WASHINGTON — Almost four decades before Lloyd Lee Welch pleaded guilty in 2017 to two counts of first-degree murder in the 1975 deaths of Sheila and Katherine Lyon, the disappearance of an 18-year-old Radford University freshman led to Virginia’s first “no body” murder conviction.

The remains of the Lyon sisters have never been found, nor have the remains of Gina Renee Hall — the young woman voted “most popular” in her senior class at Coeburn High School, in southwestern Virginia — but prosecutors in the Lyon case were armed with something prosecutors in the Hall case never had:

A confession

Even today, prosecutors are often reluctant to try “no body” murder cases. The extra challenge presented by lack of human remains complicates their ability to convince jurors, beyond a reasonable doubt, of a defendant’s guilt.

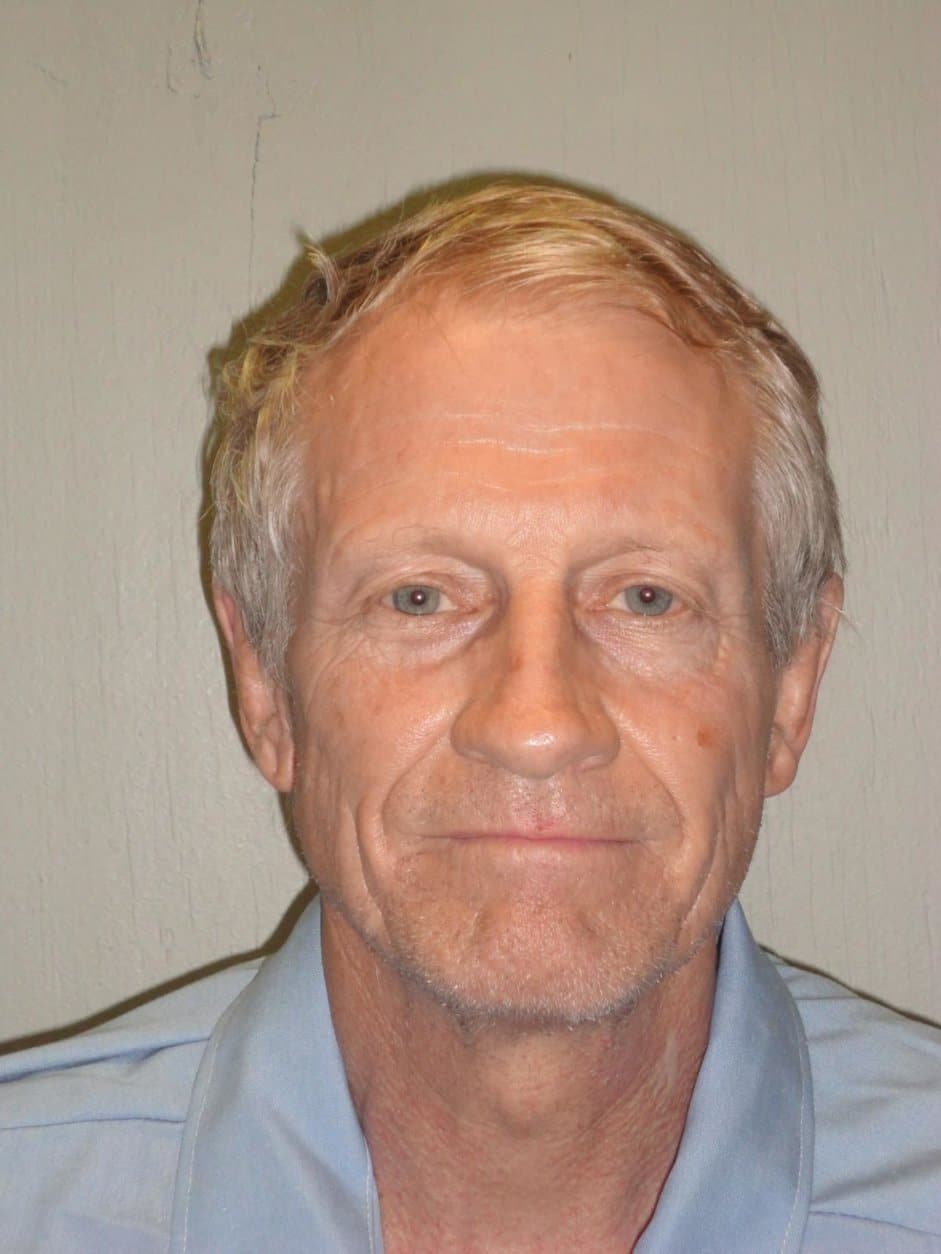

While prosecutors in the Welch case benefited from his admission, the defendant in Virginia’s first-ever “no body” case, Stephen Epperly, maintained — and continues to maintain — his innocence.

Almost 40 years after 12-year-old Sheila and 10-year-old Katherine were last spotted at Wheaton Plaza, Welch admitted to leaving the mall with the girls. That confession came in a series of interviews with detectives from Montgomery County, Maryland.

“With a lack of physical evidence, the Lyon sisters case would have stayed dormant,” without the breakthrough from Montgomery County detectives, according to Wes Nance, the Bedford County, Virginia prosecutor who convicted Lloyd Lee Welch.

“The statements they elicited from Welch developed over time into a series of partial confessions,” Nance said. “Without those statements, Bedford County never would have been in a position to charge him, period.”

Bedford County prosecutors alleged Welch burned at least one of the sisters’ bodies in a fire on the property of his family members on Taylor’s Mountain, in Thaxton, Virginia.

During more than eight interviews with Montgomery County detectives, Welch never acknowledged killing the girls, but he is still held responsible for their deaths under a 2017 plea agreement to felony murder.

Welch was sentenced to 48 years in a Virginia prison for the Lyon sisters’ murders, and later pleaded guilty to an unrelated series of sexual assaults of a Prince William County, Virginia, girl. He is currently serving time in Delaware for attacking the same girl while she lived in that state.

The former carnival worker will likely be eligible for parole after 25 years, when Welch will be in his 80s, although Nance said his likelihood of being granted parole is “very slim, if nonexistent.”

In 1980, prosecutors in Pulaski County, Virginia, in the southwestern corner of the state — without any admission of responsibility from the defendant — succeeded in the commonwealth’s first “no body” murder conviction, only the fourth in U.S. history.

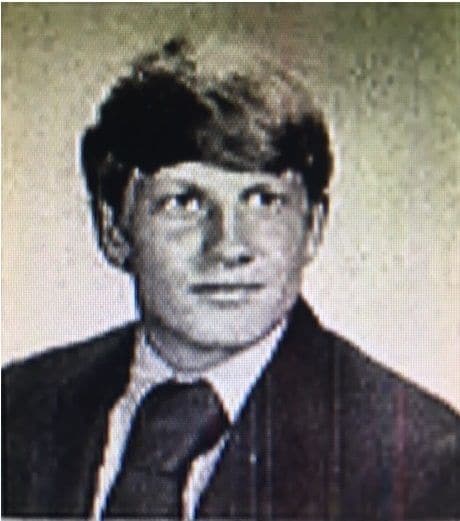

On June 28, 1980, Gina Renee Hall went out for a night of dancing at the Blacksburg Marriott Lounge, to celebrate completing her midterm exams at Radford.

She met and danced with 28-year-old Stephen Epperly, a former Virginia Tech football player. He left the club with Hall around midnight and drove her, in her car, to a secluded cabin at nearby Claytor Lake. She was never seen again.

“There was speculation he might have tricked or deceived her into thinking that a group of people from the nightclub were going to the lake house, when in fact his intention was to take her there in a one-on-one situation,” said Ron Peterson, Jr., author of “Under The Trestle: The 1980 Disappearance of Gina Renee Hall & Virginia’s First ‘No Body’ Murder Conviction.”

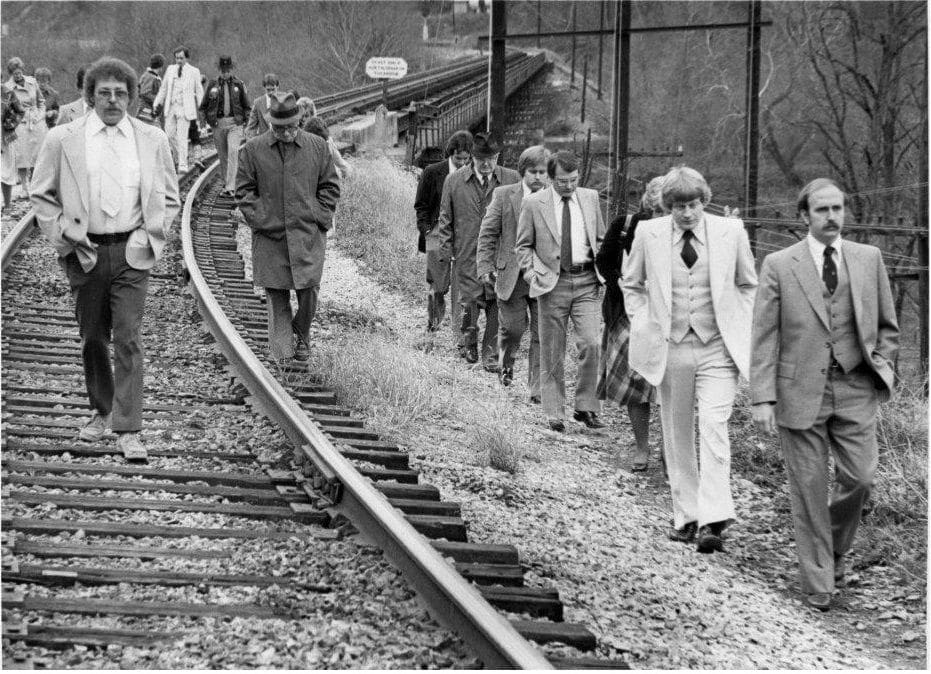

Peterson said Hall’s 1975 Chevrolet Monte Carlo was found Monday morning, abandoned under a railroad trestle.

“Gina was not in the car. The trunk of the car had been left open. Inside the trunk was blood and hair evidence, both of which were matched to Gina’s type,” said Peterson, although it was years after they recovered the evidence before forensic DNA testing became available.

Epperly told investigators he had made romantic advances toward Hall, but when she declined, she drove him home and they parted amicably.

“All the evidence pointed to Stephen Epperly, and everyone involved in the case was convinced of Epperly’s guilt,” said Peterson, who added that ‘everyone’ included Everett Shockley, the Pulaski County Commonwealth’s Attorney.

However, all of the evidence against Epperly was circumstantial — evidence that is admissible in court, but which leaves open the possibility of an alternative explanation.

“A lot of [Shockley’s] peers, and even a judge in the area advised him not to press charges against Epperly,” said Peterson. “The fear was, without Gina’s body, it would be hard to convince the jury to convict.”

“First they’d have to prove she was dead, and then have to prove that Epperly had killed her,” said Peterson.

On the strength of circumstantial evidence alone, Shockley risked his career and decided to prosecute Epperly.

“In early September, Epperly was indicted for first degree murder,” said Johnson. “In trial, Shockley called 31 witnesses and presented over 90 pieces of forensic evidence.”

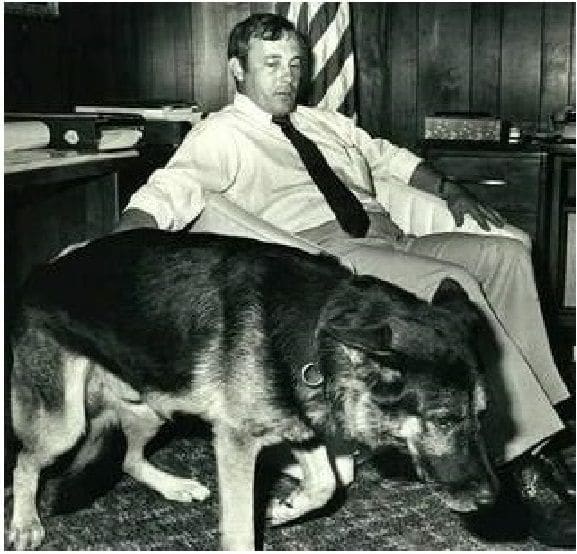

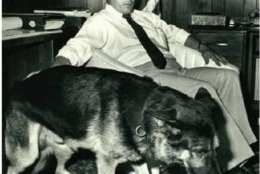

One of the most compelling witnesses was John Preston and his tracking dog. It was the first time in Virginia’s history that dog tracking evidence was allowed in court.

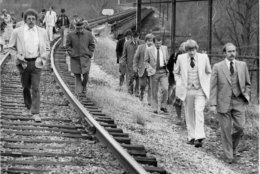

After being scented on a pair of Epperly’s underwear, the dog, named Harass II, led Preston — a retired Pennsylvania State Trooper — and detectives on a search for clues, starting at the spot where Hall’s abandoned car had been located.

“He followed the scent trail over the railroad trestle, across the river, followed a circuitous route through the town of Radford to the front porch of a house and stopped at the front door. When the dog handler asked ‘Whose house is this?’ investigators said ‘Our suspect, Stephen Epperly.’”

The jury deliberated two hours before finding Epperly guilty of murdering Hall and recommended a life sentence. Judge R. William Arthur concurred, and ordered Epperly spend the rest of his life in prison.

Thirty-eight years later, after several appeals of his conviction, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s declination to hear his case, Epperly has apparently run out of legal avenues. Still, he maintains he didn’t kill Hall.

“He has never admitted his guilt and has enthusiastically insisted on his innocence,” said Peterson.

Epperly first became eligible for parole in 1994. “Every three years he’s come back up for parole and been denied by the Virginia Parole Board, in large part because this is a person who continues to punish [Hall’s] family by not disclosing what he did with her remains.”

Over the years, Peterson said there have been several false alarms in which discovered remains in Pulaski County turned out to be other people or large animals.

“About 10 years ago, a current Radford detective, named Andy Wilburn, reopened the search for her remains. He re-interviewed witnesses from the trial, talked to old friends of Epperly’s, pulled up old maps of the area, and even got the help of Radford University professors, one of which is skilled in the use of ground-penetrating radar to find clandestine graves.”

Recently, investigators dug a site on Radford University campus, where they had reason to believe Hall was buried.

“Obviously they did not find her, but they’re continuing to look,” said Peterson.

“I’ve come to hope there might be one person out there who has one bit of information that could come to lead to finding Gina’s remains,” said Peterson. “Having gotten to know Gina’s family, and Lt. Wilburn, who’s reopened the search, I think that they share that optimism.”