WASHINGTON — You can tell when migratory birds are on the move: just look for the teams of volunteers armed with paper bags and small nets patrolling neighborhoods in D.C. starting from 5:30 a.m.

They are volunteers with Lights Out, a program connected to the urban wildlife rehabilitation center City Wildlife.

WTOP’s Kate Ryan met with Lisbeth Fuiz in the predawn hours near Union Station one recent Saturday morning.

“For two months in the spring and then two months in the fall, people go out seven days a week at 5:30 in the morning looking for live birds or birds that have died from collisions with windows,” Fuiz said.

Walking past the Thurgood Marshall Federal Judiciary Building, Fuiz pointed out the hazards the building poses to birds.

The building features a wide glass front that opens to an airy atrium filled with trees. It is inviting and looks serene. But the building is a textbook hazard for migratory birds.

“They’re attracted by the light, and they see the tree, and they want to get to the tree,” Fuiz said.

Unable to “read” glass as a solid, all the birds see is open space with a place to roost ahead.

Fuiz explained why the tiny travelers are so easily disoriented and fooled when they see what appears to be an open landscape.

“When they come into the city, they’re already exhausted and they’re looking for food and water — and they’re looking for a place to rest,” she said.

The goal of Lights Out is threefold. One aim is to save the injured birds; a second is to document as much information as they can on the birds that are found dead. A third goal is getting building managers to see the buildings the way the birds do and minimize the hazards various architectural styles can pose.

It sounds like grim volunteer work, and it requires committing to predawn hikes of 3 to 4 miles in the District of Columbia. Why do it?

“That’s a great question!” said Stephanie Dalkey, a volunteer.

Dalkey said she’s not a morning person. So what is the reward?

“It just becomes kind of an addiction,” she said. “Once you start finding birds, you want to be out there helping them if they’re alive or finding them if they’re dead — you don’t want to miss out on that data.”

Fuiz said that if the birds are found stunned but still alive, they are put into paper bags carried by volunteers. The bags provide a quiet dark space that can help lessen stress the bird is experiencing.

“Our protocol is that you wait until they’re fluttering in the bag, and you really know that they’re feeling lively,” Fuiz said. In that case, they can be released on the spot. If the birds seem to be in trouble, they are taken to City Wildlife for rehabilitation.

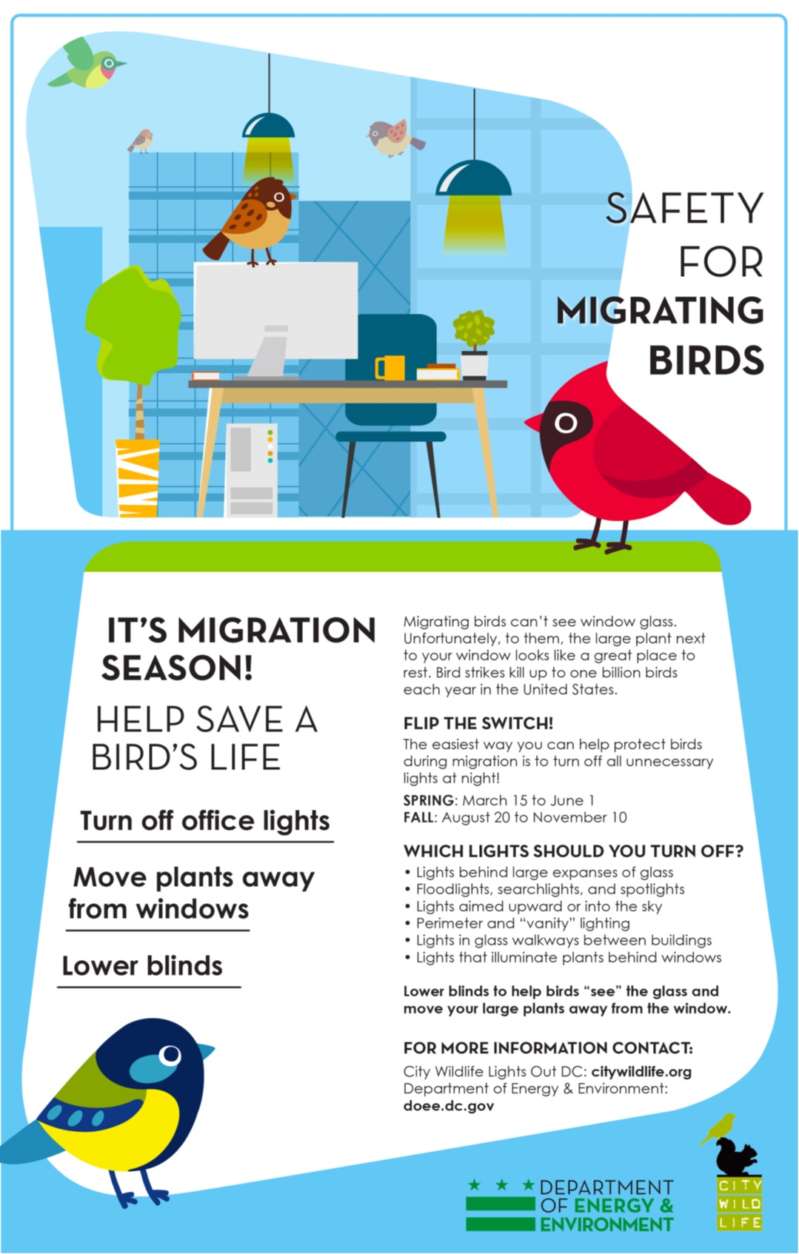

The wider goal of Lights Out is to get building managers and business centers to minimize the threats to migratory birds. Mary Lynn Wilhere, Program Analyst with the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment said the steps businesses can take are pretty simple.

“Turn off the lights at night, lower your blinds and move large plants away from the windows,” she said.

Once people understand the problems lights can pose, getting them to buy in to change is not too difficult.

“I think once we raise awareness on the issue, people are willing to do something about it,” Wilhere said.

“Most people love birds,” she said. “You don’t want to walk to your building and see that your building caused the death of a bird — especially when a simple step could have helped reduce it.”

Learn more about volunteering with Lights Out on City Wildlife’s website.