This article was reprinted with permission from Virginia Mercury.

Virginia’s State Water Control Board amended regulations last week that will require local governments in the same river basin to work together in crafting plans for water supply and use.

Previously, the state allowed local governments to choose whether they wanted to submit such plans independently or work with other localities in a regional approach. Plans must include existing water sources, water use and environmental conditions, any actions being taken to manage water supply and drought response plans, among other information.

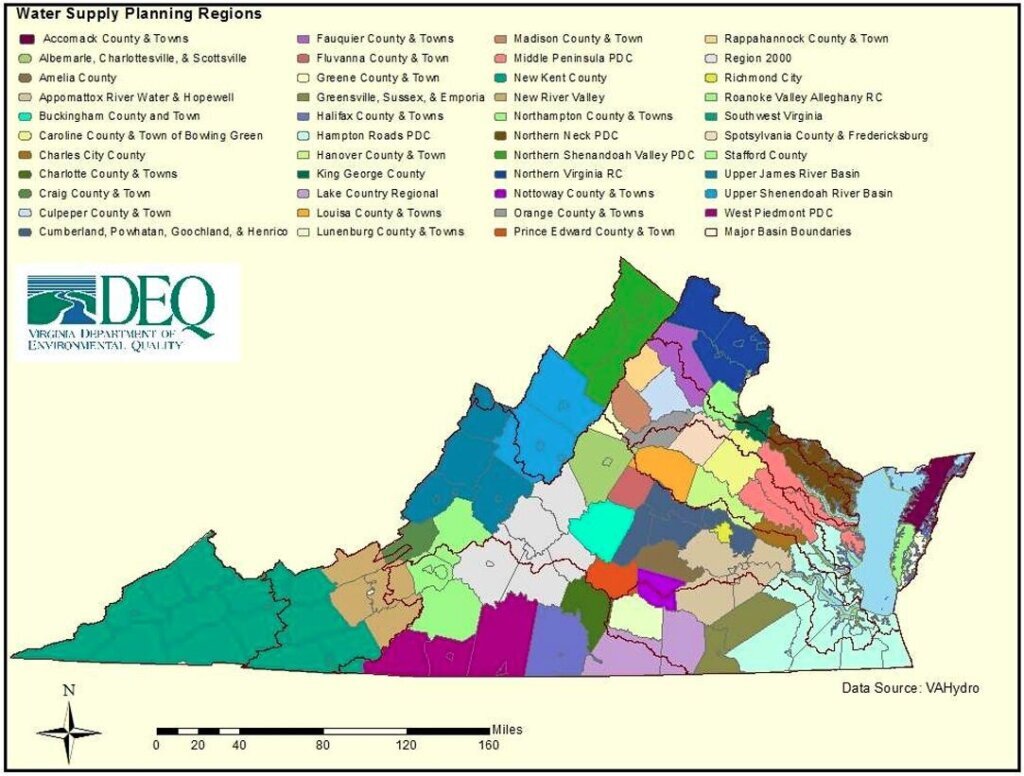

“These are true regional planning areas based upon river basin, common water supply sources or existing or planned water supply, cross-jurisdictional relationships,” said Weeden Cloe, manager of the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality’s Office of Water Supply at the State Water Control Board’s Nov. 30 meeting.

The changes to how Virginia handles water supply planning are a result of 2020 legislation from Del. Betsy Carr, D-Richmond. That law followed an earlier report by the Joint Legislative Audit Review Commission that found that “without regional planning, localities may miss opportunities to collaborate on high-cost water supply projects, and some localities may have greater access to water than others.”

A multiyear drought from 1999 to 2002 led to Virginia first requiring local water supply planning. In August 2002, DEQ stated that almost 100% of the state was experiencing “abnormally dry conditions,” with 28% experiencing “exceptional drought.”

The original rules allowing local governments to choose between a solo or group approach to planning led to the submission of 48 water plans, of which 10 were local and 38 regional, mostly consisting of one county and one or more city or town within the boundaries of the county.

However, concerns about water supply continued, particularly in the parts of eastern Virginia that rely for their drinking water on the Potomac and Yorktown-Eastover aquifers. In 2015, the General Assembly asked JLARC to review the state’s planning requirements.

[Read more: ‘Carrot and stick’ regulations aim to increase shallow aquifer use]

JLARC found that existing plans “have improved the state’s understanding of local water supply and demand, but they often do not include sufficient information to facilitate project development. Planning group boundaries do not adequately correspond to regional sharing of water use in river basins and subbasins.”

In 2020, Carr’s House Bill 542 not only required regional planning but directed that it be centered around river basins, areas where all water drains into the same larger river. The state has identified 14 river basins.

A two year stakeholder process to craft the new regulations culminated in 26 “manageable” planning areas, according to a meeting document.

The rollout of new groups overseeing those areas will happen over the next six months, Cloe said. Local governments can ask to be assigned to a different planning area if they can demonstrate a common water supply source, river basin or existing cross-jurisdictional relationship.

As part of the changes, new regional planning groups will be required to make a “reasonable effort” to coordinate with users that consume more than 300,000 gallons of water in a month. The National Environmental Education Foundation estimates the average Virginia resident uses about 75 gallons of water a day, or about 2,250 gallons of water a month.

The regulations apply to local governments’ planning for both groundwater and surface water sources, which constituted about 12% and 88% of reported water withdrawals across the state, respectively, according to DEQ’s latest annual water resources report in 2022. About 5.66 billion gallons of reported water withdrawals, or 77%, went toward cooling nuclear and fossil fuel power generation facilities that year.

The new regulations received support from local governments including Stafford County, which noted they provide clarity for small localities that don’t have preexisting regions, according to a summary of the last meeting.

Some concerns remain, however. The Friends of the Rappahannock, a grassroots organization that maintains the Rappahannock River, had expressed concern over the segmenting of areas around the waterway, particularly given increased pressure on water resources from new land uses, such as data centers. This year, the Rappahannock River hit a low mark for the century, the Free Lance-Star reported.

“Regional water supply plans need to take into account new land uses and industries that will use large amounts of water,” wrote Brent Hunsinger, tidal programs manager for the Friends of the Rappahannock, in a comment on the changes. “Demand for surface water withdrawal permits are increasing as reliance on groundwater is limited, especially in the Potomac Aquifer.”

The Virginia Municipal Drinking Water Association and other users have also worried about what they have characterized as a lack of clarity over how specific information should be incorporated into plans.

“There’s a long list of [risks],” Andrea Wortzel, an attorney with Mission H2O, a collection of municipal, industrial and agricultural water users, told the Mercury. “There are things like the … capacity of the waterway and how that impacts aquatic life and species. It’s unclear how a locality would assess that because that’s not really their typical domain.”

While Virginia has regional planning districts already in place for other purposes, such as decisions on development, the intent of the new water supply planning regions is to be “helpful,” Cloe said.

“It’s all going to depend on how these neighborhoods work together,” Cloe said. “I would hope that they would be able to put aside whatever differences they may have and work together collaboratively towards a better solution to the region.”