WASHINGTON — True-life stories of dysfunction are hard to pull off, as filmmakers try to do the source justice without coming across as indulgent, all while convincing the masses to care.

This weekend, Jeannette Walls’ admirably honest 2005 memoir “The Glass Castle” becomes a star-studded family drama, chronicling the author’s rough upbringing with an unnecessarily complicated script by a rising director coaching redeeming performances.

Based on true events, the film follows New York City gossip columnist Jeannette (Brie Larson), who lives the big-city life with her yuppie fiance David (Max Greenfield). As her taxi transports her through the gritty streets to swanky parties and fancy dinners, she juggles suppressed memories of her eccentric upbringing by her nomadic, squatter parents, from her alcoholic father Rex (Woody Harrelson) to her imbalanced painter mother Rose Mary (Naomi Watts).

Having spent dozens of weeks on The New York Times best-seller list with nearly 3 million copies sold, it’s no surprise this attracted A-list talent, which is the best thing the film has going for it. For any of the film’s flaws, it’s always a treat watching stellar actors go to work.

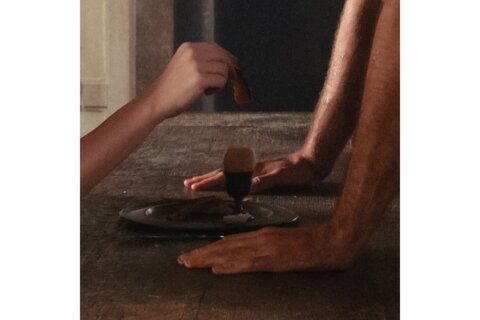

Watts plays her second neglectful mother of the summer, distracted by video games in “The Book of Henry,” then consumed by an art easel in “The Glass Castle.” Here, she ranges from aloof (letting her kids boil their own hot dogs) to intense (whooping at an arm-wrestling match). While we buy into her mental instability, her spacey portrait isn’t given enough room to rival Gena Rowlands’ force of nature in “A Woman Under the Influence” (1974).

Instead, the screen time goes to the undeniably charismatic Harrelson, who spits tough love and broken promises as he mocks up blueprints for a “glass castle” that never materializes. At times, we love Rex for his outside-the-box parenting akin to Viggo Mortensen in “Captain Fantastic” (2016). At other times, we hate him for subjecting his children to his personal demons with alcoholic outbursts, recalling Ray Milland’s detox in “The Lost Weekend” (1945).

It’s the children’s horrified faces that stick with us, from the adorable Chandler Head as the Youngest Jeannette to the show-stealing Ella Anderson as Jeannette ages 9 to 13. The latter looks like Brie Larson, who delivers a raw performance with scars bubbling just beneath the surface. Her cramped living spaces recall her Oscar-winning abductee in “Room” (2015), as does a scene where she cleverly escapes the unwanted advances of a pool-hall playboy.

Larson has become a muse for director Destin Daniel Cretton after the indie masterpiece “Short Term 12” (2013), which put them both on the map at South By Southwest. While that script felt organic — based on Cretton’s own experience with troubled teens at a juvenile detention center — “The Glass Castle” bears the burden of trying to tell someone else’s life story, resulting in a sanitized emotional distance to Walls’ heavy source material.

That’s not to say Cretton drops the ball behind the camera. “The Glass Castle” shows the continued maturation of a talented filmmaker with symbolic staging in some key scenes.

Consider the pivotal scene where Larson dines with her fiance’s parents. When the in-laws ask about her own embarrassing parents, she excuses herself to the bathroom where wallpaper vertical bars trap her as she tries to catch her breath. After a fond memory, Cretton cuts back to the bathroom, where stalls block the vertical bars, relaxing Larson and enabling her to re-emerge to the dining room and tell her in-laws the truth about her parents’ living conditions.

However, he gets into trouble by trying to juggle too much in the script. Co-written by Cretton and Andrew Lanham (“The Shack”), the screenplay becomes convoluted by repeated jumps between adulthood and childhood. Some transitions work with visual or dialogue cues; others feel forced and disorienting, taking us out of the story to the point that we begin to notice the run time, which is never a good thing.

It would have been better to tell the story in straight chronological order, starting with her childhood and moving into adulthood. Or, if Cretton absolutely wanted Larson throughout, it should have been a simple framing device at the beginning, middle and end, rather than cutting back and forth so often. As is, the structure feels more jumbled than it needs to be.

By the time we reach Cretton’s final camera push-in, the pat ending doesn’t quite feel earned. Forgiveness is certainly divine, as is the understanding that all humans are flawed, forcing us to take the bad with the good. It’s a satisfying conclusion on paper, but on screen, it’s tied into such a neat bow that it feels tonally at odds with the rough-as-hell upbringing she endured.

In the end, it’s the type of movie that could eek out a few acting nominations but is written too scattershot to vie for Best Picture — hence the August release. Still, it’s worth watching for its touching family moments and blinding life lessons, as Harrelson shares important nuggets of worthwhile wisdom: “You were born to change the world,” he says, “not just add to the noise.”

“The Glass Castle” may not change the world, but it’s a cut above the Hollywood noise. That’s a moderate victory for a heavy story that’s so inherently challenging on the big screen. The cracks may be showing on the glass, but the castle still stands as a testament to a resilient life.