In the D.C. area, it is easy to find out how much the president makes, but do you know how much your co-worker takes home every payday?

Trying to figure out whether your salary is on par with your peers requires a delicate balance between transparency and privacy. For some workers, it’s hard to ask the question, “How much do you make?” and even harder to answer it.

“We’re not very good in our society about having conversations about money and personal finances. It’s something that’s taboo in many households,” said Mark Hamrick, Washington bureau chief for the financial services company Bankrate.

“America is a very individualistic culture,” said JR Keller, a professor of human resource studies at Cornell University. “People tend to focus on what they’re getting and what they’re making, and less (about) how that fits into a broader picture of everybody else.”

People don’t always want to talk about it, but they listen when other people do. Hannah Williams, 25, of Alexandria, Virginia, a data analyst for a government contractor, started asking people on the street last year how much they made and what they did for a living. She posted what she did on TikTok and soon launched the Salary Transparent Street series. Since last April, it has racked up more than 850,000 followers.

@salarytransparentstreet Georgetown, Washington D.C. 🌸 #salarytransparency #salarytransparentstreet #Georgetown #washingtondc #careertok #moneytok ♬ original sound — Salary Transparent Street

A step toward diversity

Salary transparency is a growing topic because it has a lot to do with fostering an equitable workplace — or an inequitable one. Diversity, equity and inclusion all have a stake in fairness in pay.

Williams told The Washington Post that the goal of her TikTok series was to “close the gender pay gap and remove discrimination opportunities that women and people of color face on a significant basis.”

Hamrick said, “The ultimate goal of transparency in pay is trying to strive toward fairness.” Without it, “the lifetime of employment that we’re familiar with have been more ripe for discrimination.”

“The last thing that one would want to see, while trying to promote those goals is to have a discrepancy in pay. That is the opposite of diversity, equity and inclusion,” Hamrick said.

Keller and his colleagues found that even when workers do share with each other how much they make, they may tend to ask those who are in the same demographic as them. Moreover, “We act much more strongly based on how we stack up against people who look like us,” Keller said.

He cites two main reasons for this. First, pay is a sensitive topic. And because it is sensitive, people are more likely to ask when they are friendly with each other. Keller said that research has shown that people are “more likely to have closer social relationships, both in and outside of the workplace, with demographically similar others.”

One of the implications of that is it becomes really difficult for workers to really uncover if there is pay inequality. “Because you don’t actually get a full picture of where you stack up against everybody else,” Keller said.

A generation gap

Keller said that for a really long time, organizations had policies that discouraged people from talking about pay at the workplace.

Recently, laws have been enacted in several states, including Maryland, Virginia and D.C., that prohibit an employer from taking retaliatory action against employees for discussing wages with each other. And effective Nov. 1, New York City employers join those in jurisdictions in California, Colorado and Washington state in including salary ranges in job postings under the New York City Pay Transparency Law, according to an update from the Society for Human Resource Management.

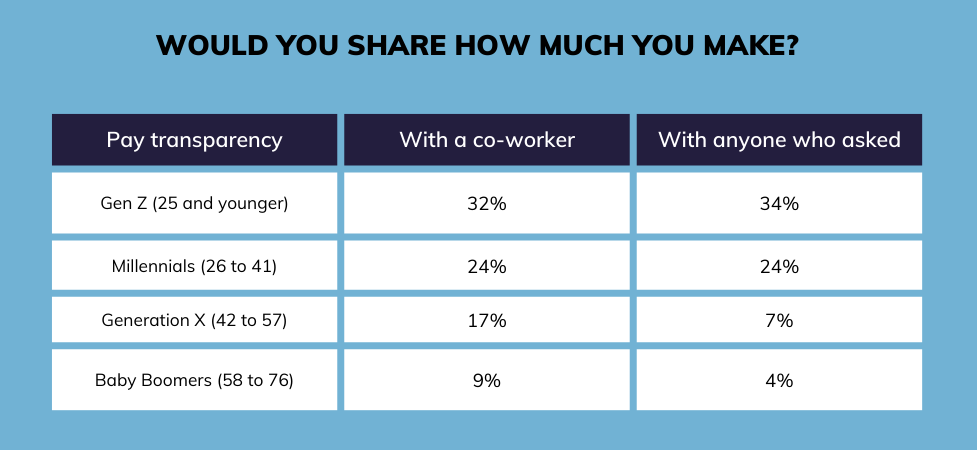

For younger workers, talking about how much they are being compensated is no big deal. A LinkedIn Workforce Confidence survey found that 81% of respondents 25 and younger (Gen Z) believe that sharing their pay information will lead to better equality in pay; 75% of those 26 to 41 years old (Millennials) agreed; 47% of 42- to 57-year-olds (Generation X) believe it would; and only 28% of those 58 to 76 years old (Baby Boomers) said transparency would lead to pay equality.

The survey of some 5,000 U.S. LinkedIn members conducted in June found comparable numbers across generations who say that it is OK to share how much they make with families. The bigger gaps are when it comes to telling a co-worker (Gen Z — 32%; Millennials — 24%; Gen X — 17%; Baby Boomers — 9%) and anyone who asks (Gen Z — 34%; Millennials — 24%; Gen X — 7%; Baby Boomers — 4%).

Older workers are less likely to share how much they are getting paid because there is a sense of “that’s how it’s been for generations,” Hamrick said.

He added that for older workers it is something they have never had to chat with their colleagues about and may not want to have that conversation. “It’s awkward,” Hamrick added.

The younger generation of workers, however, is not shying away from talking about it. Keller sees it in the students he teaches. “Everybody seems to know what everybody’s offer is, from every job or every internship. They openly talk about compensation and benefits,” he said.

Keller speculates that it’s because it’s a group that is much more attuned to issues around inequities and inequalities, which makes them more open to talking about these things.

Hamrick said younger workers have come of age at a time when there is ubiquitous access to information and disinformation; as they enter into a new job or new career, or as a more senior employee retires, they may be given comparable responsibilities, and they may wonder whether they are getting adequate compensation.

“There is essentially some motivation there for a younger worker to want to be given some assurance that they are being paid adequately,” Hamrick said.

How to have that ‘awkward’ conversation

Norms on how to talk about salaries are not common in the workplace, and there is a fair expectation that if you tell someone how much you make, then that would be reciprocated.

“I think people just worry that it’s not a polite conversation to have. And again, I think that gets back to sort of a cultural thing,” Keller said, adding that there is also concern about how you are going to feel if you learn that you are paid less than somebody else or the awkwardness when you realize that you’re making a lot more than your colleague.

Hamrick suggests taking a cautious approach when starting a conversation about personal finances with a colleague because it’s “delicate.”

And just because pay transparency is currently a big discussion, “There are tons of people in the workplace that value their privacy, and don’t want to have those discussions and shouldn’t be forced into doing so,” said Emily M. Dickens, the chief of staff and head of government affairs for the Society for Human Resource Management.

So how can you broach the topic?

“Something along the lines of, ‘I have a question about how much I’m being paid’ — or ‘how much we’re being paid. And I wonder how we can arrive at the answer.’ And if people take it from the perspective of a shared interest, rather than a personal or the worst-case scenario, selfish interest, that’s probably a better way to go,” Hamrick said.

How to bring up pay transparency to your company

Pay transparency is not just about revealing how much each employee is making; for companies, it’s also about helping employees understand how their salary is set, with the goal being building “employee confidence in the fairness of that process,” a study by professional services firm Mercer found.

Similar to Hamrick’s strategy for asking a colleague about pay, Keller said it is best to ask your human resources department or your manager about how much you are paid relative to your co-workers, as opposed to challenging how much you are getting paid.

When more people ask that question, “It puts the pressure on the organization to provide some information — maybe not about individual employees, but at least salary ranges and dispersion within different areas of the organization,” Keller said.

Dickens said it is on the managers and the organization to make sure they are monitoring their compensation numbers. Organizations should spend time educating staff about the compensation package, she said, and employees should make sure that they are comparing themselves not to their peers within the organization but the market for their industry.

As more people bring up pay transparency with their organizations, it can also be useful in identifying inequalities that may be unintentional.

“You may have a bunch of people who are equally qualified, but one person was hired … when the market went crazy, and so they’re making 20% more than all their other colleagues doing similar work. If their colleagues recognize that and realize that, it’s going to cause retention issues going forward,” Keller said.

Dickens said that 58% of U.S. organizations already voluntarily conduct pay equity reviews to identify possible pay differences between employees. SHRM recommends that companies do these audits at least annually, or every time there is a change to the organizational chart.

And a pay equity review is good for retention. “You don’t want anyone to think that they’re being unfairly treated. … You’re doing it to make sure that you can keep your talent that you have within your organization and that they feel rewarded for the work that they do,” Dickens said.