COLLEGE PARK, Md. — Recent presidents developed norms about using their pardoning power: deploy it sparingly, approve applicants through an official process and delay controversial pardons.

In his first 18 months in office, President Donald Trump has abided by none of these rules.

Now that his former campaign chairman Paul Manafort and former lawyer Michael Cohen have been found guilty of financial crimes, analysts wonder: Will the president again buck his predecessors’ patterns and pardon these — or other — allies?

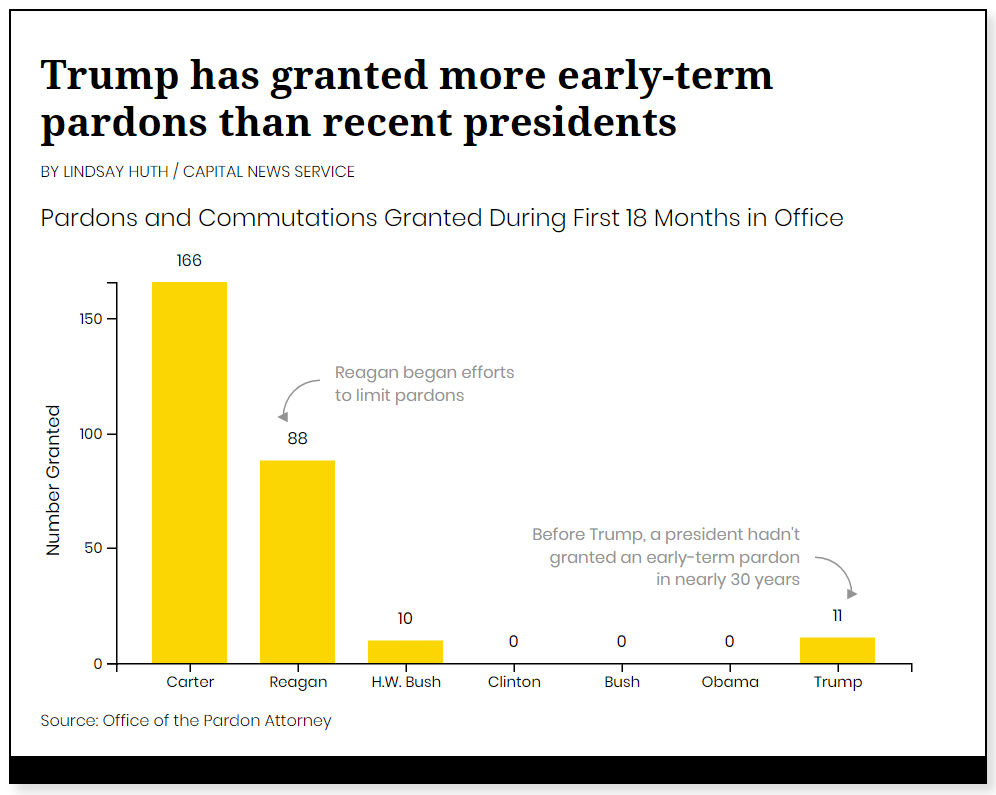

During his first 18 months in office, Trump handed out 11 pardons and commutations. A pardon absolves a conviction, while a commutation reduces or eliminates the punishment. The previous three presidents did not approve a single petition for clemency over the same period of their terms.

“At least for the last two to three decades, presidents have not used pardons very much during their first term,” said Jeremi Suri, professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “They wanted to avoid the appearance of any kind of corruption or quid pro quo.”

Before President Bill Clinton, presidents used early pardons more often, but they were generally directed toward rectifying unfair convictions or exceptionally long sentences, not helping officials or political backers, Suri said. During the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, presidents frequently absolved the convictions of civil rights or Vietnam War protesters, he said.

Pardons became less frequent under President Ronald Reagan, in part because he introduced the “tough-on-crime era,” tempering enthusiasm for pardoning criminals, said Andrew Rudalevige, professor at Bowdoin College.

In an effort to make pardons fairer, presidents also worked to standardize the petition process, funneling applications through the Justice Department, whose lawyers embark on a rigorous review process of each case before submitting lists of recommended clemency recipients to the president. President George W. Bush approved virtually no pardons outside this recommendation system, and President Barack Obama continued this practice into the early years of his presidency.

“It’s interesting that both W. [Bush] and Obama were trying to make the pardon, clemency, more for people who have been given these long convictions, not protecting political allies,” Suri said.

Trump’s early-term pardons are unusual, too, because he granted several to people who had not submitted petitions through this process.

Nine people have received acts of clemency from Trump, with two receiving both a pardon and a commutation. Of those nine, three — former Bush administration official Scooter Libby, conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza and Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio — had not applied for clemency before they were pardoned, the Department of Justice confirmed in an email. Another recipient, boxer Jack Johnson, had applied for clemency in 1920 and was pardoned posthumously.

Like Johnson, the other defendants Trump has chosen to pardon were involved in high-profile cases, or they used celebrities or the media to draw attention to their petitions. Trump granted Alice Marie Johnson a commutation after Kim Kardashian West advocated for her in a personal meeting with the president, and he pardoned Kristian Saucier after the petty officer first class of the Navy appealed his case on Fox News.

Trump has spoken publicly about previous and future pardons, another unusual tack for a president.

Sylvester Stallone called me with the story of heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson. His trials and tribulations were great, his life complex and controversial. Others have looked at this over the years, most thought it would be done, but yes, I am considering a Full Pardon!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 21, 2018

When he discusses pardons, he often speaks of them as acts of benevolence reserved for well-behaved citizens, Suri said.

“It’s a very paternalistic, mafia-boss way of talking about it,” he said.

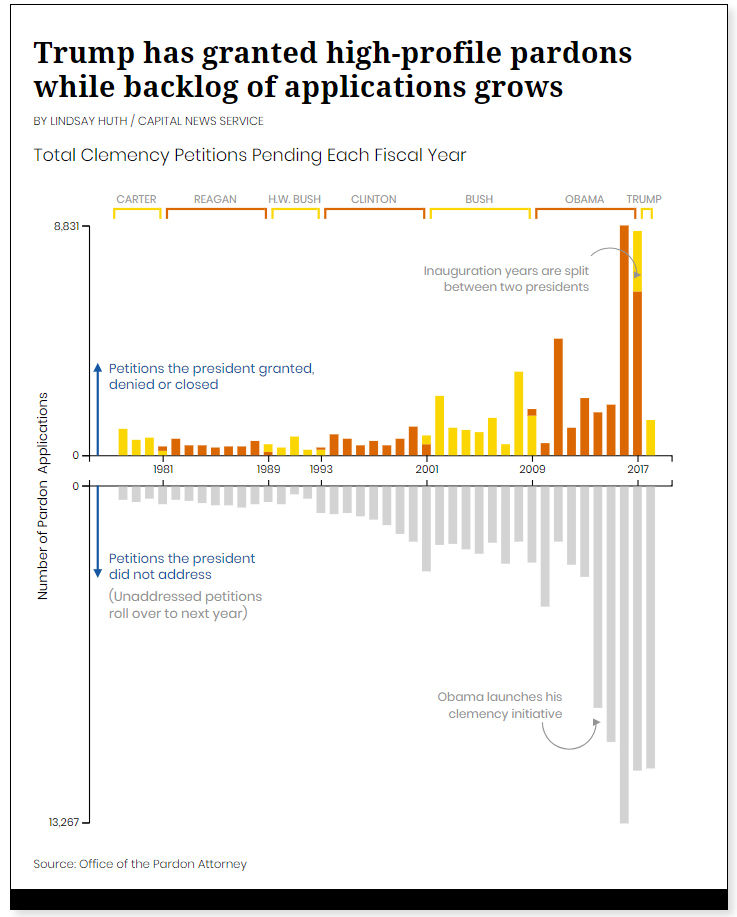

While Trump has granted select pardons and commutations outside of the review process, unaddressed petitions for clemency have piled up in the Office of the Pardon Attorney. The backlog spiked under Obama, who launched a clemency initiative in 2014 encouraging defendants convicted of minor, nonviolent crimes to apply for commutations.

More than 11,000 applications were pending at the end of June, according to the most recent data from the office.

By ignoring most of these applications and granting extraneous pardons, Trump is asserting one of his few unilateral powers as president, Rudalevige said. He particularly wants to demonstrate authority over the Department of Justice, his frequent opponent in public clashes, Suri said.

Rudalevige classifies Trump’s first pardon — that of Arpaio, the sheriff convicted of criminal contempt of court — as a signal to his political base, many of whom voted for Trump to support his hardline immigration stances mirrored by Arpaio.

“It’s aimed at reassuring people … that even though President Trump hasn’t been able to get all of his priorities through legislatively or in the budget, that he does have their backs on this issue,” Rudalevige said.

Trump has discussed granting clemency to other high-profile individuals like Martha Stewart and former Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich. The president has long criticized the length of Blagojevich’s sentence.

“It’s outrageous that Blagojevich goes to jail for 14 years when killers and sex offenders are out walking the streets. Is this justice … I don’t think so,” Trump tweeted in 2012.

Trump emphasized the injustice Stewart received, too, stating she was “to a certain extent … harshly and unfairly treated,” CNN reported in May.

But Suri said the president is using such pardons and commutations to establish his clemency power and obfuscate his true aim: to protect himself and his allies who have criminal evidence against him. That could include Manafort and Cohen.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller appears to be preparing for the possibility of a Trump pardon attempt by pursuing convictions in state court, where Trump lacks pardoning power, Suri said.

If Trump’s pardons follow previous presidents’ patterns, he will only grant more petitions as his term progresses. Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama each granted more petitions in the last 3.5 years in office than they did during their first four years combined, according to data from the Office of the Pardon Attorney.

“The political costs go down,” Rudalevige said. “It’s not a surprise that the most controversial pardons tend to come very, very late in a president’s term — almost the last day in some cases.”