Nearly a quarter century after its closing, WTOP looks back at D.C.’s legendary Duke Zeibert’s restaurant — a place where Washington’s elite and celebrities from across the world came to see and be seen, but most importantly experience something they’d never forget. In Part 1 of “Duke Zeibert’s,” WTOP chronicles how a kid from upstate New York would come to reign over a mix of elites from business, sports, politics and show business.

WASHINGTON — Why should anyone care about a restaurant that closed 24 years ago?

In the case of one Duke Zeibert’s, it’s because the restaurant holds a unique place in the history of the nation’s capital — and, to an extent, a unique place in the history of the nation.

As D.C.’s elites return to resume fall business, they’ll be power-lunching at places too numerous to list — places such as Cafe Milano, The Palm, Capital Grille, BLT Prime and so on.

But back before the D.C. dining scene became so rich and diverse, the elites met in Duke’s dominion. For over 40 years, it distinguished itself as the power lunch spot in a city whose main export is power. It brought together politicians, businessmen, celebrities and, of course, average D.C. folks who just wanted to grab a bite and chew the fat.

The story of Duke and his namesake restaurant is one of hard work, boldface names and a D.C. that once ate (and drank) together, even when they didn’t necessarily agree — a practice that might serve D.C. well today.

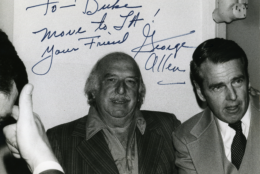

(Courtesy Historical Society of Washington, D.C.)

“It was a place to hang out, to talk, to talk politics, to talk sports,” said broadcast giant Larry King, who was a regular at Duke’s. These days, he’s the host of Ora.tv’s “Larry King Now” and “Politicking With Larry King.”

Duke Zeibert’s was also a place where history was made — like that time a CBS Sports personality imploded his career on camera; the time Yankee legends teed off on L Street; and the moment jazz royalty got some bread (the green kind) from an unlikely source.

Presiding over all these moments was a colorful man whose charisma rivaled that of the movie stars he hosted. Duke was the literal host with the most. He worked the room with corny one-liners and a personable handshake or pat on the back.

Zeibert served (and befriended) presidents, movie stars and sports legends. Duke Zeibert, however, knew being a good host wasn’t just about catering to the autograph-signers. He dished out hospitality to celebrities and working stiffs in equal portions, King said.

But on an average day, it was Duke’s regulars who brought the restaurant to life.

Jack Kent Cooke: The Redskins owner at the time always got his favorite table. Duke loved the Burgundy and Gold so much that, beginning in 1971, he took cake and ice cream out to the team’s training facility on Thursdays after a win. The franchise’s Lombardi Trophies were even on display in the restaurant.

Larry King: The broadcasting legend used to sign off from his Arlington-based radio talk show by saying he was going to Duke Zeibert’s, as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington played him out. “I loved him as a man,” King said of Duke. “He was like a second father.”

Larry L. King: Author of “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.” Confusion over reservations once prompted Duke to order staff to ask whether “Radio” Larry King or “Whorehouse” Larry King was making a reservation.

Bob Strauss: The former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, who also was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, craved the atmosphere — so much so that it could get on Duke’s nerves.

And then there were the local journalists who came back time and again to eat and drink off the classic American menu filled with ethnic accents: chicken or beef in a pot, seafood, goulash, matzo ball soup, etc.

They included Chuck Conconi, whose career included work at The Washington Post, Washingtonian magazine and WMAL radio; William Regardie, the editor-in-chief of Regardie’s Magazine; and longtime sportswriter Morris Siegel.

For journalists or any other curious listener who considered themselves on the clock, being nearby as alcohol and business mixed could yield its own buzz.

“The good news about the drunks — well, they would spill the beans,” said David Adler, the CEO and founder of BizBash media. His old magazine, Washington Dossier covered “the human side of power.”

In the era of the three-martini lunch, the darkly lit bar was its own center of influence. Its placement inside the restaurant offered seclusion to day drinkers, salesmen and other professionals with time to kill.

“Somebody could be in our bar at the old place and no one would even know they were there,” said Randy Zeibert, who worked for his father through the years. “A lot of them were [Post] photographers that were on call. Of course, half the time they would get calls [at the restaurant], they would say, ‘Tell them I’m not here.’”

The original Duke’s was done up in blue and brown hues. On the walls, large caricatures of a smiling Duke playing various sports smiled down. Adler likened it all to a school cafeteria where the jocks, nerds and other cliques had their own areas but still mingled.

It was all fit for “Radio” Larry King, who started haunting the place in the ‘70s. But there was more to the joint’s appeal, he said. Duke’s place was a community.

For the insiders, membership had its privileges. Conconi recalls a time when Duke discreetly stopped by during his meal. The table next to his was empty, and two of Conconi’s bosses — Post Executive Editor Ben Bradlee and Post Style Editor Shelby Coffey — were waiting to be seated. Duke sensed that it might be awkward for a regular to be dining so close to his bosses.

“‘Would it bother you if I sat them there?’” he recalled Duke asking. “I said yes, so they had to wait for another table to be free.”

He was careful like that, Conconi said.

The pecking order

Choice tables weren’t just dished out. Duke had a way of sensing who was up and down in This Town, and it was expressed in where those people were seated. Elisabeth Bumiller said it best in 1980, writing in the Post: “Duke not only reflected the town’s pecking order; in some ways, he helped define it.”

Clout helped, sure — but so did loyalty and notoriety.

Post senior editor Marc Fisher wrote in 1995:

“At Duke’s, there was order to the world. A pecking order that Zeibert neither imposed nor enforced. Instead, with heavy pats on the shoulder, sotto voce jokes and an impeccable sense of propriety, he inhaled the true order of things and then put his customers in their place.”

Mixed-seating arrangements inspired another quintessential D.C. specialty: speculation.

“If [former Kansas Sen.] Bob Dole was eating with somebody, you knew something was going on,” Adler said.

Duke’s “top-shelf” clientele were kept in the front of the restaurant. Average joes were more likely to end up in the back area, also known as “Siberia.”

(Duke’s former manager, Mel Krupin, described how seating was handled in a 2008 interview with Washingtonian magazine.)

Make no mistake: Few, if any, wanted to eat in Siberia.

Take the time, for example, when writer Nora Ephron was ushered back there with a lady friend during the Watergate era. As related by the Post’s Lois Romano in 1982, Ephron noticed that a particularly newsworthy boy’s-club crowd was getting all the good tables.

“Exactly what do you have to do to get a good table in this place?… Be indicted?” she snapped.

When Conconi was writing the Personalities column for the Post’s Style section in the 1980s, he frequented Duke’s to hunt for material. He was among the selected few who were higher up in the pecking order.

At the top, he said, were Cooke and King.

The host with the most

What made Duke’s so successful was the personable man behind it.

“The worst thing a guy can do is put his name on a restaurant sign,” he told The Washington Star’s Sandra McElwaine in 1986, some three decades after he went into business. “Then you become a slave; everybody comes to see you and wants you to come over and say hello, impress their boss.”

He had a point. The restaurant was really all about Duke. In part, because Duke was all about the restaurant.

Born in 1910, the Troy, New York, native got his start working at resorts in the Catskills and Berkshires. He later worked for the restaurant chain Fan and Bill’s in Florida, where he learned some valuable lessons about stature, as he told The Washington Star in 1972:

“I was a very popular guy. I was invited everywhere … on yachts, parties, estates, people catered to me. Until I had a run-in with my boss and left the place. In two weeks’ time, I noticed no one bothered with me anymore. I learned the lesson very early … it wasn’t me, it was my position that made me in demand.”

Miami is also where he got the nickname. He had taken to wearing white silk pants on the job.

“The other waiters made fun of me,” he once told The Associated Press. “They kept asking me, `Who do you think you are, a duke?’ I was suddenly `The Duke.’”

The war and gas rationing helped end Duke’s itinerant existence, and he settled in D.C. In 1950, he went into business for himself, opening his iconic restaurant in the old LaSalle Building.

It was located near the intersection of Connecticut Avenue and L Street Northwest. (The Washington Square building stands there now.)

“When people came in the restaurant, they wanted to be recognized, and Duke was very good at that,” said Randy.

A few other things about Duke that are important to know:

- He was plugged into the scene, whether it was politics or sports. “He knew what’s happening. He knew what was going on,” King said.

- He loved gambling. Whether it was Vegas, Atlantic City or Pimlico, the man was all about the action.

- Suffice it to say he dated around. He was divorced three times, “and two of them didn’t count,” he told McElwaine. The third marriage was by far the most successful — 20 years, with the mother of his three children.

Duke’s longest commitment was not to a woman, but to the restaurant and the guests who dropped in — including the celebrities who made history there.

‘Youze Guys’ and other boldfaced bon vivants

Get enough big shots in the same place, and the stories write themselves.

Zeibert would tell of one time, for instance, when then-Vice President Richard Nixon had signed a check for a meal, prompting a waiter to ask, “Is this guy any good?”

Bobby Kennedy was also known to kick back there. “[Duke’s] was really hot during the Kennedy administration because the Irish loved to drink, and his bar was always pretty crowded, especially at cocktail hour,” said author Warren Adler, who frequented the place back in the ‘60s. (Duke was close enough to the Kennedys that he visited JFK at the White House and was on RFK’s funeral train in 1968.)

Another immortal name that frequented Duke’s, albeit briefly, was NFL legend Vince Lombardi. In 1969, he took over a Redskins team that had gone 5-9 the year before. As coach and general manager, he took them to a 7-5-2 record months before his death. The team had offices nearby, and Lombardi brought coaches over for dinner at least once a week.

Randy recalled when he tried offering a draft-pick suggestion to Lombardi. “‘You gotta draft this guy from Syracuse,’” he told him. Then the realization of talking to Vince Lombardi got the best of him.

Harry S. Truman holds the distinction of being Duke’s favorite all-time customer. “What a man’s man he was,” Duke told the Star in 1980. “A real two-fisted guy.”

Jimmy Hoffa would sometimes lunch there at the same time as then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. During one noteworthy lunch in 1965, the labor leader slipped William James “Count” Basie $3,000. According to the Post, union objections had prevented the jazz legend’s band from playing a benefit (which also featured Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald) unless they got paid. Hoffa covered it.

And then there were the New York Yankees. One time in the early ‘60s, the pinstriped titans were in town to play the Senators. Duke, who was hanging out in RFK’s press box during the game, invited “youze guys” in the press box.

“So all the Yankees sportswriters — and then Mickey Mantle — we all showed up at Duke’s about midnight,” Regardie remembered.

Their rowdy night ended with some golf.

Mel, Randy, et al.

Duke’s gregarious nature, combined with the 400-plus seating capacity, meant delegating some authority. He employed a staff of dozens, and they were colorful in their own right.

Victor “Man o’ War” Friedman, for instance, would ask for tips upfront so he could play the daily double at the track. Another guy on staff was 72 when he accepted Redskins great John Riggins’ challenge to arm-wrestle. (Riggins, then 38, beat him twice, but it reportedly wasn’t easy.)

Randy worked there from the early ‘70s through to the restaurant’s final closing in a variety of capacities, including manager.

Also helping out for over a decade (1968–1980) was Mel Krupin, a big guy from Brooklyn who liked cigars, kept a switchblade on a gold chain and didn’t suffer knuckleheads gladly. (Mel once told someone who asked for a table to try Marlo Furniture.) He dealt with the union and even helped at times around the kitchen, where he was no slouch — he had studied to be a chef in New York.

The End (kinda)

But the staff, the celebrities, the regulars or the Duke himself could not keep a bustling Zeibert’s from closing.

The LaSalle Building was getting knocked down and the tenants had to vacate. A new mixed-use complex was going up amid an era of new development around the District.

On April 30, 1980, the night Zeibert’s would close its doors, Duke told Bumiller:

“‘I never realized the impact this restaurant made on the city of Washington. This restaurant’s had soul. But no, I’m not going to make the mistake of trying to reopen the place and recapture it. You can never do it again.”

There was good news, though: longtime employee Mel Krupin wanted to start his own restaurant, and Duke told folks to look for his manager to pick up the torch and open up a new joint where the crowd could resume its rituals.

The last night at Duke’s wasn’t unlike others — rowdy. Bumiller wrote:

“As the hours wore on, the mood … went from weepy sentiment to drunken gaiety to weepy sentiment and maybe back, depending on how long you sat at your table and how many drinks you had.”

A more-succinct eulogy was penned by Mo Siegel in the Star:

“Duke Zeibert’s classy L Street joint, which had been on real estate’s death row for months, was terminated last night. The lifeline was severed in a heavy cascade of scotch, bourbon, vodka, gin, beer and wine. There was also coffee, tea and Perrier for those who treat wakes disrespectfully.”

Former House Speaker Tip O’Neill was there that final night, as was Carl Bernstein, The New York Times’ Bill Safire and ABC’s Sam Donaldson.

So was President Carter’s White House counsel, Lloyd Cutler. He usually ate lunch at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., Bumiller wrote, so his experience at Connecticut and L was somewhat less-exclusive.

He sat in Siberia.

The curtain had dropped on a D.C. institution, but what was supposed to be The End turned out to be just an intermission.