WASHINGTON — Whipping up a sumptuous dish in the kitchen has a lot in common with building a savvy financial portfolio. The skills and approach you would use to cook up, say, a delicious and nourishing soup are very similar to the way you should be thinking about establishing the foundation for your long-term financial future.

Please join me in my “kitchen” to find out more about how preparing something as simple as soup can teach you plenty about how you can cook up your future financial success.

Step 1: Decide what you want to make

Before you even begin cooking, you need to first answer a few questions: Do you have a good recipe you want to follow? Will your soup be the start of a special meal, or a hearty meal all by itself? How long will it take to prepare? Do you or your loved ones have any dietary restrictions? By answering questions such as these, you’re more able to identify the kinds of ingredients you’ll build your meal around.

You can use very similar questions when starting to map out your investment plan:

- What are your investment goals?

- What is your time horizon?

- What is your risk tolerance?

- How much money will you start with?

- Will you continue to add money on a regular basis, and will you need to take any withdrawals from your portfolio?

- Are you committed to maximizing your investment plan through all market cycles?

The answers will go a long way in helping to shape the recipe for the financial plan that will work best for you.

Step 2: Follow your recipe

Once you know what ingredients you’ll need for your meal, it’s time to consult the recipe to determine how much of each you’ll need to use. A good chef carefully measures and mixes all the ingredients together to create a flavorful soup, so that no single ingredient will overpower the others. The best flavors come from balancing and blending.

A good investor carefully combines multiple asset classes to create a well-diversified portfolio that generates consistent long-term returns along with reduced risk. Each asset class has its own risk/return profile and behaves differently over time, based on a series of variables such as the economy, interest rates, inflation, specific industries and the markets. When you find the right balance of assets, the end result can be a more consistent return with fewer bumps and volatility.

If we were to think about our financial plan as a recipe for, say, roasted carrot ginger soup, our list of ingredients might look like the following:

- Stocks = vegetables: 60 percent

- Bonds = chicken broth: 15 percent

- Multi-strategy funds = ginger: 15 percent

- Real assets = brown sugar: 5 percent

- Cash = butter: 5 percent

Your stocks (your vegetables) form the core of your long-term growth assets, which is why they represent 60 percent of your recipe. Just like you need to pick fresh vegetables for your soup, you need to have a solid collection of stocks or stock funds in your portfolio.

Investing in stocks is essentially buying ownership in a company. Some companies pay regular dividends from earnings (characteristic of a “value” stock), while others reinvest their profits and pay no dividends (which we typically call “growth” stocks). Your goal should be to have a mix of both, as well as businesses that are based around the world and that invest in multiple industries. A well-diversified stock portfolio also consists of different-sized companies including a range of large, mid- and small capitalization.

In terms of the stocks, or vegetables, in our recipe, we might have a shopping list that looks something like:

- Carrots = U.S. large, mid- and small capitalization stocks: 25 percent

- Parsnips = International and emerging markets stocks: 25 percent

- Onions = Global/U.S. hedged equity stocks: 10 percent

But to make a delicious soup — and a diversified portfolio — we need more than just vegetables.

Next, we need to add some broth — or bonds — to our pot. Bonds are steadier and less risky than stocks, which brings that smooth consistency we look for in both a soup and a portfolio.

But we also don’t want things to be too bland, so our recipe calls for a dose of ginger — or a “multi-strategy” asset class, which invests in various strategies that have a lower correlation to both stocks and bonds. The goal with these assets is to achieve annualized returns of about 5 percent to 8 percent, with a bit higher risk than bonds.

Our recipe also calls for some brown sugar, which we call “real assets” — investments in real estate, commodities, master limited partnerships and other assets that tend to share characteristics of both stocks (earnings growth) and bonds (yield).

As a final touch, adding a little butter or cash, allows you to take advantage of unique opportunities.

Now, grab a glass of wine

Let’s pause for a moment to talk about the value of diversification when it comes to selecting the ingredients in our recipe. It might be tempting to load up on U.S. stocks, for example, since they have outperformed foreign stocks on an annual basis since 2010. But it’s critical to note that all asset classes have cycles. The U.S. does not have a monopoly on stock market returns, profit growth, dividend payments, innovation or good ideas.

At some point, cycles turn, and underperforming assets suddenly begin to outperform last year’s stars. No one can predict when cycles change.

Consider the following chart, which shows annualized performance and volatility over the past 15 years — from Dec. 31, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016, as reported in JP Morgan’s Guide to Markets published Dec. 31, 2016:

Asset Class Return* Volatility*

“Asset Allocation” Portfolio** 6.9% 11.0%

S & P 500 Index (US Stocks) 6.7% 15.9%

MSCI EAFE (International Stocks) 5.8% 19.2%

MSCI EM (Emerging Market Stocks) 9.8% 23.8%

Barclays Aggregate (Bonds) 4.6% 3.5%

*Annualized Return and Volatility (Risk) for the last 15 years from 12/31/01 to 12/31/16. You cannot invest in an Index. Index returns include the reinvestment of all dividends and interest, but do not include fees, trading costs, or expenses which would lower any actual returns.

**Asset Allocation Portfolio assumes a portfolio constructed with investments in the following weights per Index: 25% (S & P 500), 10% (Russell 2000), 15% (MSCI EAFE), 5% (MSCI EM), 25% (Barclays Aggregate), 5% (Barclays 1-3m Treasury), 5% (Barclays Global High Yield), 5% (Bloomberg Commodity) and 5% (NAREIT Equity REIT).

(Graph courtesy Bridgewater Wealth & Financial Management)

Step 3: Use different cooking techniques

Not only can a diversified mix of ingredients make a better recipe, but a good cook can also use a variety of techniques, such as roasting, blending and boiling, to develop layers of flavors. Similarly, your investment portfolio can use different investment vehicles such as individual securities, mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) to generate desired returns. There are plenty of good mutual funds and ETF options, for example, that are passively managed to mirror specific benchmarks, like a market index. Actively-managed funds and ETFs are designed around specific investment objectives. Both vehicles can enhance your financial recipe as they offer professional management, diversification, liquidity, and low transaction costs.

Morningstar.com, Investopedia Mutual Funds Basics Tutorial and Investopedia Exchange Traded Funds are a few resources to help you become more familiar with these investing options.

Step 4: Add spices — judiciously

How much to spice up your recipe is a personal preference — but don’t let your emotions get the best of you. Think of over-spicing as greed and under-spicing as fear.

Some investors think they can outsmart the market by timing their investments. But investing too heavily in one stock or sector can add a lot more risk than you intend, which is why it’s critical to be mindful of over-concentrating your portfolio in risky assets.

Fearing every market downturn, on the other hand, is not only emotionally draining; it could result in missing the best days of the market and deter you from reaching your long-term investment goals.

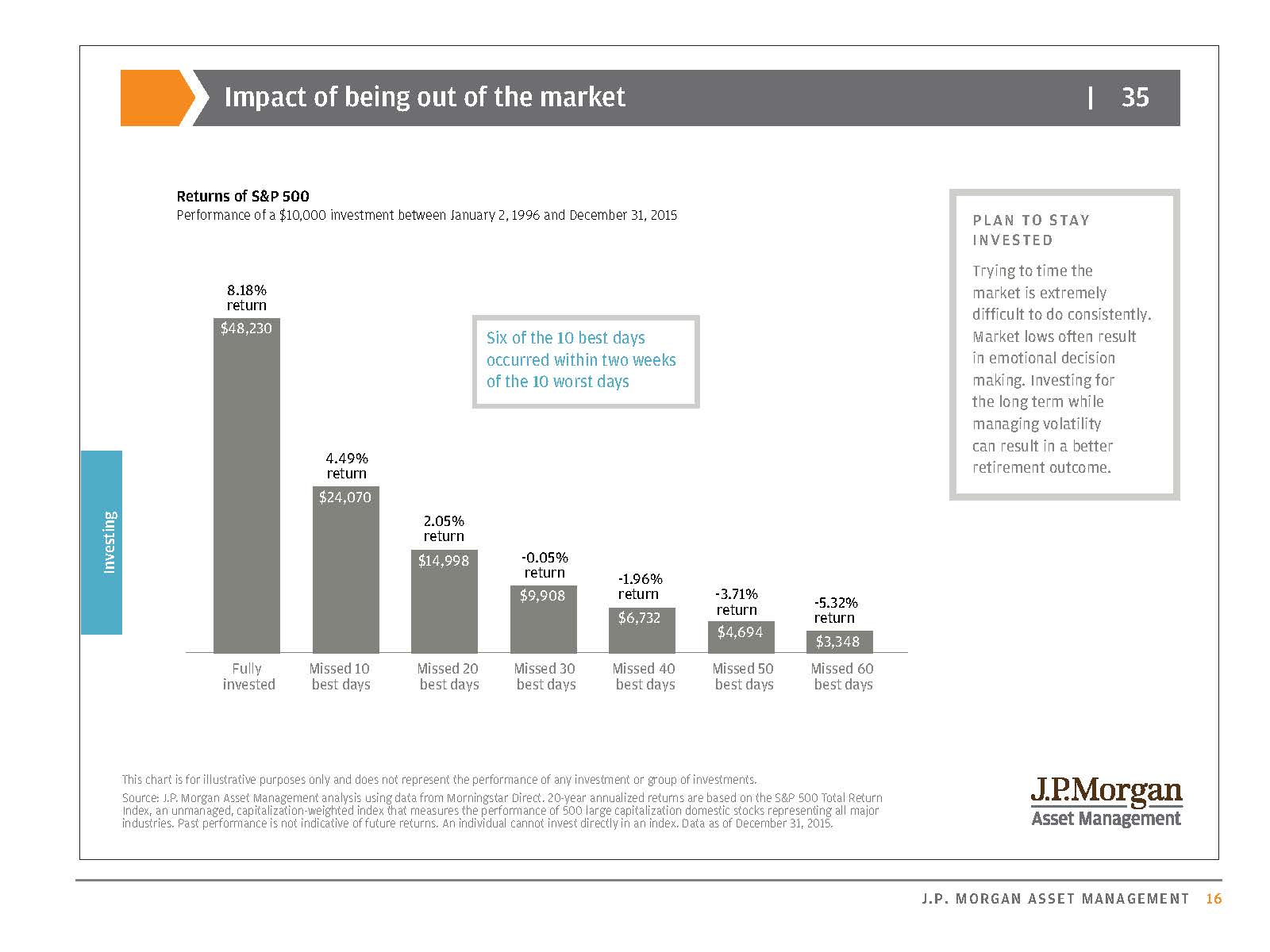

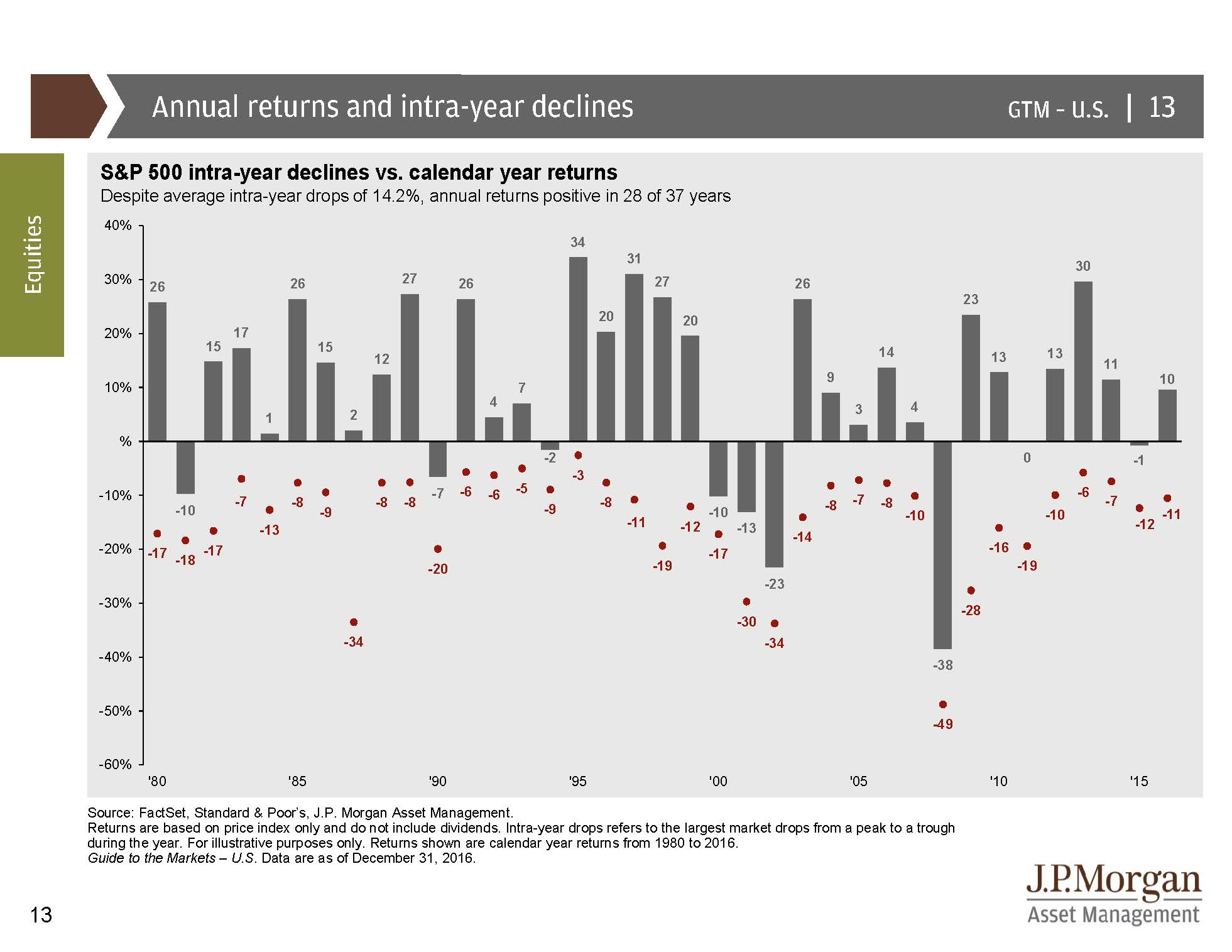

The attached two charts illustrate why it’s smart to remain invested for the long-term at all times, and accept volatility as a normal part of investing.

The first chart shows what happens if you try to time the market and miss the best days. An investor who stayed fully invested in the S & P 500 from 1996 through 2015 had an average return of 8.2 percent. Had you tried to time the market and missed the 10 best days over that time, your average annualized return for the same 20 years would have been 4.5 percent. If you missed the 20 best days, your return would have been just 2 percent.

The second chart shows that during the 37-year period from 1980 thru 2016, the S & P 500 had positive annual returns in 28 of those 37 years (~ 75%) and 9 years of negative or zero returns (~25%).

However — and this is important — the average of all intra-year drops from top to bottom during each of these 37 years was 14.2 percent. In other words, volatility is a normal part of investing, so don’t let it derail you. Investors need to stay invested and not overreact, so spice carefully.

Step 5: Skim off the fat

Everyone tries to eat healthy, and sometimes that means ladling off any fat that bubbles to the top of your soup.

In the investment world, that would mean being mindful of lower fees and tax efficiency. You should invest in funds that have no upfront commissions or loads. You should also look at your fund’s expense ratio relative to its peers for the lowest expenses. A passively managed index fund or ETF will charge a lower fee than an actively managed fund. Compare net-after-fee returns between different funds to justify paying higher fees.

Investors and market-timers who trade often generally experience higher transaction costs compared to a buy-and-hold strategy.

In terms of tax efficiency, capital gains realized from investments held for longer than 12 months will be taxed at the more favorable long-term capital gains rate than if held for under 12 months. It pays to be mindful of short-term vs. long-term timelines.

Step 6: Taste your soup often

Just like a soup needs to be stirred occasionally and tasted for flavor, your investment portfolio needs to be checked and rebalanced regularly. Do not leave your portfolio on autopilot. Make a point of reviewing your quarterly performance reports, and rebalance your portfolio when the asset classes in your recipe start getting out of alignment by more than 10 percent from your intended weightings.

Step 7: Simmer for best results

The final ingredient to a tasty soup is patience; the longer you let it cook, the tastier it becomes as the flavors continue to develop.

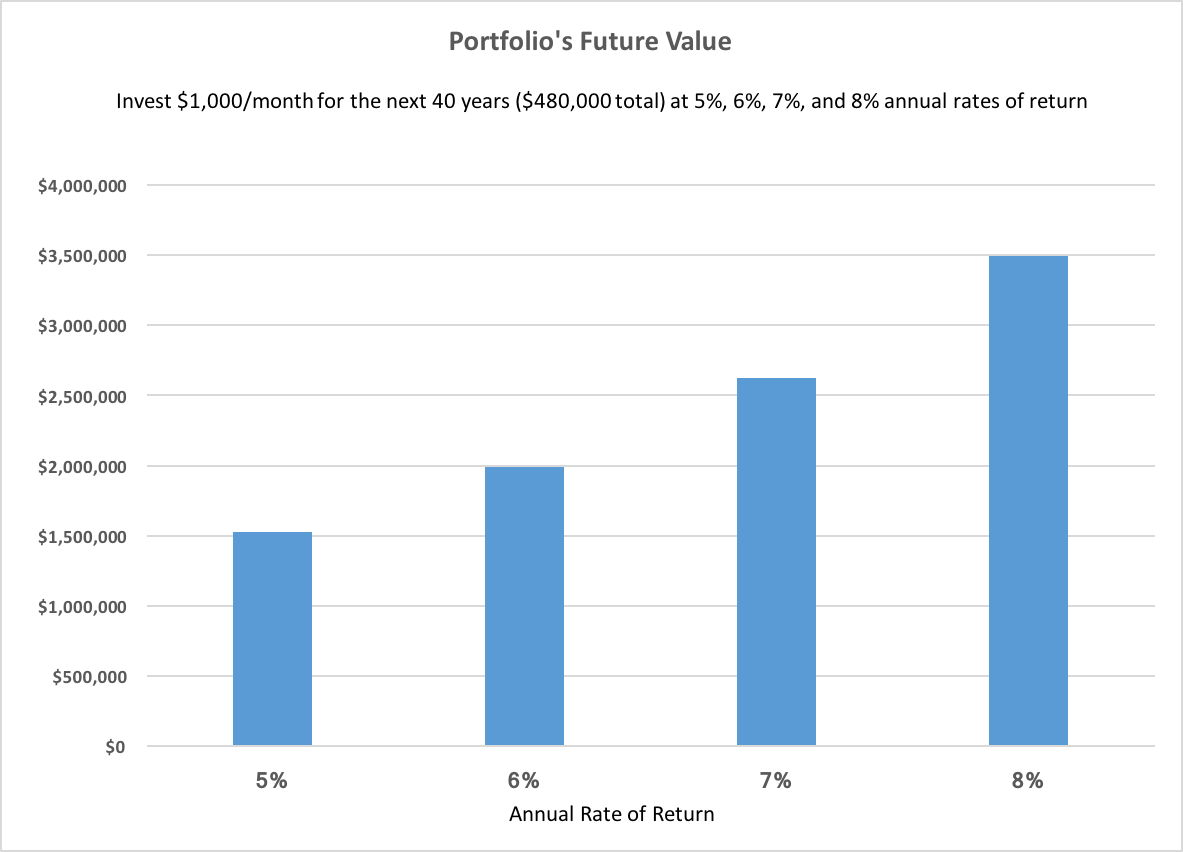

Investing also takes patience. Money grows on money by compounding each year. If you only invest $1,000 a month for the next 40 years (a total of $480,000), your portfolio’s future value would look like this:

(Graph courtesy Bridgewater Wealth & Financial Management)

The point is that investors, like chefs, should start with a great recipe and solid technique and let the flavors develop to their full potential over time.

Oh, and try my favorite recipe for roasted carrot ginger soup. It really is delicious!

Nina Mitchell is a senior wealth adviser and partner at Bridgewater Wealth & Financial Management, and co-founder of Her Wealth.

Not a specific guide to investing, and not a recommendation or advice to purchase or sell any security, investment, or portfolio allocation. Consult a financial adviser about your personal investment goals, objectives, and risk tolerance for as asset allocation recommendation.

Additionally, please be aware that these returns are hypothetical and past performance is not a guide to the future performance of any manager or strategy, and that the performance results displayed herein may have been adversely or favorably impacted by events and economic conditions that will not prevail in the future.

These future value calculations assume a rate of return not typical year after year, are gross of any fees and expenses, and do not account for whether the return came from dividends or growth. An actual portfolio’s performance returns would be impacted by dividend reinvestment and diminished as a result of actual fees and expenses.