WASHINGTON — The world’s most famous home movie continues to horrify viewers, fascinate and raise questions, but it also haunted the filmmaker until he died, his granddaughter said.

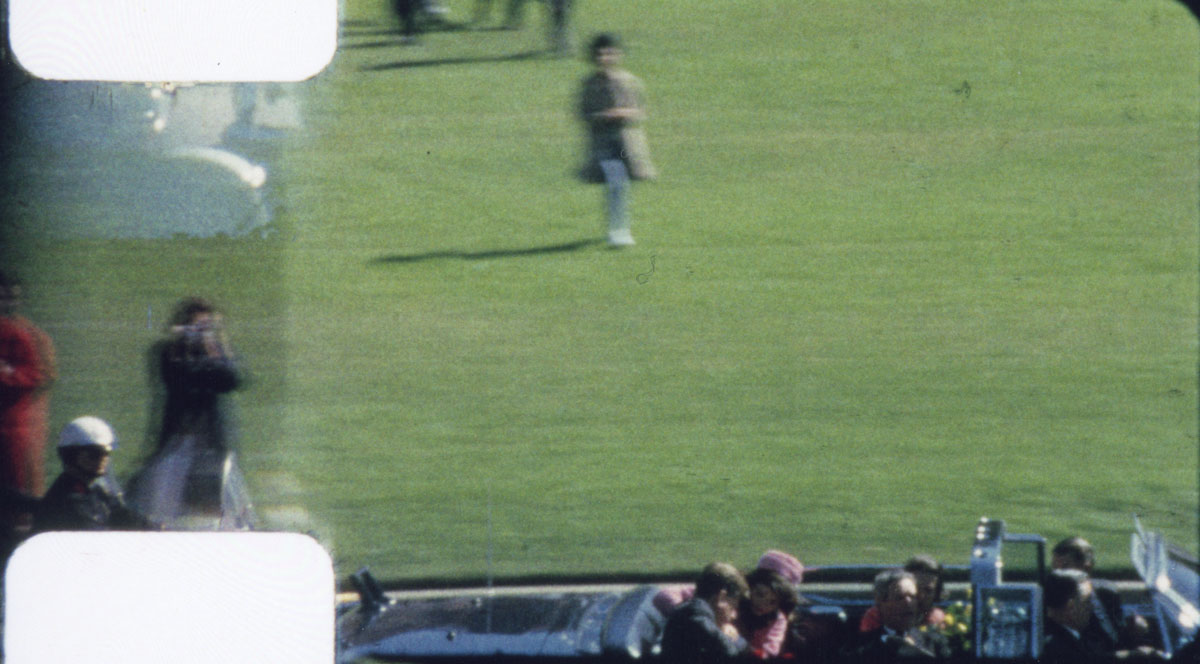

The 26-second silent, color film, shot by Dallas dress manufacturer Abraham Zapruder, consists of 486 frames of standard 8mm Kodachrome II safety film. Known as the Zapruder film, the movie captures the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, in Dallas, Texas, on Nov. 22, 1963.

Zapruder, standing on a concrete pedestal overlooking Dealey Plaza, began filming as Kennedy’s limousine turned onto Elm Street, moments before JFK was fatally shot by Lee Harvey Oswald, from a sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

In her new book, “Twenty-Six Seconds,” Zapruder’s granddaughter Alexandra Zapruder details the film’s effect on her grandfather, their family, the government, the media and artistic communities.

Zapruder said her grandfather, a fan of JFK, almost didn’t bring his new Model 414 PD Bell & Howell Zoomatic Director Series Camera to Dealey Plaza. After he and his assistant Lillian Rogers left his office to walk to Dealey Plaza, Rogers suggested he retrieve his camera.

“You really should go home and do this — this will mean so much to you to have it,” Rogers told Abe, whose family had emigrated from Russia when he was 15.

Abraham Zapruder began filming from the grassy knoll along Elm Street as the limousine carrying President and Jacqueline Kennedy, and Texas governor John Connally and his wife, Nellie, approached his vantage point.

“What he what he saw first is the president and the first lady in the motorcade coming around the corner and coming down Elm Street,” said Alexandra. “The first few seconds are just perfect.”

Zapruder’s view of Kennedy was briefly interrupted, as the limousine passed behind a Stemmons Freeway exit sign.

“When the president comes out you can see that something is wrong,” said Alexandra. “His arms are wrapped around his throat and he’s been hit, and then a few seconds later comes this terrible shot to the head.”

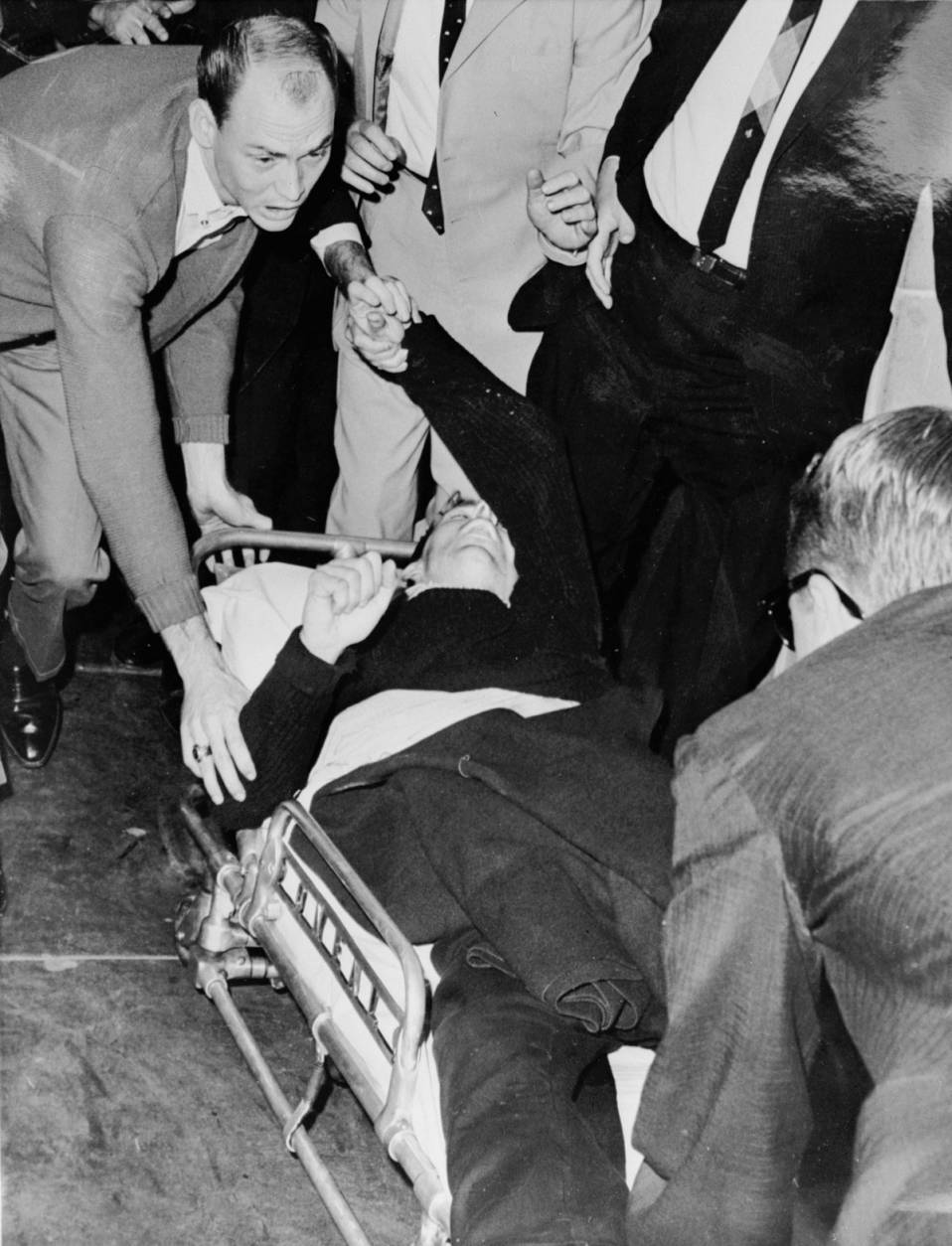

In years to come, Abraham Zapruder remained traumatized about what he had seen through his viewfinder.

“He witnessed this murder of the president, in real time, at close range,” his granddaughter said. “It was a moment that I think stayed with him for the rest of his life.”

Within seconds of watching Kennedy being shot, a distraught Zapruder was immediately approached by Dallas Morning News reporter Harry McCormack.

McCormack “wanted to know what he had on his camera,” said Abraham Zapruder’s granddaughter. “He said right in that moment, and continued to say for the whole day, that he wanted to get it in the hands of the federal authorities first and foremost.”

In her book, Zapruder explains the tug of war over the film in his camera, which included struggles to have it processed and duplicated so the Secret Service and FBI could have access.

Yet, the public didn’t see the Zapruder film, in its original form, for many years.

“Even though it was in the hands of the federal government that very evening, it was another 12 years before the American people saw it as a moving picture film,” Alexandra Zapruder said.

Abraham Zapruder sold the rights to the film to Life magazine the day after the assassination, for $25,000 a year for six years — a total of $150,000.

The magazine published still images from the Zapruder film.

“Life magazine had made an agreement with my grandfather that they would treat this film with dignity, that they would be respectful of the Kennedy family, that they wouldn’t exploit or sensationalize it, in any way, which was terribly important to my grandfather,” said Zapruder. “They honored that request, but part of what that meant was that they couldn’t show it as a film.”

In the years before digital publishing, Life magazine did not have a method of showing the film, said Zapruder. In addition, the publisher faced challenges in showing the moving pictures while maintaining its agreement with the filmmaker.

“There’s really no way to show the Zapruder film tastefully — that’s a contradiction in terms,” said his granddaughter.

While bootlegged versions of the film circulated within years of the JFK murder, most of the public had not seen it in its entirety when, in 1975, Geraldo Rivera aired a bootleg version on the late-night television show “Good Night America.”

Now, in the age of digital video, Zapruder says those who capture eyewitness video face some questions that are strikingly different, and some that are similar, to those her grandfather faced.

“In some ways the film represents the first thing of its kind — the first example of citizen journalism,” said Zapruder. “And it launched what now is so ubiquitous — cellphone camera videos of absolutely everything that occurs.”

Yet she believes the deep questions that plagued her grandfather in connection with his film should be asked today.

“Who records history? How do we decide what the American people should see or shouldn’t see? What is the effect of sharing certain things and so widely? How does it change our society?” Alexandra Zapruder said.

After Zapruder died in 1970, the public and media often weighed in on the Zapruder family’s attempt to maintain control of the original film, while sharing the images for research and investigation.

Eventually, after years of legal action over control of the original film, the Zapruder family sold the film to the U.S. government for $16 million.

“The original film exists; it resides in the National Archives,” said Alexandra Zapruder. “It is the property of the American people now, and we donated the copyright to the film to the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas Texas.”

Watch Alexandra Zapruder discuss “Twenty-Six Seconds”: