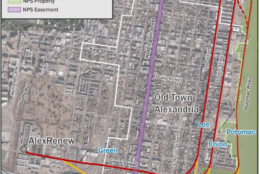

Massive digging is set to begin soon under Alexandria, Virginia, now that preferred options have been identified for tunnels meant to reduce the amount of raw sewage flowing into the Potomac River and its tributaries.

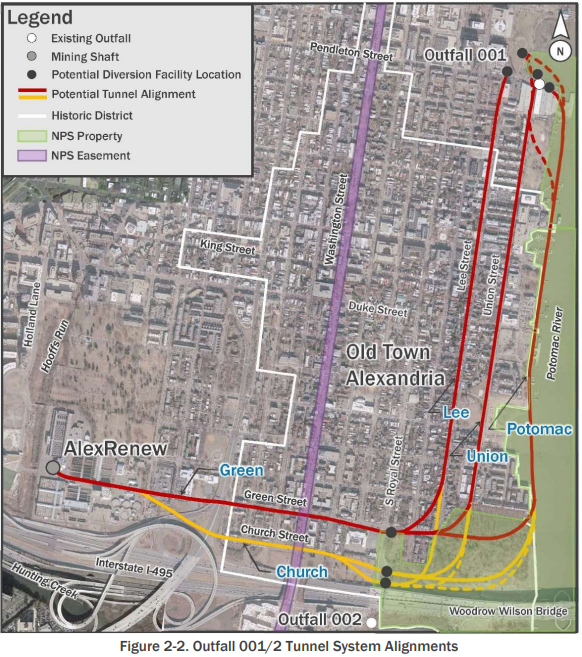

The environmental assessment released last week recommends digging a 19-foot diameter tunnel more than 10,000 feet long about 100 feet beneath Church Street and the Potomac River, just off the Old Town waterfront, that would connect to storage tanks at Robinson Terminal North and Royal Street.

The city would also build a diversion sewer along Hooffs Run with a storage tank bear Duke Street and S. Peyton Street.

“Community listening sessions” on the preferred alternatives are scheduled for Monday night at The Basilica School of St. Mary; Wednesday night at Charles Houston Recreation Center; and Thursday night at the AlexRenew Environmental Center.

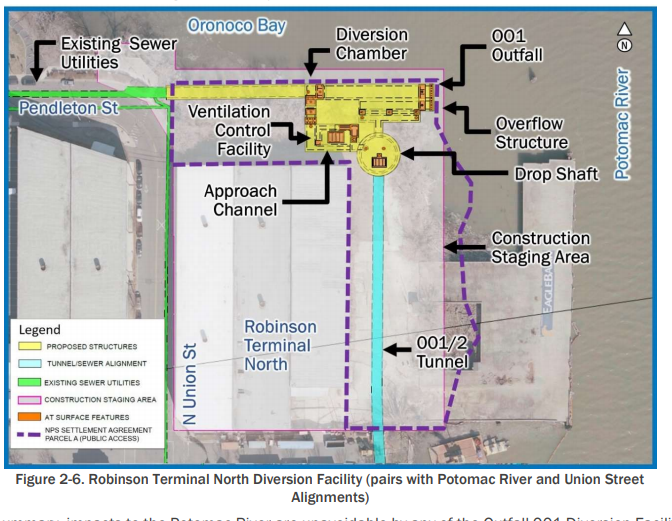

There are backup options for the Church-Potomac tunnel and Robinson Terminal North sewage diversion facility, depending on further research and negotiations with the private landowner, which could lead to the tunnel instead going under Church and Union streets, and the storage facility going on the east side of Oronoco Bay Park. Construction of those options could be more disruptive.

The Alexandria Planning Commission considers a Development Special Use Permit application for the tunnels Tuesday night.

In 2017, state lawmakers required the city to complete the project by July 1, 2025, to address regular overflows of four combined sewage outfalls linked up to a system that’s more than 100 years old.

The project is a main driver of sewage rate increases for Alexandria residents planned for years to come, including an increase of about $5 per month starting July 1.

In all, the project is expected to cost $370 million to $555 million.

Today, about 140 million gallons of sewage or sewage-contaminated stormwater flows into Alexandria’s waterways each year.

The proposed fixes are meant to cut the sewage flows by 98%, limiting them to four to six times per year in big storms based on current rainfall rates.

A similar project underway in D.C. has shown results for the Anacostia River.

Construction plans outlined in Alexandria’s environmental assessment would take two and a half to four and a half years.

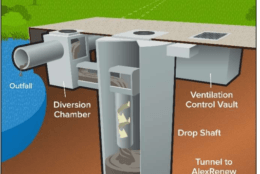

Though most of the work would take two to three years, the main mining shaft, which would include the lowering of a tunnel boring machine at the AlexRenew headquarters and the following tunnel boring work and construction of water treatment systems, would take an estimated four and a half years.

The tunneling, which is expected to be conducted around the clock, could have impacts on homes and other buildings above if the ground settles or there are problems with vibrations.

The environmental review promises all of those issues will be closely monitored, and that the preferred routes are meant to reduce those and other impacts.

“Surface settlements induced by tunneling are expected to be fractions of an inch over the tunnel crown, and approach zero at a lateral distance of approximately 100 feet from the tunnel centerline,” the assessment said. “Therefore, for planning purposes, a 200-foot wide buffer centered on the tunnel is considered reasonable for identifying structures and utilities that could potentially be impacted by construction.”

Work is scheduled to start in November 2020.

“Above-ground construction activities would comply with the City of Alexandria noise ordinance, or in accordance with any granted variances regarding noise levels, construction hours or lighting. It is anticipated that construction operations at the tunnel mining site would be conducted 24 hours a day and seven days a week; however, hauling of the mined material would be limited to approved hauling hours,” the assessment said.

The dirt and rock mined from the tunnels would be driven out of the city along Route 1 rather than the George Washington Parkway.

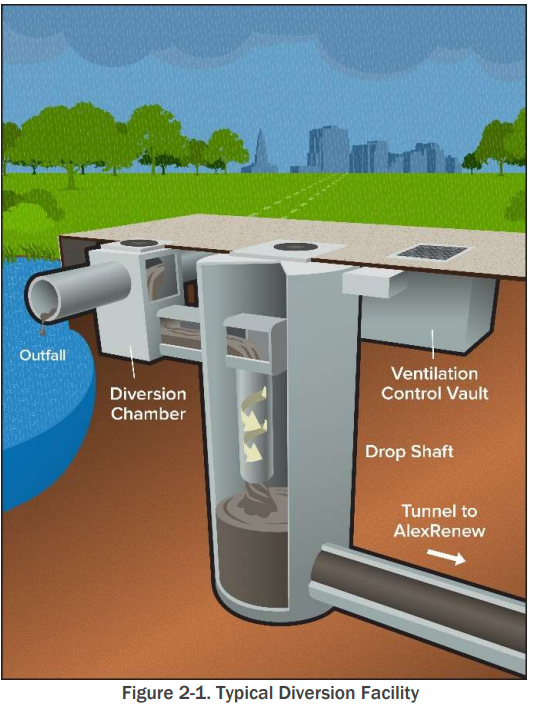

Once the system is built, there could also be some smelly moments in the midst of heavy rains. When sewage rushes into the empty overflow chambers, air is forced out.

At the two sites directly on the Potomac, the plan calls for “odor-control equipment … to mitigate the potential for fugitive emissions of odorous air.”