WASHINGTON — The national tumult of 1968 was marked by iconic images, including the campus takeover — students occupying critical campus buildings and shutting down institutions for days.

The Columbia University takeover in April of that year was the best-known, but it appears the first one happened in D.C. 50 years ago this week.

About 1,000 students at Howard University took over the administration building, leading to the shutdown of the school from March 19 through March 23, 1968.

As the anniversary approached, two leaders of the protest — Adrienne Manns Israel (then Adrienne Manns) and Anthony Gittens — spoke with WTOP in separate interviews about how the demonstration unfolded, why it happened and how it affected the rest of their lives.

In addition to these interviews, the events have been reconstructed with the use of contemporary accounts from The Washington Post and The Washington Evening Star, as well as the 1987 documentary “Eyes On the Prize” and the 1968 public television documentary “Color Us Black!”

‘A joyous coup’

It was far from the first protest at Howard. The takeover was the result of months of planning and years of grievances, the two organizers said.

Gittens, now the director of the D.C. International Film Festival, said that “There was a number of demonstrations at Howard when I was there, some of them I was involved in.” Then, with a laugh, he said, “most of them I was involved in.”

The decision to demonstrate wasn’t an easy one for Israel: She was on a scholarship and couldn’t afford to lose it, but she said now “I knew that it was possible.” She decided the risk was worth it “because of the implications for our future, as well as our community.”

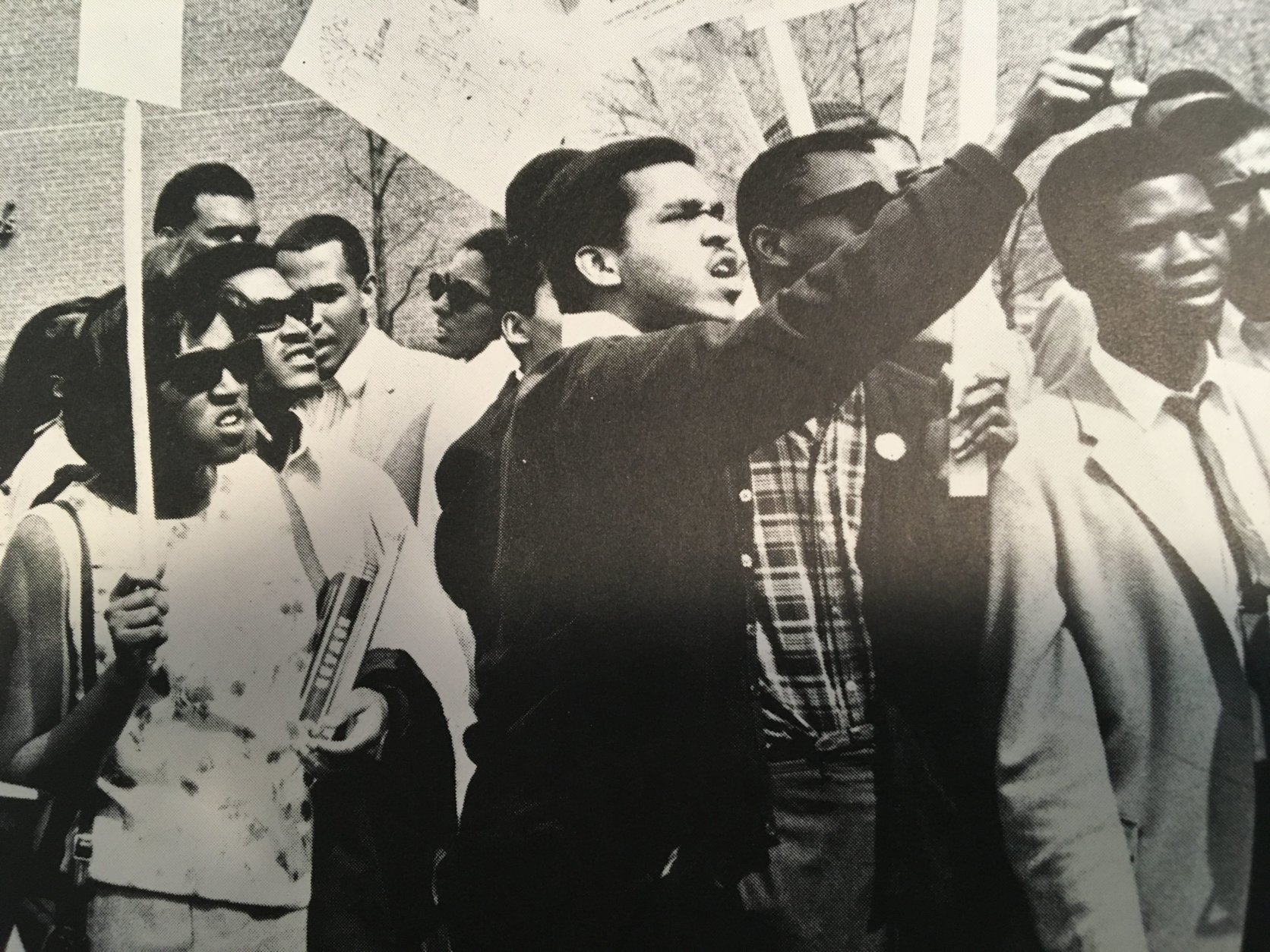

On Tuesday, March 19, 1968, about 1,000 students held a rally in front of Douglass Hall. From there, a group of students entered the administration building.

The next move was to conduct a sit-in at President James Nabrit’s office until their demands were at least addressed, if not met.

The activists wanted Nabrit’s resignation; a judiciary system for student discipline; an emphasis on African-American history and culture in the curriculum, and the dropping of charges against 39 students inspired by the above issues who had made a protest three weeks earlier at Howard’s centennial Charter Day celebration.

Most important, Israel remembers now, they simply wanted negotiations, and to be heard. That was unusual at most institutions at the time, and particularly at Howard: “They would not dignify us with a response,” Israel said. “Our demand is an answer – we want you to say publicly what you think about these issues. And [Nabrit] never would.”

As they entered the building, it turned out they had more support than they thought.

“When we went in, we thought it would be the usual group … that we would be there, and it would be one more instance when they came and dragged us out,” Gittens said. “We turned around as we were walking into the building, and first there were scores, and then the word got out around campus about what was happening, and there were hundreds of students who joined the protest and took over the entire building.”

“We thought we had enough people to fill the third floor,” Israel said, “… but there were so many students who came into the building … we had to adjust.”

The only people they let in were guards who locked the other offices in the building. And when public relations director A. Alexander Morisey tried to enter Wednesday, March 20, he was stopped by a line of students stood shoulder to shoulder, the Evening Star reported. One told him, “This is the revolution.”

Security guards went from classroom to classroom, locking the doors and telling students and professors that the university was closed. The medical buildings remained open, however.

The Washington Post described the gathering as “a huge, noisy picnic” and “a joyous coup.” Gittens remembers a “calm atmosphere.”

The scene is captured in the 1968 public-television documentary “Color Us Black!” Speakers included Gittens and Israel, and there was lots of singing – including an adapted version of “Down By the Riverside” – and a ubiquitous chant:

Beep Beep

Bang Bang

Ungawa

Black Power

But the students also meant business. When Ewart Brown, one of the leaders, was asked about the prospect of administrators sending police to retake the building by force, he said that if that happened, “We will react accordingly. …

“No cop’s going to whip our heads. I hope the [D.C.] police understand that.”

‘The black Harvard’

The changes to the disciplinary system were critical, Gittens remembered: “If they decided that a student was … committing something that was unbecoming of a Howard student, they had the full authority to put you out. With no trial, no hearing, nothing.”

That didn’t sit well with many students, and it particularly rankled Gittens: “As someone who had to work to get money to go to school, I wasn’t a child anymore.”

But there was a more fundamental problem: Despite a student population that was at least 90 percent African-American, a common refrain among the protesters was “Howard is not a black university.”

By the 1960s, half of America’s black doctors and a quarter of its black lawyers were Howard graduates. The university was called “the black Harvard.”

But the curriculum wasn’t reflective of the students – there were no courses on black history. The theatre department didn’t do works by black playwrights. No jazz, blues or gospel performances were allowed in the fine arts building.

Virtually no black writers were taught in the literature classes, even though “we had some of the foremost people in the field teaching there,” Israel remembered. “Sterling Brown, Arthur Davis … There were all kinds of teachers there who were equipped, and we could have had a robust program.”

Nabrit, the university president, had been quoted as saying that he wanted Howard to admit more white students. Around this time, the trustees released a statement saying in part, “Howard is not destined to be a black university.”

The activist students at Howard considered that unacceptable. Michael Harris, the president of the freshman class, said in the “Color Us Black!” documentary, “Howard University should serve another purpose other than preparing people to fill slots in white society.”

By March 21, the third day of the protest and second of the shutdown, Lorimer Milton, the chairman of the board of trustees, told the Washington Evening Star that he didn’t know when the university would reopen, but that “When it does reopen, it will reopen for students who want to go to college and not for students who want to sit in the administration building.” He added that the university was looking to see what legal action could be taken.

Protesters in the administration building had grown to about 1,200, the Evening Star estimated, adding that students were rotating in and out of their dorm rooms to freshen up, and plates of food were being brought in.

The university also announced that all students had to be out of the dorms by the following day. That didn’t endear them to the parents who had to drive, in some cases over rather long distances, to retrieve their kids.

A father from Hartford, Connecticut, who had to take the day off to head to Howard said, “I haven’t been able to talk to anyone from the administration. All I can talk to are students, and now I’m against the administration and with the students.”

‘The black man’s battleground’

The civil rights documentary “Eyes On the Prize” claims that one of the seismic events on the campus was the successful campaign of Robin Gregory for homecoming queen in 1966. She had an Afro — a natural hairstyle that was modest by today’s standards, but jarring to those used to processed, straightened black hair.

From there, a black-awareness movement grew: In 1967, Gen. Lewis B. Hershey, director of the Selective Service was booed off the stage at Howard, with one protester shouting “America is the black man’s battleground.” And earlier in March 1968 came the Charter Day protests. It didn’t take long, however, for the movement to bump up against some of the more established features of Howard culture.

Howard professor Charles Epps said, “I don’t know how Howard could have been more black. … [There’s no] black physics; there’s no black engineering; there’s no black medicine. The mission of the university was to train students to be competitive and competent whatever their field.

In the “Color Us Black!” documentary, Michael Harris, president of the freshman class, said the administrators were “content to shuffle, and they say ‘I shuffled; I bent. I kissed some feet. I made it. You do the same thing, boy, and you’ll make it.’”

Another protester said, “Our black administration seems to think that … they are showing the great white father how good we are. And the great white father is over there laughing at how stupid we are.”

But many of the students — though by no means all – saw the development of a black consciousness, as well as a connection with the surrounding black community in D.C., as part of Howard’s mission.

They also were among the first college students to see their campus as a microcosm, one where students, teachers and administrators should work to create the kind of world they wanted and not just prepare them for the world that was.

“Our perspective was that we should be about change, and not about replicating the status quo,” Israel said. “Because the status quo was not beneficial to us as a people.”

‘Black University’

On March 22, four days into the protest, some professors held impromptu classes on the quadrangle so that students wouldn’t miss critical work with the end of the school year approaching. A group of protesters hung a hand-made sign over the “Howard University” sign on the front of the building reading “Black University.”

Meetings between university officials and students continued, while official statements from the administration maintained a hard line. Nabrit, who was in Puerto Rico when the protest began, never returned for the talks. He was quoted, however, as saying “We have some good students, but we have some difficult ones … . I hope in dealing with them we can avoid something disastrous.”

The number of protesters numbered about 1,000 out of the roughly 9,000 students at Howard at the time, and not everyone was on the activists’ side: Student Bar Association asked the District Court to force the university to reopen. The judge said that if the law school wasn’t reopened by Monday, he would order the students to leave the administration building.

Israel at the time was quoted as saying that if the judge issued an injunction, “Many of us will stay here and be arrested.”

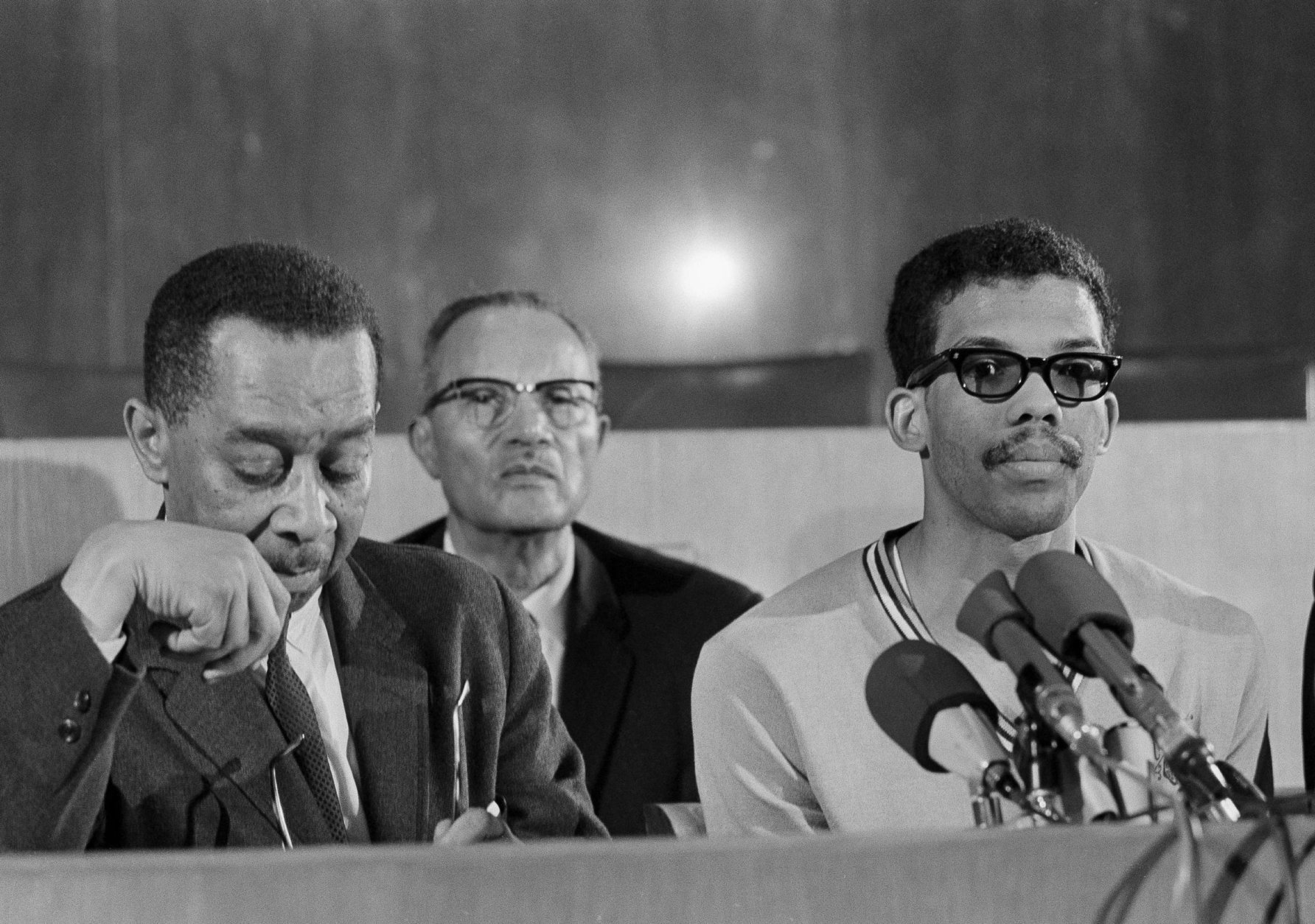

In the pre-dawn hours of Saturday, March 23, a deal was struck: Charges would be dropped against the 39 students involved in the Charter Day protests; the students got the student judiciary committee they wanted, and the next year, a seminar called “Toward a Black University” would be held at Howard to discuss curricula at the school, as well as other black colleges. Nabrit would not resign; he planned to retire at the end of the next school year anyway.

After an hour of discussion and a voice vote, the students agreed to the deal. It was announced that afternoon.

Israel didn’t say anything at the press conference announcing the agreement because “We agreed not to disagree in public. … I just wish we had asked for more.”

At the time, she mentioned seeing white people being beaten by the police at a protest march on the Pentagon. “If they’d do that to them,” she said, “I know they’d do that to us.”

She agrees now with Gittens and others that “I was wrong” to hold out for Nabrit’s resignation. A leader in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s and a counsel in the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that integrated American public schools, she realizes now that he’d earned the right to go out on his own terms.

But “there was a core of our demands that were not met,” she says now, specifically regarding the welfare of the black community. “And you can see now what I’m talking about, in [the area surrounding Howard] that’s being gentrified … the lower-income people around Howard are being forced out.” She thought Howard should take the lead in redeveloping the community in an affordable way, but “the administration said that wasn’t in their charter.”

Still, both agree that by and large, the takeover was the right thing to do. “It was what we were left with to get their attention,” Gittens said. “And it worked. … The university changed its direction. Things that are accepted now, that was not the case back about 50 years ago.”

‘They have to make their own decisions’

There have been more than a few protests and sit-ins at Howard since then, most notably a 1974 protest over a tuition increase, a 1989 protest demanding that notorious political operative Lee Atwater resign from the board after his racist comments became public, and another as recently as 2015. Gittens said he gets invitations to advise or be part of such actions, but stays away. “They have to make their own decisions,” he said.

“But I do know that there are people with concerns and issues, and who are trying to find a way to make sure the university remains on the proper course. … The need for the kind of education and training that Howard is offering is still a major need in our community.”

Israel says now that Howard is a better place than it was. She returned to earn a master’s degree in African studies from 1971 to 1973, and has visited a few times over the years. “I think Howard’s come a long way, and there’s a consciousness there that didn’t happen before,” she said, adding, “black people in general, we have a better attitude about ourselves than we used to have.”

Gittens said the protest taught him some of the most important lessons he learned in college: “You’re called to make decisions; you’re called to make assessments; you’re called to be a leader; you’re called to learn in order to keep it going, and survive in some instances. That’s the kind of experience that you can’t go to [just] any university to get.”

And he’s carried a few principles from his protest days with him throughout his life: “It’s hard to watch people mistreated … and sometimes you’ve got to put your body on the line. You’ve just gotta say ‘No. I will not let this continue.’ …

“And that’s a feeling that’s risky, and it can cost, but at the end of the day, you feel as though you’ve lived a life that has made some contribution along the way. And so you feel pretty good about your life. I know I do.”