Turning a great idea into a wildly popular product is a dream for inventors, but historically, that challenge has been substantially more difficult for Black inventors.

One major hurdle, especially during the turn of the 20th century, was getting the credit for an invention.

“Patent protection for a lot of African American inventors was rather difficult to achieve,” said Rebekah Oakes, acting historian with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, located in Alexandria, Virginia.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, during America’s Industrial Revolution, getting a patent was important to protect an inventor’s idea.

Anybody with a good idea could apply for a patent, but even after receiving one, Oakes said Black inventors had a harder time getting a product to market.

“There were financial barriers, and, especially for African American patent holders, regarding their race,” Oakes said.

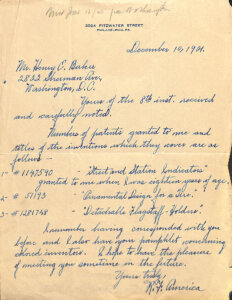

Henry Edwin Baker, a patent examiner who was Black, was instrumental in raising awareness about nonwhite inventors in the late 19th and early 20th century.

For years, as a second assistant patent examiner at the patent office, Baker compiled a list of Black patent holders.

Baker’s list, which to this day remains a key piece of the documentation of contributions of Black inventors, also struck a resonant chord of civil rights.

“Baker was part of an emerging civil rights movement,” Oakes said. “This list kind of pushed back against a very pervasive racist mythology at the time that African Americans weren’t creative, they weren’t inventive, and they couldn’t possibly invent something that was valuable to society.”

Oakes said Black inventors faced several disadvantages at the time.

“It was very difficult, sometimes, to get a patent attorney. It was difficult to pitch ideas to a commercial entity — someone who could take that invention and turn it into a commercial product,” she said. “Commercial entities would be a lot more likely to move forward with putting a product into manufacturing and then trying to sell that product to the public.”

First, Baker had to find the Black inventors who held patents. “He reached out to patent examiners, to attorneys, and community leaders, and he asked a simple question: ‘Do you known any African Americans who hold patents?'”

Since he worked for the agency that issued patents, one might think Baker could just look at U.S. Patent Office documentation.

“The patent office has never collected demographic information,” Oakes said. “There’s nothing to indicate whether someone is a particular race, or even a gender.”

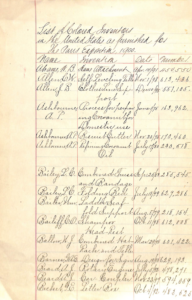

In 1899, amid the flurry of manufacturing, Baker prepared to spread the word about Black patent holders with an exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition entitled “List of Colored Inventors in the United States.”

“This list from 1899 was a handwritten list by Henry Baker, and it includes a little over 300 names,” Oakes said. “So, that’s about halfway through his researching time at the patent office.”

In 2023, the USPTO still does not collect demographic data, but external studies have shown underrepresentation of women and minority inventors named on patents. The agency’s Council for Inclusive Innovation aims to increase participation.

As part of its Black Innovation & Entrepreneurship series, the USPTO will be honoring Baker and inventors on his list, with the premiere of “America’s Ingenuity,” a documentary short focusing on the story of Richard F. America, one of the youngest inventors on Baker’s list who held three patents.

The documentary premieres on Feb. 24, at the Earl G. Graves School of Business & Management, Morgan Business Center, in Baltimore.