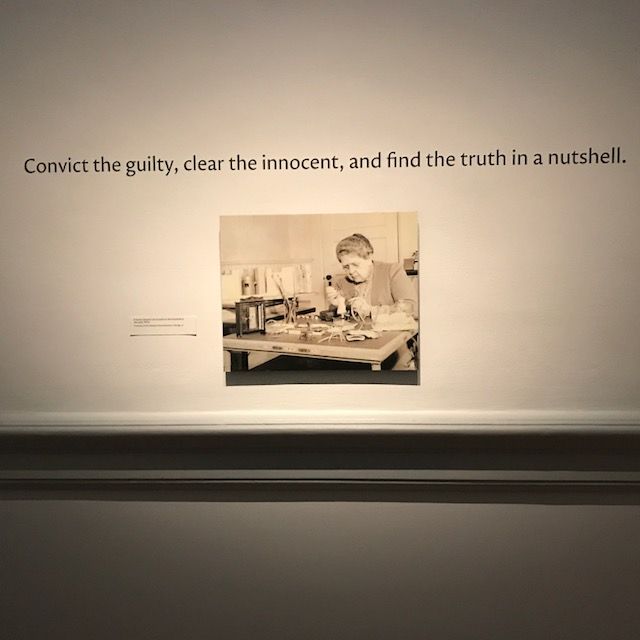

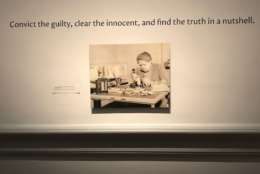

WASHINGTON — Frances Glessner Lee was a woman in the male-dominated field of forensic science, but she turned to the traditionally-feminine hobby of crafts to help “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”

Lee’s work is the focus of the temporary “Murder is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” exhibit at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Lee, who died in 1962, reformed the field of forensic science through dollhouse-sized dioramas of real crime scenes she designed. These glass-enclosed dioramas now fill two dim-lit rooms in the Renwick.

The temporary exhibit opened in October 2017 and will run until Jan. 28, 2018.

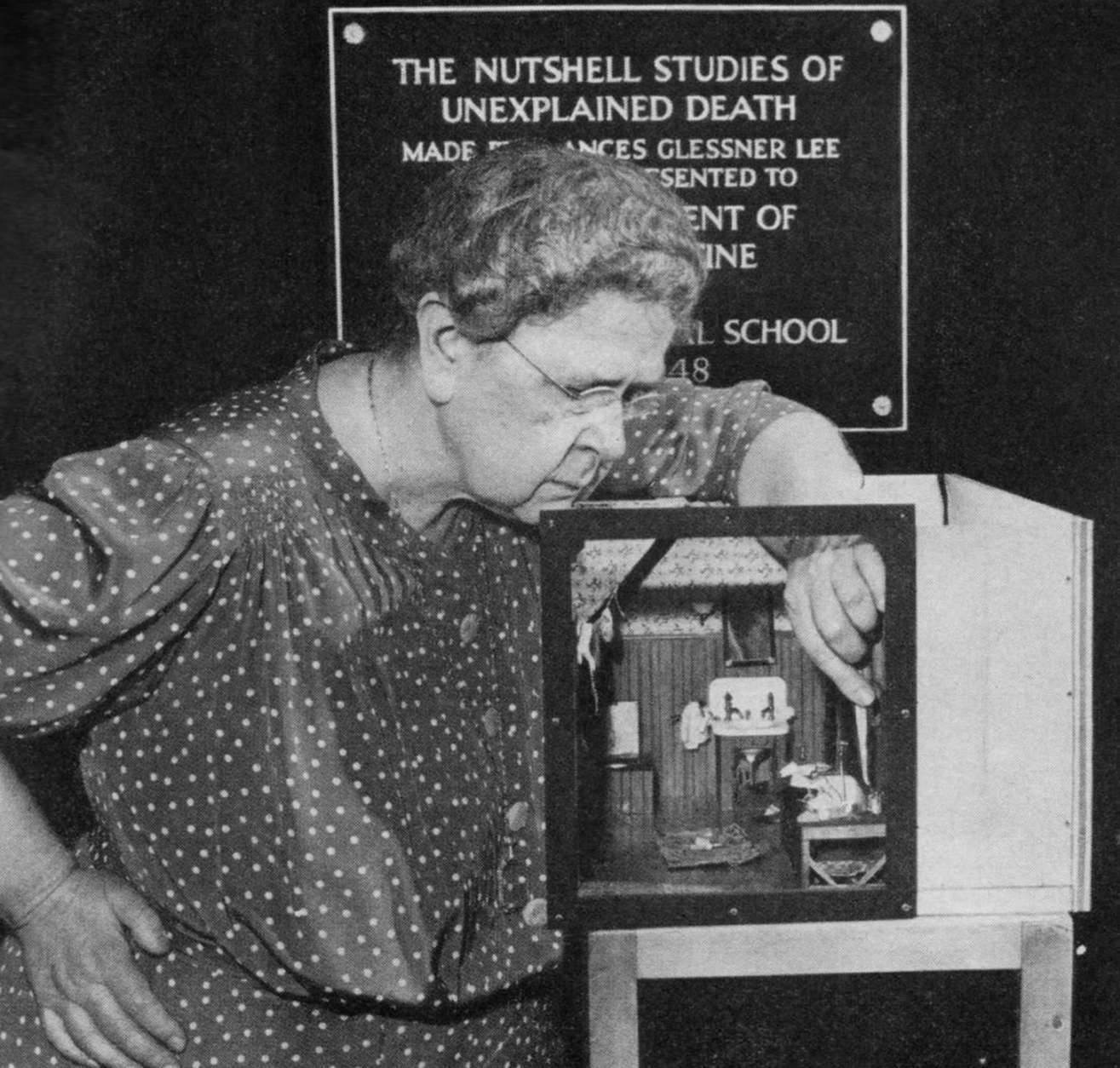

The dioramas, called “Nutshells,” were used to train homicide investigators in the 40s and 50s. Handcrafted and incredibly detailed, Lee recreated (and sometimes embellished) real crime scenes as not to give away to her students the answers of what happened, but rather to invoke deductive reasoning: Was it a homicide? A suicide? Death by natural causes?

Every diorama features a corpse — or two, or three — and is titled and explained in a nearby label. These “reports,” written by Lee, never name the lead suspect and thereby induce the same kind of thought expected of Lee’s students from the gallery’s visitors.

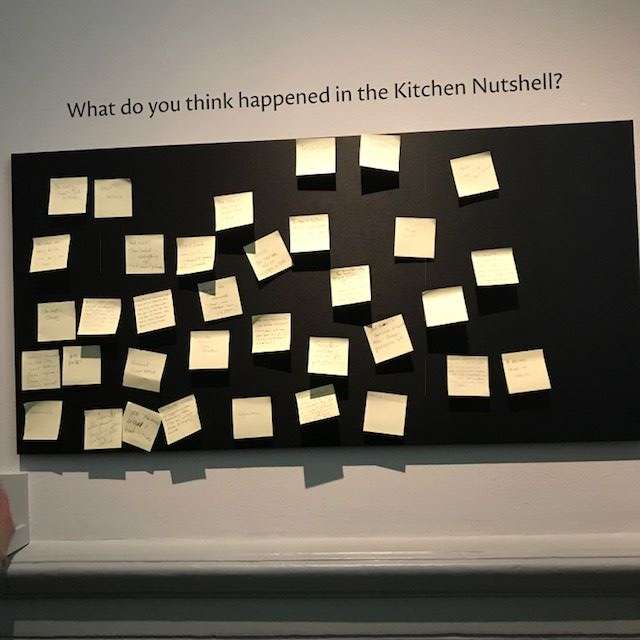

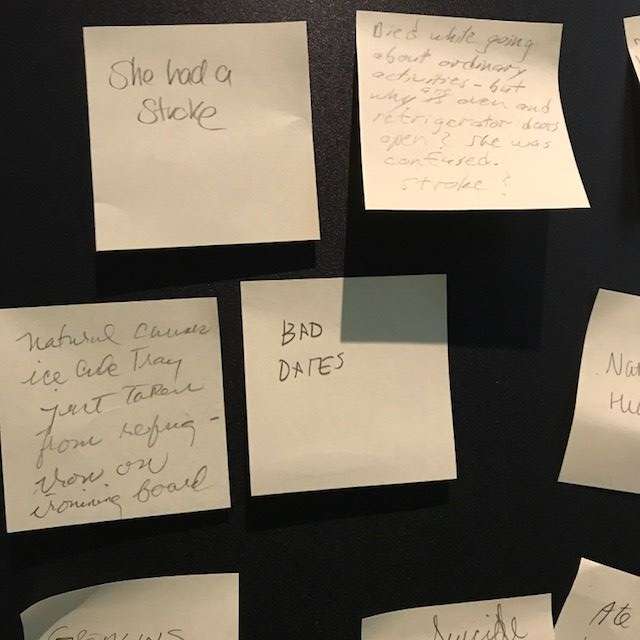

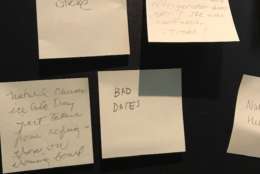

Visitors are encouraged to investigate the Nutshells rather than numbly look on — and investigate they do. On one wall, a board of Post-it notes hangs below the question: “What do you think happened in Kitchen Nutshell?”

“Kitchen Nutshell” refers to the diorama titled “Kitchen.” In it, a female doll representing a victim lies on a kitchen floor. The label says her husband had returned from an hourlong outing to find all the doors and windows locked and the house smelling heavily of gas fumes. He called police after breaking into his own home. “Kitchen” showcases the scene as investigators found it.

So what happened in “Kitchen Nutshell?” Since the label doesn’t explicitly say, the nearby Post-its from visitors claim the woman in the diorama may have committed suicide or even “ate too much bread and had a stroke.”

The immersive exhibit takes up two rooms where visitors are welcome to whisper their theories to one another. Under the dim lights, the meticulous details of Lee’s work are hard to see, but thankfully every “Nutshell” has a flashlight — the tool that transforms the visitor from museum-attendee to student of forensic science.

And in between the different dollhouses are facts and pictures of the “godmother of forensic science,” Lee.

Multiple labels tell her story: She was the first female police captain in the U.S. She helped to found the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University when the field of forensics was still new and crime scenes were often mishandled or poorly investigated.

In one label discussing how the dollhouse was originally meant to “teach upper-class young ladies the skills of managing a household,” it states that Lee, who was a wealthy divorcee, never took to the role of the domestic housewife.

Another label shares that Lee “would have never considered herself an artist,” but she still creatively added to the crime scenes she recreated by adding details from her own life into the dioramas in a way that shared “moralistic lessons, symbols, and occasionally bits of humor.”

No matter what Lee thought of her dioramas, they remain as useful as they are pleasing to the curious eye. They are so effective, they are still used in training seminars today at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore, according to the Renwick.

And for the first time since 1966, the 18 pieces on loan to the Renwick from the Harvard Medical School via the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner will be reunited with another diorama from the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, courtesy of the Bethlehem Heritage Society.

The exhibit was organized by curator Nora Atkinson.

For more information about location and hours the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Art Museum, click here to visit the website.