This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

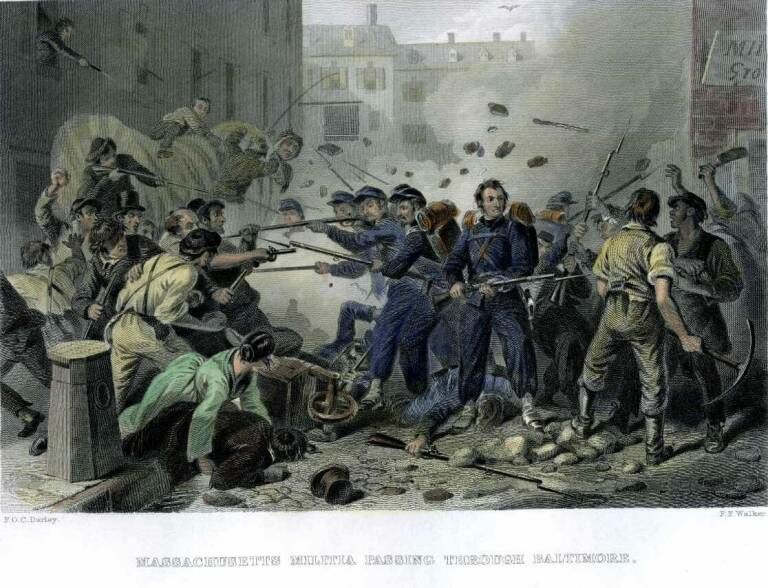

An angry mob gathered in the streets, many armed with makeshift weapons, intent on inflicting harm on those in uniform.

This deadly confrontation occurred 160 years ago, on April 19, 1861, in downtown Baltimore.

On the eve of the Civil War, Union troops from Massachusetts were passing through the city by rail on their way to Washington, D.C., to defend the capital. But before they could leave town, the soldiers were taunted and pelted with rocks and bottles by Southern sympathizers on Pratt Street. Shots also rang out, and during the hours-long melee, 12 Baltimore citizens and four soldiers from the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment were killed. They were believed to be the first casualties of the Civil War.

That somber anniversary is prompting local historians to reflect on what some call disturbing similarities between that deadly confrontation and the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

“The passion was about the same,” says Robert I. Cottom Jr., author of “Maryland in the Civil War: A House Divided.” “I think the sight of Union troops marching through Baltimore just enraged a lot of people much like Jan. 6 in Washington. But Jan. 6 was started by the mob. It wasn’t started by the troops or by their presence. The Capitol Police were just standing there where they were supposed to be. The invasion came from outside.”

Cottom, who was also the longtime editor of Maryland Historical Magazine, adds “If you look at the television shots [on Jan. 6] and put some of that in a crowded city street [Baltimore] and you get a good picture of what the 1861 riot was like.”

Just one month earlier, credible threats of a plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln forced the future president to travel in disguise on a train passing through Baltimore on the way to Washington before his inauguration.

Historical accounts of the time say a Confederate flag was posted outside the headquarters of Southern sympathizers in downtown Baltimore. A well-publicized photo from Jan. 6 of this year shows an insurgent carrying a huge Confederate flag through the halls of the U.S. Capitol.

Although Marylanders were deeply divided over the Civil War, the General Assembly rejected a bill that spring which would have authorized the state to secede from the Union.

Jamie Stiehm, a Washington political columnist and historian, was covering the Electoral College certification vote on Jan. 6 to certify Joe Biden as president when the Capitol was stormed by supporters of President Trump. Stiehm says she heard the gunfire as other journalists, members of Congress and staffers were evacuated to secure areas of the Capitol complex during the violent uprising.

As for the 1861 riot in Baltimore, Stiehm says “The mob was full of Southern sympathizers in a slave state. They were not enlisted in the Confederate army. We’d call them white male supremacists today, a civilian mob organized against the authority and power of the American government. They are very much a historical forerunner of the mob which stormed the Capitol.”

Former Maryland Secretary of State John T. Willis, author of the book “Maryland Politics and Government,” says “I wouldn’t conflate the two events, but I can see that some of the attitudes of those involved are similar with both incidents.”

Willis, executive in residence with the University of Baltimore School of Public and International Affairs, adds, “In the 160-year difference, we still see strands of political and social tension that have existed in our democracy.

“What erupted in Baltimore that day, that anti-federal government sentiment about unlawful exercise of power and fervent disagreement with the course of where government should be going was linked in a variety of ways to what exhibited itself on Jan. 6 in the speeches and invasion and insurrection at the Capitol.”

The Baltimore riot inspired James Ryder Randall, who knew one of the Southern sympathizers killed by Union troops, to write lyrics to the song “Maryland my Maryland.” The song, which described Lincoln as a tyrant, was often sung by Confederate troops during the war. However, it was not adopted as the official state song until 1939.

“That was the height of the anti-Black era,” Cottum says. “Lynchings were enormous in the 1920’s and 30’s. Among whites, there was a huge wave of Confederate nostalgia. It was the height of Jim Crow.”

Cottom says that’s when many Confederate monuments were erected around the country.

After decades of debate, the General Assembly recently voted to abolish “Maryland, My Maryland” as the state song. Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) has not yet announced whether he will sign the bill into law.

“I always wondered why it took so long to abolish the state song,” says Willis, since he says the lyrics clearly reflected an anti-Lincoln and anti-Union sentiment. Willis adds it is fitting that Maryland legislators have finally taken action to retire the controversial song on the 160th anniversary of its inception.

John Rydell has covered state politics for more than 30 years with WBFF-TV and Maryland Public Television. He can be reached at jprydell@verizon.net.