WASHINGTON — Recent Amtrak crashes and a push to operate more like a business demonstrate some key challenges for the rail service’s growth in the future, Amtrak’s inspector general’s office found.

Over the next two years, a report identifies key safety and security, governance and financial, customer service, procurement and maintenance, and I.T. and workforce risks that leaders have only just begun to address as Amtrak’s top management and performance challenges.

In the first ten months of the most recent budget year, 797 Amtrak passengers and 585 employees were injured. Three passengers and four employees were killed on the railroad.

Amtrak is due to submit a new safety management system plan to the federal government by Nov. 1 that includes plans to more closely watch for near misses like the approximately 115 major operating violations already recorded each year.

This year, the number of incidents of speeding, running a red signal or tampering with a safety device has declined. Amtrak has also promised to improve policies on drug and alcohol use and testing and to expand the use of confidential reporting systems so that employees can flag problems before a major incident.

For many of the changes to really make a significant difference though, the chief safety officer said during the review the improvements would need to be in place for about 5 years to address long-standing problems with the safety culture at Amtrak, a company that is now 47 years old.

Amtrak does not expect Positive Train Control, an automatic speed-limiting feature that can help prevent collisions, to be in place for all of its services by the end of the year. While it is in place along the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak expects 13 of 20 freight railroads it operates on elsewhere will not be fully ready to implement the safety system for Amtrak trains. Amtrak would consider each route separately in evaluating whether to continue operations on those lines.

Crashes that have killed or injured riders and workers at the same time many long-distance trains are consistently late at the ends of the lines have driven down ridership and raised concerns, particularly outside of the profitable Northeast Corridor.

For example, one train that runs through Washington, the Crescent between New York and New Orleans, has only been on time at the end of the line 13 percent of the time lately, largely due to having to stop and wait for freight trains to go ahead of it on freight-owned tracks south of Union Station.

State-supported routes, like Amtrak trains in Virginia, have seen on-time performance drop but are still on time more than 70 percent of the time.

Amtrak owns the tracks from D.C. to New York, which means it has more control over operations there.

For the long-haul routes, Amtrak has boosted sales offers and lowered prices in some cases to head off a ridership decline in the wake of the two deadly crashes in the last 12 months.

Elsewhere though, riders have noticed an end to some discounts for seniors or students and other ticket price changes meant to raise about $15 million by making train tickets work more like an airline. Amtrak is aiming to end operating losses by 2022.

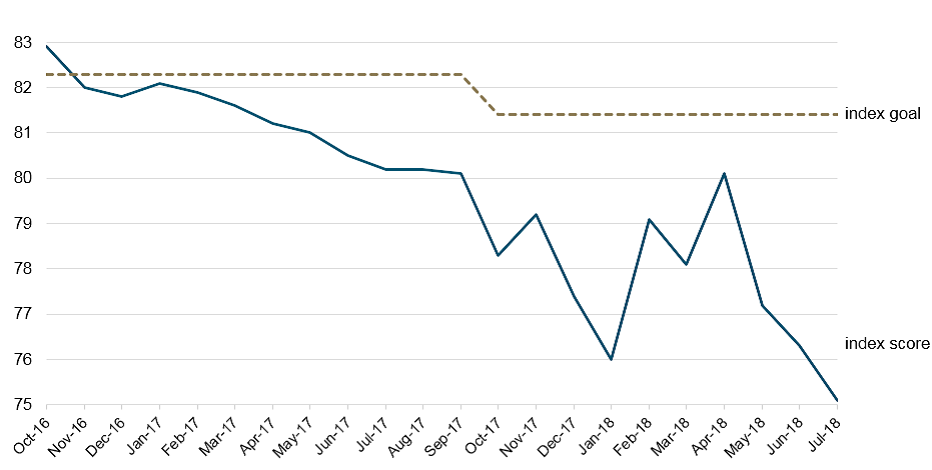

With a push to operate more like a business, Amtrak’s long-haul routes that provide service to areas across the country are the general drag on financial performance, and an effort to cut costs and push for higher ticket prices overall is not helping customer satisfaction rates. Satisfaction scores have consistently fallen for the last two years as Amtrak has significantly cut its adjusted operating losses to less than $200 million per year. Long-haul routes still lose around $500 million per year, which has prompted a complete reassessment of the nationwide routes.

“Adjusting the route structure in ways that would reduce operating losses could be difficult,” the inspector general said. “Making these changes will require balancing the company’s historical role of providing reliable intercity passenger rail service on a nationwide basis against the need to operate efficiently.”

Amtrak is trying to turn around the satisfaction rate decline with new customer service training for workers, more social media interaction, cleaner bathrooms on trains, and significant upgrades of trains and of stations like Union Station and Baltimore Penn Station, but the inspector general’s office finds there is anxiety about changes and concern about whether Amtrak has the right staff or enough well-trained people to handle all these massive projects all at once.

Amtrak does not appear to have enough engineering staff for safety work and track work on major projects, which creates risks of project delays.

Less than half of project managers had proper certifications to do their jobs, while in other cases, like the redevelopment of Baltimore Penn Station, Amtrak had not finalized a management and oversight structure to be sure the project went smoothly.

Amtrak is reviewing the size of its workforce and how many contractors it has.

There are about 16,800 union employees, 2,700 other workers and at least 3,100 contractors. Amtrak is conducting a review to identify the total number and type of contractors working for the company.

Major overhauls and long-delayed fixes along the Northeast Corridor alone require significant coordination and oversight, but Amtrak has cut staff to save money in the near term. About 19 percent of information technology department jobs are vacant after a reorganization meant to reduce duplication across Amtrak, which becomes an even more pressing concern in an era of regular cyberattacks on many organizations.

The needed upgrades also rely on funding from a variety of sources, including uncertain grants or loans from the federal government.

Just fixing the Northeast Corridor to a basic level of good repair is estimated to cost $38 billion.

Amtrak is also reconsidering how many locomotives and railcars it needs in the future as it plans purchases of new and upgraded versions.