she grew up with the sound of church bells in every village in Malta, and said the church was “the focal point of everyday life” there.

Mary Clark from Arlington, Virginia, has been a bell-ringer for 49 years.

“It’s a mental exercise for someone my age,” Clark said.

But Clark said the mental preparation is only half of it; the rest is physical, since operating the bells takes such a toll. She recommends lifting weights to prepare.

WTOP’s Mike Murillo contributed to this report.