At the oldest house in Arlington County, the Ball-Sellers House, three small bronze plaques were unveiled Saturday in a sun-dappled ceremony.

Each plaque identifies an enslaved person who lived at the house, one of the oldest houses in the entire D.C. region, built in the 1760s.

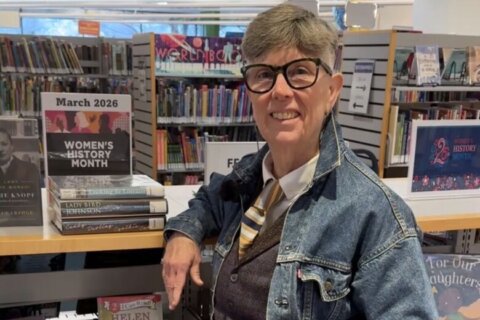

“The Ball family did not own slaves, but if I had to guess they probably hired them to help with the harvest … the next family that owned the house was the William Carlin family … the records don’t exist that tell us whether or not William owned enslaved people but when he passed away, his wife, actually was an enslaver,” said Jessica Kaplan, co-coordinator of the project “Memorializing the Enslaved in Arlington.”

Kaplan said a search of the 1820 census turned up references to two enslaved people, and a review of the 1830 census revealed one enslaved person.

“Then we were able to find the name Nancy, one of the enslaved women, who tended to Mrs. Carlin in her old age,” Kaplan said.

Each of the markers, created by public high school students, identifies an enslaved individual as best as records allow.

“We have been documenting all of the enslaved people that lived and worked in this county and we are hoping to place what we call stumbling stones and these are based on Stolperstein in Germany that are plaques that commemorate the lives of Holocaust victims,” Kaplan said.

According to Kaplan, searches of historic documents and records have so far identified more than 1,400 individuals enslaved in Arlington County — including the names of about 800.

An exuberant crowd of public officials, historians, neighbors, students and others gathered in the backyard of the modest farm house, its earliest section built nearly 300 years ago, and then walked to the front of the house where the plaques were unveiled.

“These are the first stumbling stones that are going to be dedicated and what we hope is a long line of stumbling stones throughout the county at the locations of enslavement,” Kaplan said.

Students at Arlington Tech High School, under teacher Jordan Kivitz, were tasked with engineering and fabricating the plaques.

“This project was a wonderful opportunity for all of us to get to learn not only the technical skills and the science and engineering that we all want to go and study in the future, but also learn about where we live, the people who used to live here and what they went through,” said Anna Litwiller, one of the students who helped make the ‘stumbling stones.’

Kaplan, who is a board member of the Arlington County Historical Society, said it is important to honor the lives and the contributions of the county’s past population of enslaved people, pointing to the three linked to the Ball-Sellers House.

“We’re talking about three people. Yes, we’ve got one that’s named and two that aren’t named and I just want people to reflect on these lives when they look at the stumbling stones and go, you know what? This happened in my backyard. It’s in my neighborhood,” she said.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article contained a quotation misstating the years associated with two census records. The article has been corrected and updated.