Throughout February, WTOP is celebrating Black History Month. Join us on air and online as we bring you the stories, people and places that make up our diverse community.

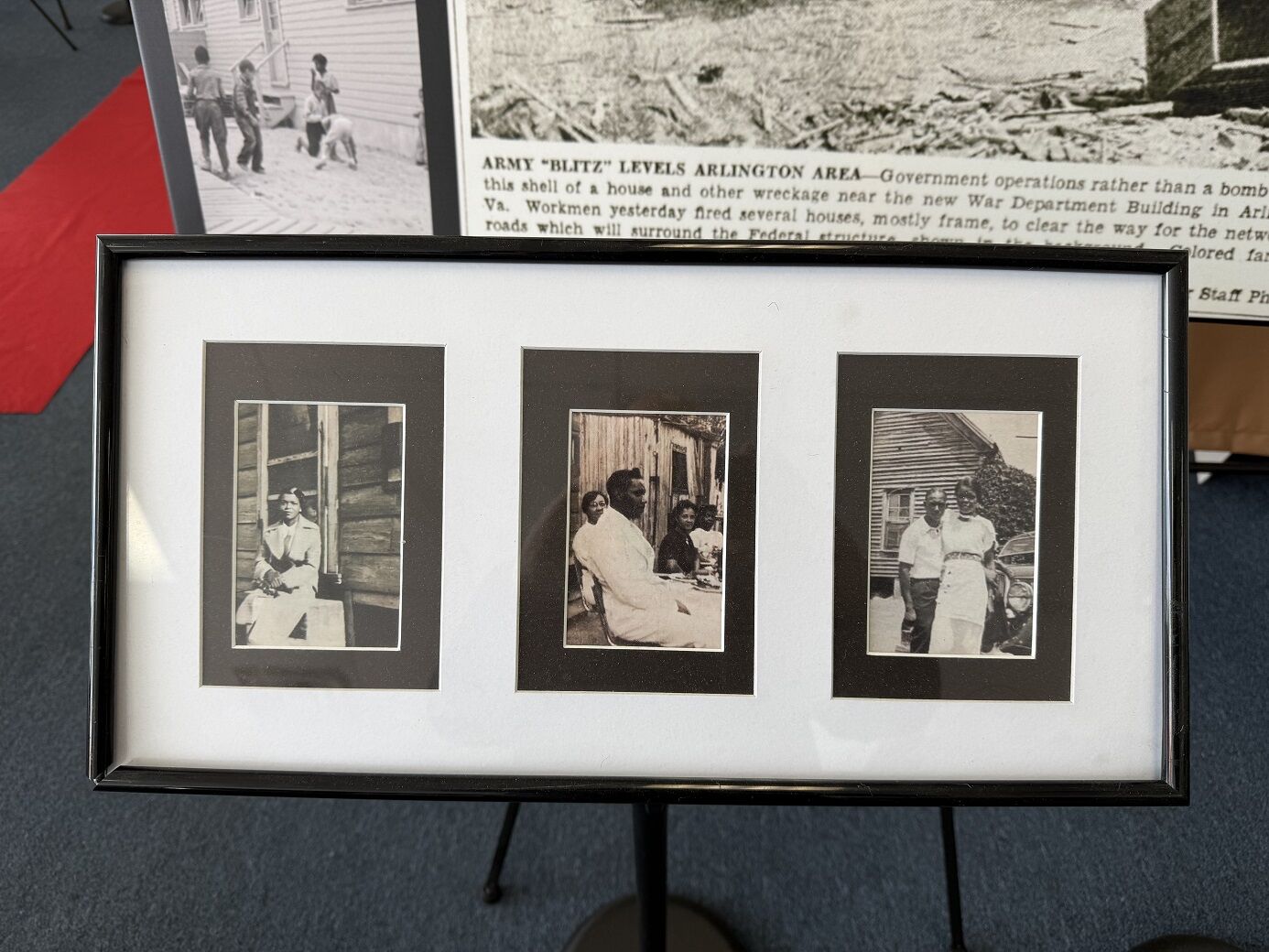

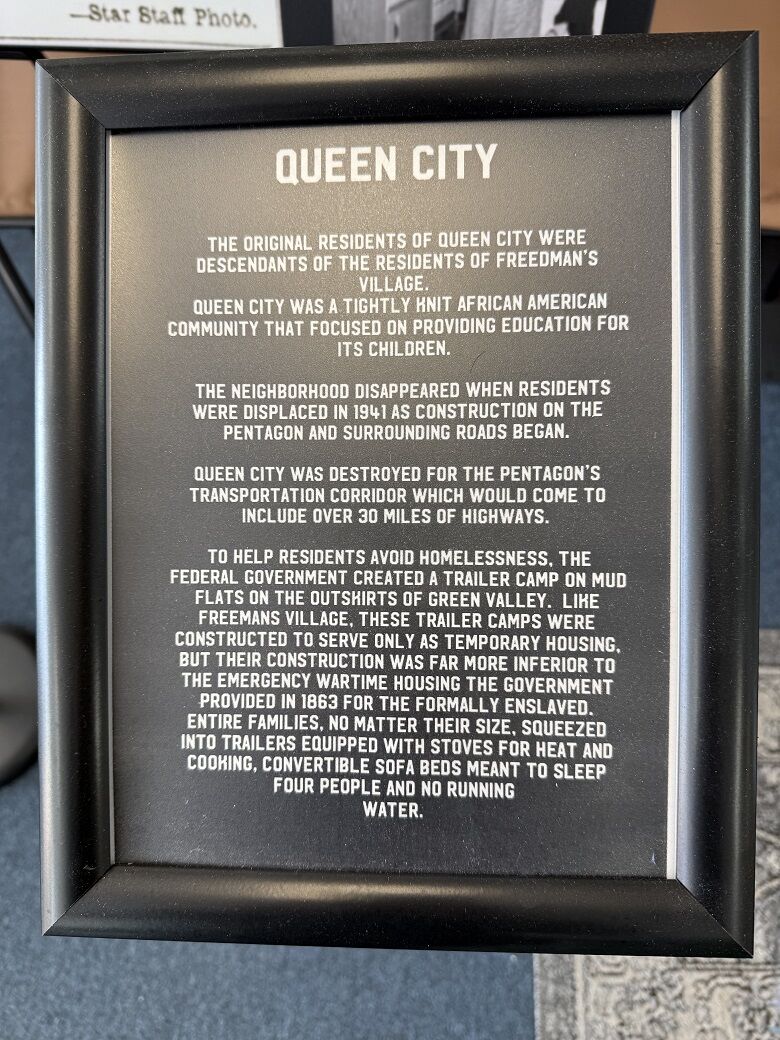

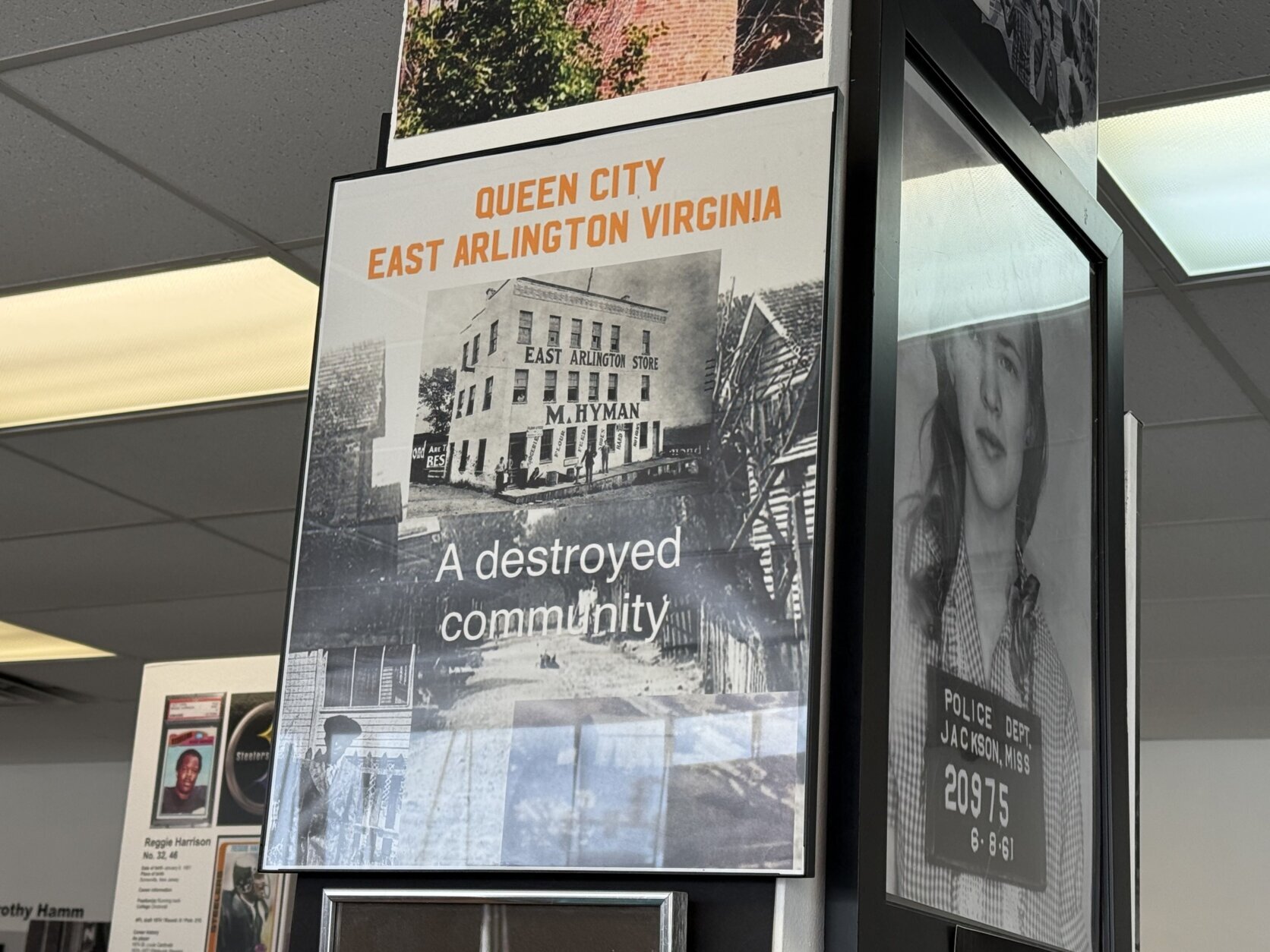

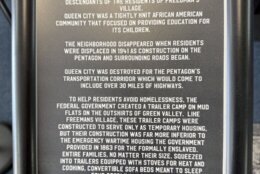

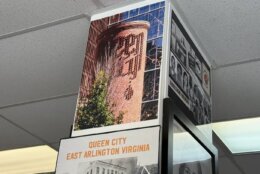

In the early 1900s, there was a once-thriving Black neighborhood in Arlington, Virginia, on land that was first owned by the Mount Olive Baptist Church. You wouldn’t know that by taking a look around the county today.

But at the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington, the memory of the Queen City community is being kept alive.

“We weren’t that many, maybe 100 years out of slavery when this neighborhood first began to grow,” said Scott Taylor, director of the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington.

Taylor said it was a proud community, which during the time of Jim Crow-era segregation and discrimination practices, had stores, its own barber and even was home to Arlington’s first all-Black fire department.

“They had to have that, because if something was on fire, no other fire department would come,” Taylor said, noting how fire stations established in white communities would not lend their services to Black neighborhoods.

According to the Arlington Library, a 1940 census revealed Queen City was home to 903 people who lived in 218 homes on the property.

Taylor said it was also a city which prided itself on education, with children attending nearby Jefferson School.

“This was a thriving neighborhood,” Taylor said.

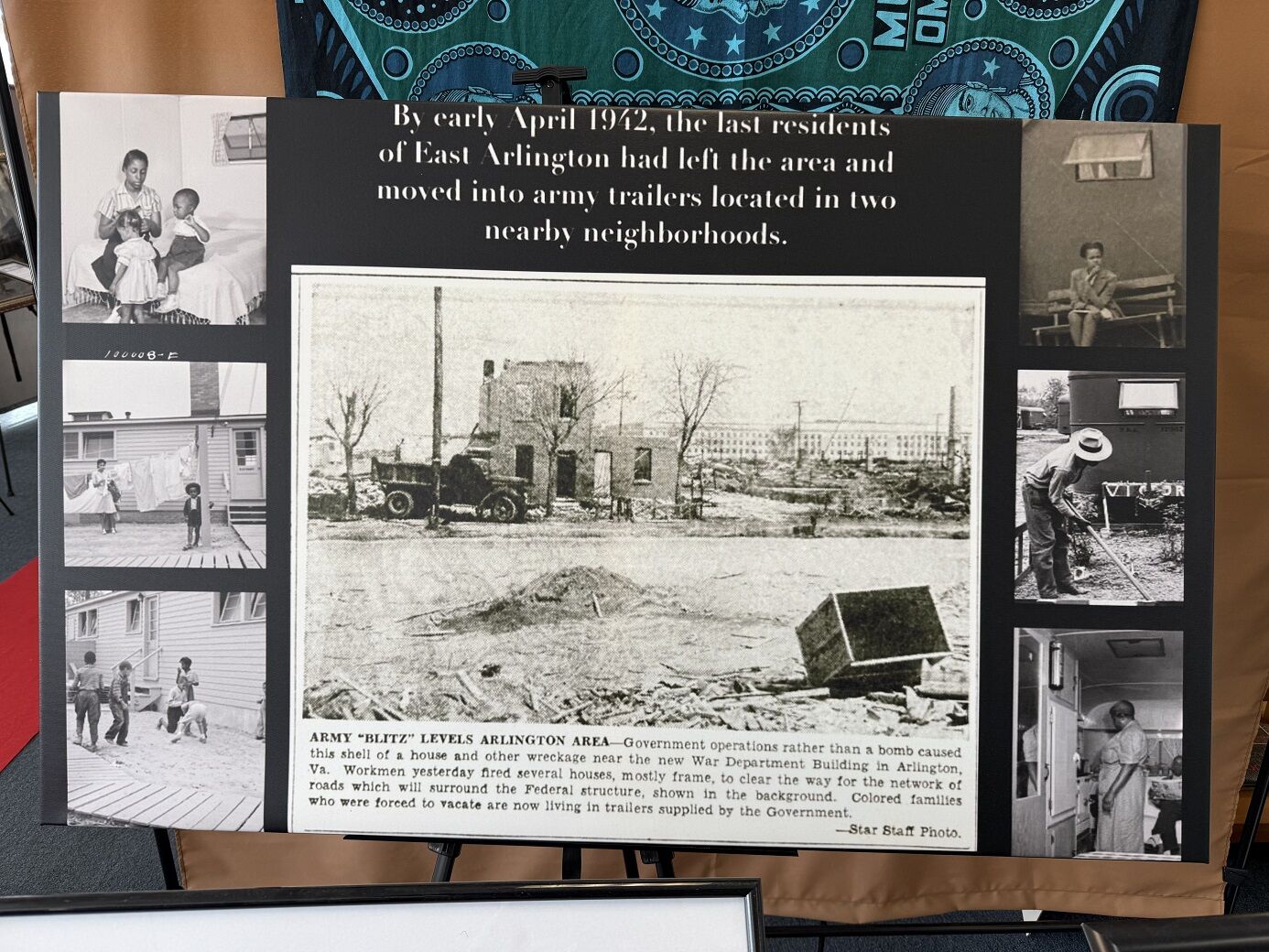

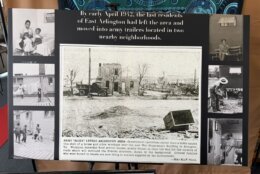

That would change in 1942, the year after construction of the Pentagon began.

Pentagon pulls eminent domain

A wrench was thrown into the community’s potential growth as the government used eminent domain to acquire the land for a transportation corridor that connects Columbia Pike to the Pentagon.

While residents knew they would be forced to leave their homes, they didn’t know when exactly the day would come, according to Taylor.

“You can imagine waking up one morning for your coffee and there’s a bulldozer next door, and you just don’t know what to do,” he said.

Taylor said one resident would pen a letter to first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, asking for help. That, Taylor said, would lead to trailers being brought in for displaced residents.

“Displaced people were put in a trailer camp for a couple of years, and the conditions were awful — it was worse than Freedman’s Village,” Taylor said.

The Freedman’s Village was one of many established during the Civil War that were meant to be temporary housing areas, and saw residents build schools, hospitals and social services to sustain their lives, according to the Arlington National Cemetery. In fact, many of Queen City’s residents were from the nearby Freedman’s Village, which was closed by the 1900s.

Rebuilding after Queen City

The museum director said the residents were resilient and would later settle in other Black neighborhoods in Arlington, among them Johnston Hill, Green Valley and Hall’s Hill.

“It just shows how these people knew how to make lemonade out of lemons,” Taylor said.

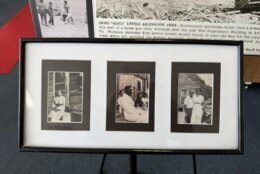

Taylor said his museum, which includes a photo exhibit that tells the story of Queen City, wants to make sure the town isn’t forgotten.

“People need to know some of the struggles that some of these people went through to make Arlington the beautiful, thriving county it is today,” he said.

The town of Arlington will provide a historical marker that will go at the Queen City site. In 2022, a brick art installation was erected at Metropolitan Park at Amazon’s National Landing, which paid homage to the lost town.

“There are a lot of people out there that are fighting to keep the history alive,” Taylor said.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2025 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.