WASHINGTON — While social media users post “drain the swamp” jokes about the small sink hole on the north lawn of the White House, most in D.C. aren’t aware of the process in place — and manpower required — to protect the National Mall from 100-year flooding.

Visitors to the Mall in the past four years have likely driven past the stone walls of the Potomac Park levee, unaware of its purpose and what steps would need to be taken before it could protect the Federal Triangle, well as low-lying D.C. neighborhoods from coastal storm surge and river flooding from the Tidal Basin and the Potomac River.

Drivers on 17th Street NW drive through a 140-foot gap in stone walls in place on the grounds of the Washington Monument and the World War II Memorial.

Many visitors assume the stone walls are part of the monuments they flank — instead, they’re part of the 12-foot-high earthen berm that runs along the northern edge of the mall.

Earlier levees outlived their effectiveness.

The original system was Congressionally authorized to provide risk reduction for a flood event up to 700,000 cubic feet per second on the Potomac River from river and storm surge flooding. The project was completed in 1939 and relied on sandbags and earthen fill to form a temporary closure across 17th Street, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

A 2006 storm flooded the National Archives, the Internal Revenue Service, Commerce Department, Justice Department, and several Smithsonian museums.

In January 2007, the Corps determined the closure structure was unreliable and gave the system an unacceptable rating. That led FEMA to “de-accredit” the levee, which prompted much of D.C. to pay into the National Flood Insurance Program.

The current levee and closure system “reduces risk to human safety and critical infrastructure downtown,” according the Army Corps.

If 100-year-flooding were expected, the National Park Service would have to truck in and install aluminum panels to bridge the gap and protect low-lying areas from devastating floods.

“The equipment is stored at Brentwood (maintenance facility), on trucks, and is ready to go,” said Mike Litterst, chief of communications of the National Mall, for the National Park Service.

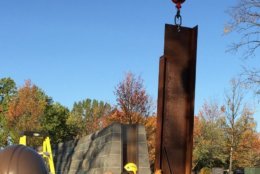

After the half-hour trip to downtown D.C., the aluminum panels would be connected to steel poles and inserted in permanent grooves built into the steel walls.

“Once the trucks get to Constitution Avenue, it takes about four hours to get the walls up,” Litterst said.

Since the levee is only a few years old, conditions have never warranted its use during an actual storm.

“Deployment isn’t going to come as result of heavy rain, or a tornado,” Litterst said. “Those are quick-moving.”

The threat from Potomac flooding is slower to develop, more predictable and easier to track Litterst said.

“We have gauges in several places up river that are monitored by the Park Service and Army Corps. If it were to reach a certain level, we’d start the process,” of assembling the levee he said.

“I checked on Friday, after the recent rains, and we were nowhere near the mark we’d have to reach.”

Flooding along the Potomac generally runs down river, from west to east, and takes several days to reach flood points near the National Mall.

“If a nor’easter were coming, we’d have forecasts before it comes in,” Litterst said. “If the flooding comes to Harpers Ferry (West Virginia) we’d have about 36 hours before it reached us.”

Still, since a man-made intervention is required to head off floodwaters, the Army Corps mandates annual testing of the levee.

“With new people coming in, you want them to get periodic ‘hands-on’ the equipment,” Litterst said.

The most recent testing took place in fall 2017.