Democratic Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, who has been fighting for years to change the way the military prosecutes sexual assault cases, is poised to finally remove those cases from the military’s chain of command after the Pentagon’s civilian leader endorsed the change last week.

But a major showdown is looming between lawmakers and military leaders over how the US armed forces overhaul their justice system to try to curb sexual assault within the military.

The lawmakers pushing for one of the most sweeping changes to the military’s judicial code in recent memory say they still are concerned that the military — and its allies in Congress — will try to water down changes they argue are necessary after Pentagon leaders have repeatedly failed to address the problem of sexual assault.

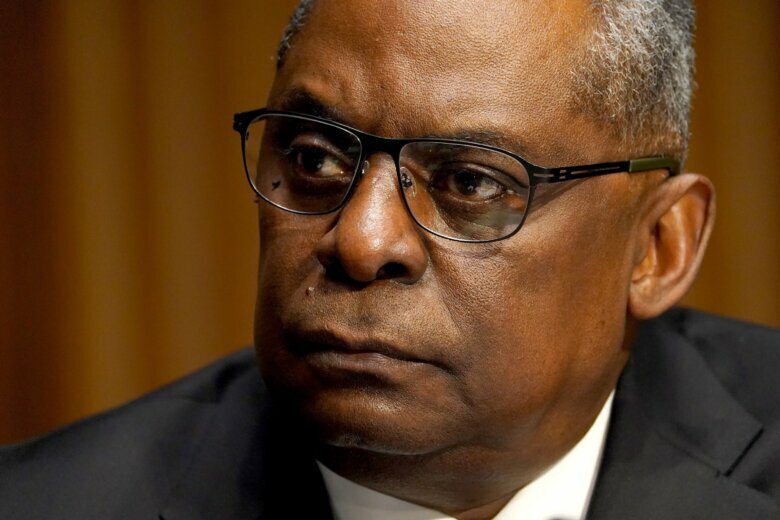

As Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin endorsed the removal of sexual assault and other related cases from the military’s chain of command last week, a key Senate opponent to changing the military’s judicial code released letters from all of the Joint Chiefs of Staff written in May that raised concerns about making broad changes to the military justice system.

At issue now is how the military handles other major crimes beyond sexual assault. While Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley expressed openness to changing the way sex crimes are prosecuted in the military, Gillibrand and GOP Sen. Joni Ernst of Iowa have written legislation that would move the decision to prosecute sexual assault, as well as most felony cases in the military, to independent prosecutors, away from military commanders.

Gillibrand argued that professional prosecutors, not commanders, should handle the prosecution decision for nearly all major felony cases, to address both the problem of sexual assault cases as well as a disparity in prosecutions affecting minority service members.

“I believe that the only reform that can address the two issues that are problematic — one, the prosecution of sexual assault in the military, and two, the racial disparities against black and brown service members — is to have a bright line at all felonies and take them out as chain of command against trained military prosecutors,” Gillibrand said.

But the Joint Chiefs raised concerns that taking the decisions over prosecuting most major crimes from commanders would harm their ability to maintain order and discipline in their ranks — a similar argument military leaders have previously made about sexual assault cases. Instead, they wrote that any change should be limited to sexual assault and other related crimes.

“Diverting nearly all serious offense to judge advocates could be counterproductive to our prevention efforts, which emphasize the critical responsibility of senior leaders,” Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael Gilday wrote in his letter.

The chiefs’ letters, which were written in May but released last week by Sen. Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, the top Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee, caught Gillibrand and Ernst by surprise. They underscored the tension between the lawmakers and military leaders as the changes are being debated by Congress.

Ernst told CNN it was a “problem” that she hadn’t been informed about the letters.

“I am disappointed in our military leadership. What they are trying to do is create what we see or what we call a ‘pink court,’ ” Ernst told CNN. “By separating certain crimes out, rather than all serious crimes, I think they have made a huge mistake.”

Despite the consternation about Gillibrand’s legislation, Austin’s endorsement of having independent prosecutors handle sexual assault causes is a significant victory for Gillibrand, who has repeatedly pushed for the change and has forced Senate votes on the matter since the Obama administration.

“I think it’s extremely powerful that we have a secretary of defense that is in favor of eliminating sexual assault and related crimes out of the chain of command,” Gillibrand said. “It shows he no longer believes convening authority is necessary for commanders to instill good order and discipline and for commanders to affect command climate.”

Gillibrand argued that also meant that command climate would not be affected if other crimes were also handled by independent prosecutors.

The New York Democrat is no stranger to Pentagon resistance to her efforts. She waged a battle against the Pentagon and the leaders of the Senate Armed Services Committee in 2014, pushing the Senate to hold a standalone vote on her bill that ultimately failed 55-45, short of the 60 votes needed.

But many of the senators who sided against Gillibrand seven years ago have watched as promises from Pentagon leaders to address sexual assault in the military have failed to lead to any tangible changes.

Now Gillibrand’s legislation has 65 co-sponsors, including Republicans Chuck Grassley of Iowa and Ted Cruz of Texas, giving her more than enough support in the Senate to pass it.

But a vote on her bill is a complicated proposition.

Gillibrand has gone to the Senate floor more than a dozen times since May to try to call up her bill for a vote. But she’s been blocked by Senate Armed Services Chairman Jack Reed, a Rhode Island Democrat.

Reed says the issue should be debated when the Armed Services Committee considers the annual National Defense Authorization Act, a sweeping military policy bill. Reed supports taking the decision to prosecute sexual assault cases outside the chain of command, but he has not endorsed Gillibrand’s broader legislation.

“You’re going to create a significant number of cases going to the special prosecutor, when my sense in the past has been they wanted to specialize in crimes related to sexual misconduct and have them limited to that number so they could be more effective and more efficient,” Reed told CNN.

Gillibrand and Ernst say the measure should be brought up separately, because the final defense authorization bill will be negotiated by committee leaders — where they can weaken provisions.

“They still have the ability to take it out against the will of the people on the committee,” Ernst said. “So do we trust them? No, we don’t, which is why Sen. Gillibrand has been so adamant about bringing it up on the floor.”

The House could ultimately prove to be a better avenue for Gillibrand’s legislation to get a standalone vote.

Rep. Jackie Speier, a California Democrat, and Mike Turner, an Ohio Republican, introduced the House version of Gillibrand’s bill last week. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi joined their news conference, saying she would bring the legislation to the floor for a vote.

One of the most importance voices in the debate may be House Armed Services Chairman Adam Smith, a Washington state Democrat who told CNN he planned to hold a markup on sexual assault legislation in his committee as soon as next month.

“Make no mistake about it, we are pulling sex crimes outside the chain of command, as it has been proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that they can’t handle it,” Smith said.

But Smith said he’s still genuinely undecided about whether he supports changing the way the military prosecutes most felonies, as Gillibrand has proposed, or keeping the focus on how sexual assault and other sex crimes are prosecuted.

“It’s kind of like the last person you talk to makes a really persuasive argument,” Smith said. “And Sen. Gillibrand makes a really persuasive argument. And I think DoD had a pretty persuasive argument as well.”