Arlington Public Schools in Virginia is proposing a plan that would enable middle and high school students to retake or redo certain assignments and reduce the weight that homework has on a student’s overall grade.

Under proposed changes to school system policies, all teachers would provide “retakes” and “redos” for all students on certain class assignments, and the higher grade would be recorded for the student. The change also calls for a decrease in the percentage of homework in the calculation of a student’s overall grade.

And, assignments turned in after the due date but before the end of a teaching unit would have to be accepted for credit, though a student may still be penalized up to 10% for the late submission.

The proposed changes, which also include tweaks to the elementary school standards-based grading policy, are part of Arlington’s new approach to grading that emphasizes equity.

The Northern Virginia school district has worked to pilot and implement equitable grading processes across the division. Nearby Fairfax County Public Schools, the state’s largest school system, is currently reviewing its high school grading policies.

Proponents of the shift in grading approach say it reduces subjectivity in grading and allows grades to accurately represent a student’s overall knowledge. Critics argue it doesn’t prepare students for college or careers after high school.

The school system is collecting feedback on the proposed changes this month, and expects Superintendent Francisco Duran to approve the updated policies in June, a spokesman said. They’d be in place for the start of the 2023-24 school year.

“I’m all for lowering pressure on students, for improving mastery, improving self-advocacy, strengthening social-emotional learning. It’s growth,” school board member Reid Goldstein said at Thursday’s work session. “I have heartburn and I am concerned about students in their post-APS life, as I said, believing that there’s flexibility in deadlines.”

School officials hope the changes will make grading more equitable, and provide more consistency from class to class and school to school. Middle and high school students would be graded on a scale from A-E, instead of A-F, and formative assessments, which include things such as homework, can’t account for more than 40% of a student’s quarter grade.

The county considered making 50% the lowest grade a student can receive on an assignment, regardless of if and when it’s submitted. Some teachers currently have that as part of their class grading policy, but school leaders said there wasn’t consensus about making it a requirement in the updated policy.

Some schools have already implemented some of the changes being considered. Keisha Boggan, principal of Thomas Jefferson Middle School, said not turning in an assignment or completing a task isn’t indicative of what a student does or doesn’t know.

“That is a work habit problem, not an issue with that student’s mastery of a skill,” Boggan said. The transition to the changes was tough, she said, because “most of us have grown up in systems where we were penalized for turning assignments in late.”

The school, Boggan said, realized students weren’t being given an opportunity to demonstrate their learning.

Under the proposed policy, if students want to retake an assessment, they’re required to meet with the teacher first. Anne Stewart, a social studies teacher at Yorktown High School, told the school board that the change has “had a tremendous impact on not just student grade improvement, but more importantly, an impact on student content knowledge and their skills.”

The changes, school leaders told the board, do require additional time for retakes and grading. So, they urged the board to be mindful about class size, among other things.

Keith Knott, a third-grade teacher at Innovation Elementary, said teachers aren’t often taught how to grade as part of their training.

“Grading is very subjective,” Knott said.

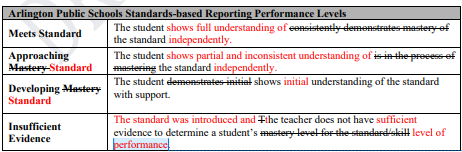

At the elementary level, 17 schools have shifted to a standards-based grading model, which uses terms such as “meets standard” or “developing standard” to evaluate student progress. Four more will be shifting to that model, according to Sarah Putnam, executive director of curriculum and instruction.

The county, Putnam said, will use data from a partnership with Crescendo Education Group, and metrics, such as failure rate, to evaluate whether the policy changes are effective.

Some of the proposed changes are included below.

More information about the policy proposals can be found online.