The Carter G Woodson home is open for tours during February. He is known as the Father of Black History. This is the third floor of the home that's in the Shaw neighborhood. This is the third floor which is where he lived. The other floors were dedicated to his work. @WTOP pic.twitter.com/HWxPbWwMqo

— Kathy Stewart (@KStewartWTOP) February 11, 2018

National Park Service Ranger Danyelle Dukes giving a tour of the Carter G. Woodson home in Shaw. He is known as the Father of Black History. The home is open this month, Black History Month, for tours. @WTOP pic.twitter.com/BTHf9nuSCl

— Kathy Stewart (@KStewartWTOP) February 11, 2018

Nat'l historic site Carter G Woodson's home is open to the public during Black History Month for tours. The National Park Service spent years renovating the home which is now a museum. This is the site where he created Negro History Week which we know as Black History Month@WTOP pic.twitter.com/ooFvgt9UXh

— Kathy Stewart (@KStewartWTOP) February 11, 2018

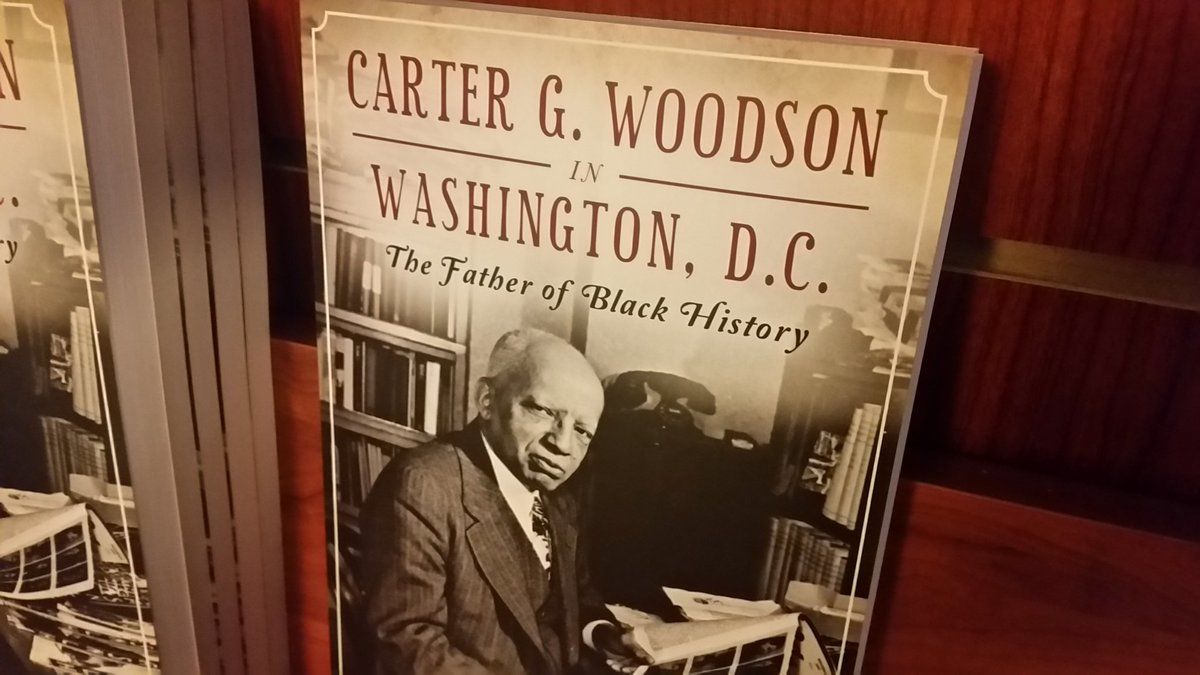

WASHINGTON — The home of the “Father of Black History” is already a national historic site in D.C.

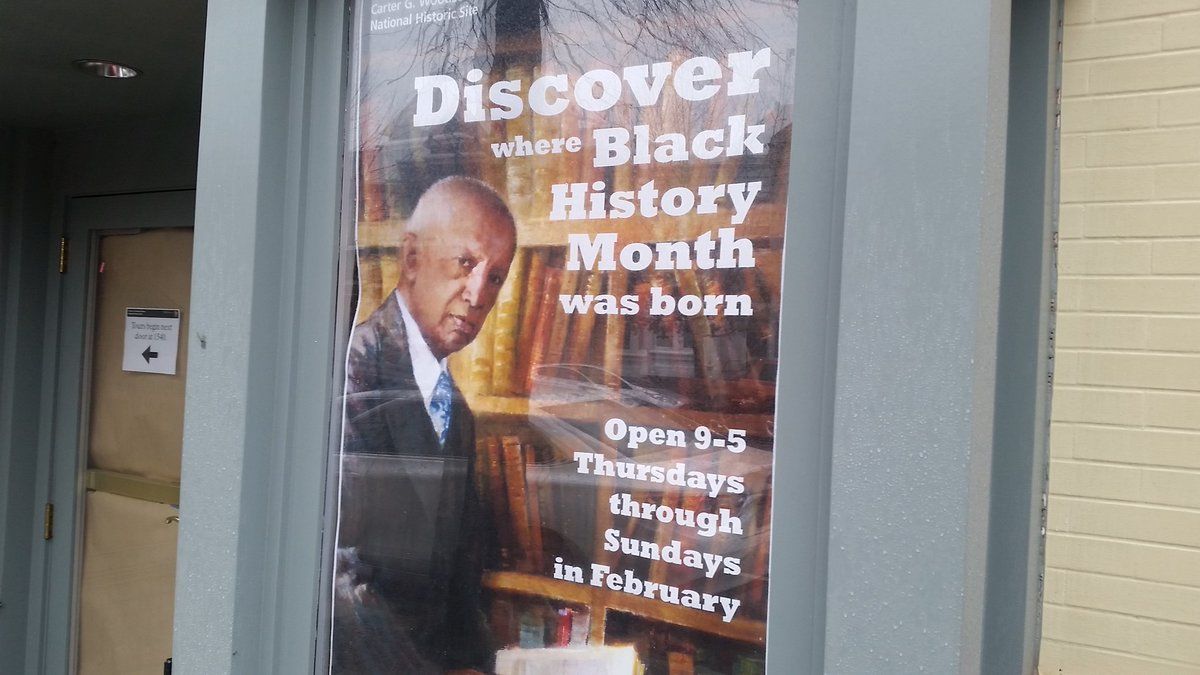

But for Black History Month, Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s home has been transformed into a museum where the public can get a glimpse of where a large part of African-American history was researched and preserved.

This is the first time the National Park Service has had Woodson’s home open to the general public as a museum during Black History Month after years of renovation, said Vince Vaise with the National Park Service. It’s open to the public Thursdays through Sundays from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The home is the site where Woodson created the idea for black history week, which was first coined as “Negro History Week” in 1926 by Woodson himself.

During a tour of Woodson’s home in Shaw, National Park Service ranger Danyelle Dukes told WTOP that Woodson acquired his Ph.D. from Harvard and then “he would go on to collect Frederick Douglass’ papers and donate them to the Library of Congress.”

The Shaw neighborhood is one of D.C.’s most historic African-American neighborhoods, Vaise said.

The home, located at 1538 9th St. NW, was Woodson’s office and also the site of his publishing company, “Associated Publishers.”

“It was one of the first publishing companies to publish historical works of African-American history,” Vaise said.

The house also was the headquarters for what’s now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Vaise said the building served as an “informal community center.”

The business operation sat on the first floor, and the second floor was the research area and where Woodson had his library and home office.

“The library has a number of the books he wrote but also a lot of the books he used in his research,” said Vaise. “There was also a safe up there because no one — really, no one — was even keeping archives. When he or his associates, his friends, researchers, came upon original documentary material, they acquired it and kept it in that little archive. Today, that’s at the Library of Congress.”

Woodson lived on the third floor, which Vaise said no one was allowed in, and lived there from 1922 to 1950 when he died of a heart attack in his bedroom.

Before Woodson, there was little accurate history written about the role of African-Americans and their contributions to the country.