WASHINGTON — Capt. Florent Groberg would rather talk about his days at the University of Maryland than what he calls the worst day of his life.

“I saw something come out of his hand and it’s the last thing I remember. Whoosh — it detonates.”

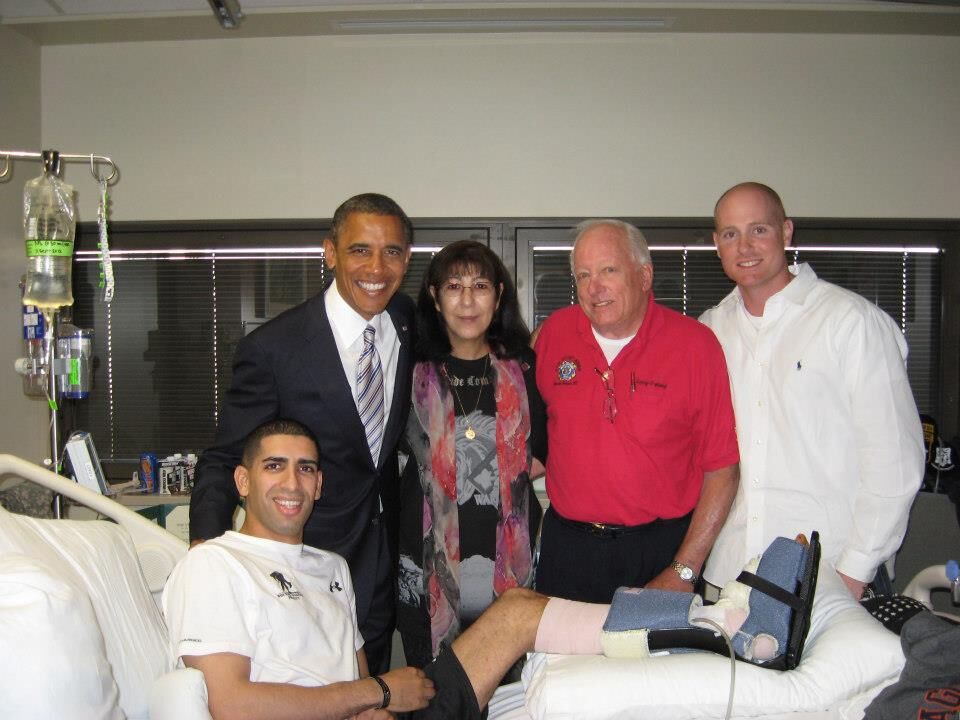

Thursday Groberg will receive the Medal of Honor at the White House. He nearly lost his leg in 2012 when he tackled a suicide bomber in Afghanistan. Four others died that day.

Sitting in an empty office room inside The Pentagon last week, the medically retired Army veteran sits upright in a light gray suit, recalling the faraway moment when the bomb exploded.

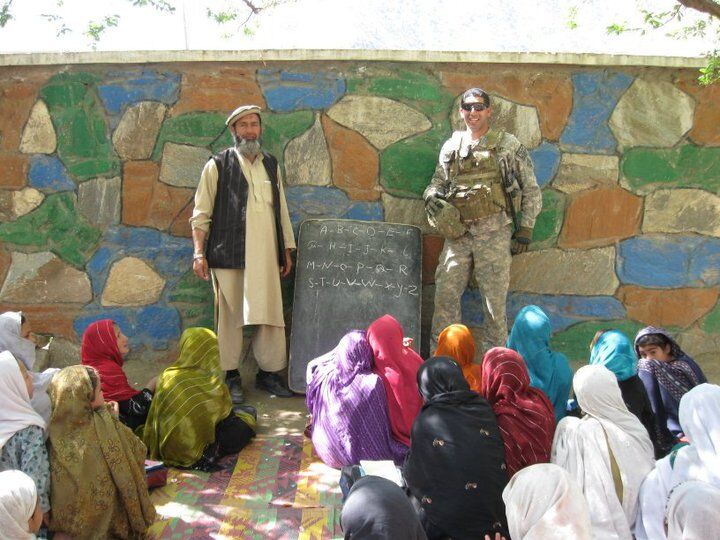

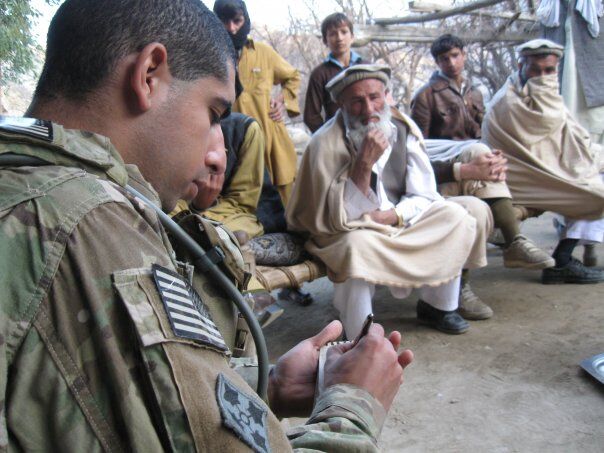

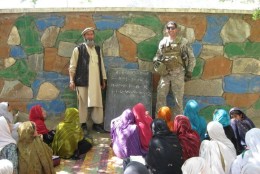

Aug. 8, 2012, started out as an average day. Six months into his second tour, Groberg and Sgt. 1st Class Brian Brink led a personal security detachment that was responsible that day for escorting then-Col. James Mingus, now a brigadier general assigned to Fort Carson, Colorado, to a meeting with an Afghan provincial governor. On their way to that meeting in Kunbar province, something changed.

“When we landed, it just felt weird. One of those eerie moments when you just it doesn’t feel right,” he recalls. So he changed his plan, reorganized his patrol and changed his position to lead the caravan on foot.

The first threat came as two motorcycles approached them and dismounted their bikes, potentially serving as a distraction. Then someone caught Groberg’s eye.

“As soon as he did a 180 and cut through our patrol, I left my position. I hit him with my rifle. I grabbed him and realized he had a suicide vest on,” Groberg says.

|

“This belongs to the four individuals we lost and their families. That’s it. I’m grateful and appreciative. But in my heart, in my own mind, this doesn’t belong to me; it belongs to them.”— Capt. Groberg |

As Sgt. Andrew Mahoney sprinted in to help, he and Groberg pushed the man back, trying to distance the bomb from the people they were trying to protect. They tackled him to the ground, and Groberg says the man dropped the “dead man’s trigger.”

Blast. White out.

When he came to, Groberg says, he was woozy. He looked down at his legs where the bomber had fallen.

“My fibia was sticking out. Leg was melting. I thought I stepped in an IED. And — ya know, I was obviously probably in the kill zone of an ambush. I was trying to get myself out, drag myself out,” he says of the chaos.

The explosion killed Command Sgt. Maj. Kevin J. Griffin, Maj. Thomas E. Kennedy, Air Force Maj. Walter D. Gray and Ragaei Abdelfattah, a U.S. Agency for International Development foreign service officer. It also caused a second suicide bomber to detonate his vest prematurely.

Brink told The Associated Press he came within a beat of shooting the suicide bomber but was forced to hold off when Groberg stepped in to tackle the man. Brink believes the casualties would have been far worse if he had shot the bomber, because his vest was facing the security detail.

“The scenario that we faced, somebody was going to die that day,” Brink said. “The way the events played out, it was probably the best possible outcome. Had I actually shot him, it would have been far worse.”

It was Brink who retrieved the badly wounded Groberg and carried him to the medic, while Groberg was briefed there were four casualties.

“They got me up and started dragging me and that’s when I saw the bodies. That’s when you’re like, ‘Damn. This is real.’ I don’t think you’re at the point of being sad. You’re at the point of being just so angry and devastated,” he says.

His thoughts often turn to the four men who did not survive the attack.

His recovery took the better part of three years and 33 surgeries at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

“In hindsight, I wish they would have taken my leg off! At the time, I was thinking, ‘Save my leg, save my leg,’ because, you know, I’m a runner and this is my passion,” he says.

Though he can’t run, Groberg periodically visits with young athletes at his alma mater, Walter Johnson High School, in Bethesda, Maryland, and other area high schools.

“I go back to talk to them about track and success and adapting to adversity and not giving up,” he says.

Groberg says he has found other passions and is focusing on what he can do. Foremost among them is honoring his personal pact to live for those four men and honor their families.

“The fact that they were able to embrace me after I was not able to protect their husband, that’s just to me, the most incredible and biggest honor,” he says of the fallen’s wives.

Members of each of the fallen men’s families will be at the White House to see Groberg receive the Medal of Honor.

Groberg will soon be the 10th living recipient of the Medal of Honor for service in Afghanistan, an honor he insists isn’t his.

“This belongs to the four individuals we lost and their families. That’s it. I’m grateful and appreciative. But in my heart, in my own mind, this doesn’t belong to me; it belongs to them.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.