Nearly a quarter-century after its closing, WTOP looks back at D.C.’s legendary Duke Zeibert’s restaurant — a place where Washington’s elite and celebrities from across the world came to see and be seen, but most importantly experience something they’d never forget. In Part 2 of “Duke Zeibert’s,” WTOP chronicles Duke’s short retirement, a second location, choice anecdotes, some awkward competition and why it all ended.

WASHINGTON — In 1980, a new development at Connecticut Avenue and L Street meant the end of both the LaSalle building and its beloved tenant, Duke Zeibert’s restaurant.

It also meant retirement for its namesake restaurateur, and it set adrift a crowd of power-lunching regulars, who were a veritable who’s who of business, politics, sports and entertainment.

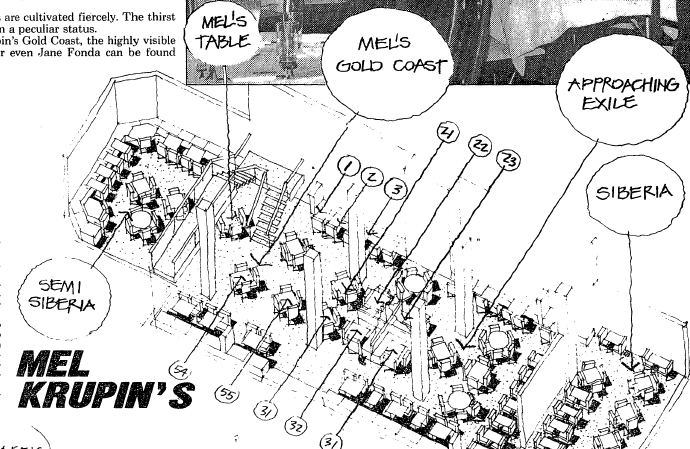

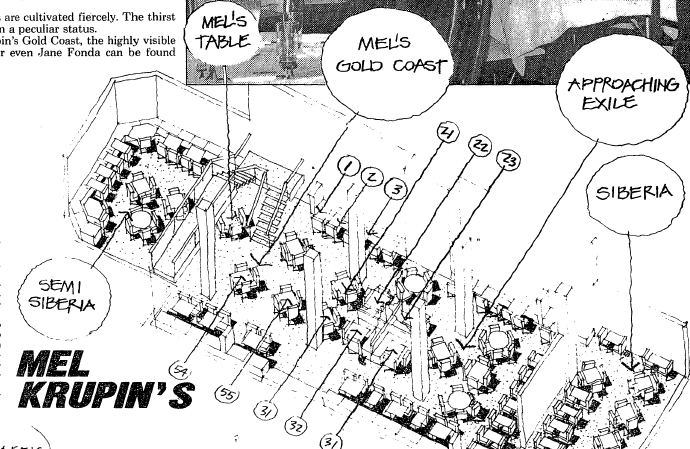

But there was hope: A familiar name was going into business for himself. Mel Krupin, who had toiled tirelessly as Duke’s manager for over 11 years, opened his own restaurant on Oct. 20, 1980, not far from where Duke’s had closed months earlier.

Mel’s time had finally arrived. He could step out from a giant shadow and claim his own dominion.

Mel Krupin’s was another classy space, just up the block from where the LaSalle Building was being knocked down.

The Duke’s faithful wouldn’t have to wait long to resume their familiar rituals, ordering from a familiar menu, served by some familiar faces: About 60 of Mel’s former co-workers were joining him. Chuck Conconi, veteran D.C. journalist, said it was the realization of Mel’s dream.

While Mel had gained his own dominion, he was gaining a new customer, too — Duke Zeibert himself. Now retired, Duke was rubbing shoulders with the same crowd as a fellow customer, and he had more time to golf, play the ponies and enjoy his twilight years.

It turned out to be a disappointment. As Randy Zeibert remembers, retirement just wasn’t for his dad, even though Duke was in his early 70s. Compared with the thrills of the daily lunch rush, a life of pure leisure was for the birds.

Or as Duke himself told USA Today’s Karen De Witt:

“‘The whole thing is that being retired is not very meaningful,’ says Zeibert. ‘I mean, I like golf and bridge and hanging out in Las Vegas, but I was chasing young girls and when I caught them, wondering what I’d chased them for. Being retired was a meaningless life.’”

Washington Square

Duke’s drudgery went on as Washington Square was being built a block away. The 1-million-square-foot office/retail property, which would open in 1982, included a restaurant space. The developers didn’t have a tenant yet. The rumors started: Duke’s might open up again.

Mel caught wind of it, too. Would Duke come out of retirement and open another restaurant?

William Regardie, former editor-in-chief of Regardie’s magazine, said he was the one who broke the news to Mel, who had called one morning in the early ’80s to ask one question: “Is it true?”

It got worse: Many of the people who had followed Mel in 1980 were quitting to work again for their former longtime boss.

Duke Zeibert’s second location opened at noon, appropriately, on Aug. 15, 1983. The modern space featured an outdoor terrace overlooking Connecticut Avenue. Randy, his son, helped manage, and Duke was holding court once again.

It was an era when the complexion of D.C. was changing, with other new developments sprouting up around the District at a brisk pace. Duke’s, by contrast, offered some familiarity, a slice of old D.C., served on nice new china.

(For video of that new location, check out this C-SPAN footage of a 1993 party Larry King threw for then-Vice President Al Gore and his family.)

The new bar didn’t have the same dark seclusion desired by day-drinking professionals as the old Zeibert’s, but it didn’t matter to the business community and other regulars. Those who had moved on to Mel’s or other joints were now returning to that old block south of L Street.

It was hurting Mel’s business. “You couldn’t have two restaurants less than a block away from each other,” Conconi said. “… Essentially, they had the same menus.”

‘The Great Pickle War of Connecticut Avenue’

Weeks before the new Duke’s even opened, The New York Times had christened the competition-to-come as “The Great Pickle War of Connecticut Avenue.”

While it made for great reading in the papers, it was serious stuff to the two guys trying to run their respective businesses. Mel felt betrayed. Duke had no ill intentions — he just wanted a return to the life he loved.

There was some back-and-forth sniping, with the nadir perhaps being a 1986 John Ed Bradley feature in The Washington Post Magazine. It got personal. Two choice passages sum it up:

“This is the thing Duke is saying: Mel treated celebrities like precious metal, stroking them real good and doing doing doing, but your regular not-so-famous customers he treated like hamburger meat.”

…

“Now, hearing Duke’s side of the Mel Situation, Mel himself points at a spot below his shoulders. Mel says Duke planted a knife in that spot and has blood on his hands.”

Looking back at Duke coming out of retirement and its effect on Mel’s place, Randy Zeibert takes exception to the media characterizing the situation as a feud.

For the longtime Duke’s faithful who had moved on to Mel’s, The Pickle War made for an awkward dynamic.

Some tried to keep both sides happy, at the risk of losing out on good tables.

David Adler — the CEO and founder of Bizbash media and former CEO of Washington Dossier magazine — went to both Mel’s and Duke’s. “But then you’d have to make sure that you were doing it secretly,” he said, “because you didn’t want to piss off Duke or the other way around. You had to choose your alliance.”

In the end, Duke won the war. Mel Krupin’s closed in 1988. Mel later went on to run a deli with his brother in Tenleytown. It drew its own cast of dedicated regulars, and closed with the brothers’ retirement.

Duke tried to reconcile through the years, Conconi said, but Mel declined.

(Attempts to reach Mel Krupin, who still lives in the area, were unsuccessful. This wise-guy reporter is happy to buy him lunch and talk about whatever — on- or off-record.)

Duke’s Second Act

Those who went to the new Duke’s had, on a few occasions, a unique vantage point on history — or something resembling it, anyway.

Gorby finally walks in

In 1987, the Cold War was thawing into a warmer camaraderie between the two superpowers, and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was in town Dec. 10, 1987, for a summit. His motorcade was headed southbound on Connecticut Avenue, already late for a meeting with President Ronald Reagan.

At the intersection with L Street, Gorbachev stepped out of his limo and started shaking hands with passers-by. It stopped the motorcade, horrified his security and stunned the lunch crowd at Zeibert’s. Here was a world leader staying true to his brand of openness.

”Waiters and customers rushed to the balcony,” according to the Post. ”Gorbachev looked up at the expense-account crowd and waved. The 40 people on the balcony and the crowd on the street burst into applause.”

Duke rushed out and invited him to lunch. “We have borscht!” he yelled. Gorbachev had other plans. He eventually re-entered the limo, and the motorcade resumed rolling toward the White House.

Six years later, Gorby finally dropped by Duke Zeibert’s. He was in town for an interview with Larry King, and as Larry would do with guests, he took him to Duke’s beforehand.

“He wore suspenders,” King recalled. “Came up that escalator that went straight up. … Duke had a great time. In fact, Duke looked at me and said, ‘Who could believe this?’”

Jimmy the Greek’s fall

It was Jan. 15, 1988, two days before the Redskins were to host the Minnesota Vikings in the NFC championship game. The CBS studio crew was in town, and Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder, who would give viewers gambling advice before kickoff, was at Duke’s eating lunch. NBC Washington reporter Ed Hotaling was also there, interviewing diners about Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday.

“I went over to Jimmy,” Randy remembered, “and said, ‘Do you mind if so-and-so interviews you for Martin Luther King’s birthday?’ He was happy to do it.”

What followed was the 1988 equivalent of a racist tweetstorm. Snyder mused aloud about black coaches in the NFL, and expressed concern that “there’s not going to be anything left for the white people.”

Snyder apologized, but it was too little, too late. He was fired from “The NFL Today.”

Randy Zeibert considers it one of the restaurant’s worst days. “It didn’t work out for him,” he said.

The lonely ambassador

Bob Strauss, a Duke’s regular and former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, had been appointed U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1991. The position’s title later evolved into ambassador to the Russian Federation.

Apparently, the Moscow resident would’ve given anything to be in “Siberia,” Duke’s less-premium seating area. “He was bored to death as ambassador,” recalled Conconi, who was there a couple of times when Strauss would call in just to see what was going on at his favorite hangout spot.

Regardie remembers stepping in to answer one such call during a busy lunch rush, much to Duke’s chagrin.

Strauss’s lot improved in November 1992. He returned to the states after a young Arkansas governor was elected to the White House. Months later, Strauss played the diplomat yet again, orchestrating a bipartisan dinner at Duke’s between President Bill Clinton and Sen. Bob Dole, then the minority leader.

The End (for real this time)

It was the same day that Clinton was elected president — Nov. 3, 1992 — that a new restaurant opened off Wisconsin Avenue in Georgetown. Cafe Milano offered convenient parking across the street, private dining rooms, a cozy ambiance and a decidedly more-modern menu.

It clicked with the elites, drawing its own eclectic mix of boldface names — and excelled in the dinner, alcohol and weekend business that eluded Duke’s.

“Cafe Milano is what the social set’s been hungering for,” reads a Post headline from December 2002.

It’s not the only reason why Duke Zeibert’s Washington Square location closed on June 30, 1994, but it illustrates some reasons why. Tastes were evolving, and the competition was stiffer: Milano was among many new places appealing to an ever-growing set of diners with more-refined palates.

“They were disrupted, like everything else. It was too old school,” Adler said.

Reflecting back on that day, Randy just remembers sadness. The mood, he said, was nothing like the first location’s closing. “In 1980 it was more of a party,” he said. “… In 1994, it was probably more of a wake.”

That Washington Square space was vacant for a while. Then, in January 1997, Morton’s Steakhouse opened up and remains there today.

About seven months later — Aug. 15, 1997 — Duke Zeibert died at the age of 86 in his Bethesda home.

Even though Krupin never reconciled with his boss-turned-competitor, he offered a fitting tribute in Duke’s New York Times obituary: ”Our quarrel is no longer important. What is important is that Duke Zeibert was a great restaurateur and the city misses him badly.”

With the closing of Duke’s, D.C. itself lost “a sense of reality, a sense of who the city was,” Conconi said. “Washington is an odd town. It doesn’t really have, you know, real neighborhoods like, say, New York or Chicago or Boston or cities like that.”

The man and his namesake had engendered community in a town that needed it.

D.C. lost something else, too, something that feels especially apparent in this nation’s modern tribalist climate.

“I think some of the life and sense of humor of the national capital was lost when he retired and now even more so that he died,” Strauss said in the Post’s obituary.

###

Randy and Audrey Zeibert are retired now and living out west. He’s about the same age Duke was when he retired the first time. Fortunately, it agrees with him.

As much as Randy loves living in Las Vegas, life is a far cry from the time he walked through Yankee Stadium with a retired Joe DiMaggio, or that time he suggested a draft pick to Vince Lombardi. He looks back on those days with wonder.

“Because of Duke … every place I went or even in school, I was treated special. Not that I personally deserved it, but because of Duke.”

And why not? His dad was a celebrity in his own right, a larger-than-life presence who once made a workday lunch an event.

“The front person really, really mattered,” Conconi said, “and that’s why Duke and Tommy [Jacomo, longtime maitre ‘d at The Palm] were both just brilliant at it. Not only were they brilliant at it, they loved it. They were performing when they came on, it was a performance every day. It was like, the curtain up — here we go.”

The show is but a memory now, and perhaps a curtain call is in order. Duke was a bona fide institution, so he gets the last line.

“Some people say ‘Duke Zeibert’s an institution.’ I’ve only been here 50 years,” he told C-SPAN in 1993. “… A crazy house is an institution, too.”

Special thanks to the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., for their assistance with this series.