WASHINGTON — About 50 years ago, two men brought innovations to their respective sports and rode their distinctive styles to glory. One became industry standard, while the other was all but forgotten.

Olympic high jumper Dick Fosbury’s unusual, backward takeoff was dubbed the Fosbury Flop. While he was mocked at first, his technique proved revolutionary and led him to set the new Olympic and American records while taking gold at the 1968 Summer Games. It was instantly copied and is now the model every aspiring high jumper follows as they learn the sport.

On the other end of the spectrum, Rick Barry brought his underhand, free-throw shooting to professional basketball around the same time. He too was derided initially, but his results — making 90 percent for his NBA career — spoke for themselves. But unlike Fosbury’s style, Barry’s was lost to time.

Why? Was it simply a matter of perception, of players being afraid of being mocked for doing something different? Is there some macho insistence against underhanded throwing, some aspect that threatens some fragile sense of masculinity that permeates the NBA but not professional track and field? Could it really be that professional athletes care so much about how they look that they’re willing to sabotage themselves and their team’s chances of winning?

Fosbury, who is a huge basketball fan and grew up watching Barry play, doesn’t subscribe to that train of thought.

“In basketball, you see kids expressing themselves,” he told WTOP. “Everyone has their own style, their own shot. I don’t think it’s anything about being macho. It’s about being fun.”

You would think success — and winning — would be all the fun a professional athlete would need to convince them to switch.

Barry’s career NBA free-throw percentage was the best in league history when he retired and is still fourth-best today, trailing Steve Nash, Mark Price and Stephen Curry by less than half a percent each. Barry led the NBA six times (and the ABA once) in free-throw percentage, hitting an astonishing 92.5 percent over his final five seasons. This despite being a 6-foot-7 forward, standing several inches taller than the men above him on the career list, all of whom were point guards.

But almost nobody shoots free throws underhand. This despite a growing rash of poor shooters from the charity stripe, particularly taller players. In the 37 seasons since Barry retired, 455 players who attempted at least 20 free throws have shot 50 percent or worse from the line. Of those, 103 have shot 40 percent or worse.

You’ll notice the word “almost” in the graph above. This season, Houston Rockets rookie Chinanu Onuaku became the first NBA player since Barry to do so. He switched to the technique after his freshman year at Louisville, where he shot just 46.7 percent with a traditional stroke. His percentage improved to 58.9 the next year. And now, in the NBA D-League, he’s shooting 73.3 percent, nearly up to the NBA league average of 77.1 percent.

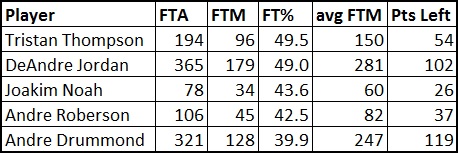

This year alone there are five NBA starters shooting under 50 percent from the line — Cavaliers forward Tristan Thompson, Clippers center DeAndre Jordan, Knicks center Joakim Noah, Thunder guard Andre Roberson and Pistons forward Andre Drummond who has converted just 39.9 percent of his 321 foul shots.

If they could only convert at the league average rate, they would add dozens of points to their teams’ totals for the year. Think about that in the case of Drummond, in particular. The 119-point deficit equates to 1.7 points per game. The Pistons, on average, are outscored by 0.8 points per game. They are currently tied for the ninth spot in the Eastern Conference, a game and a half out of a playoff spot.

There’s one major conference college player currently shooting underhand free throws as well, who thinks the stubbornness against the underhand form is insane. He just broke the consecutive free-throw streak for the University of Florida — which plays Wisconsin in the Sweet 16 Friday night — with 39 straight makes. Of course, that player might be biased, seeing as he is Rick Barry’s son, Canyon.

“Personally, I don’t care what people think because of the results,” Canyon Barry told the Tampa Bay Times. “They can make fun of me. I don’t know why other people, people in the NBA, don’t switch. People are willing to shoot 50, 55 percent from the line. Crazy.”

It does seem crazy, but perhaps more so to Canyon Barry, who grew up watching the master of the style in his own backyard.

But there has to be something else there. Both the Fosbury Flop and Barry’s underhand, free-throw style are more mechanically sound than the conventionally accepted alternatives.

The Flop keeps a jumper’s center of gravity lower to the ground, reducing the energy needed to clear the bar. Underhanded free throws are a more repeatable motion, with hands equally positioned on opposite sides of the ball. And they add far more backspin to a shot, giving it a softer landing should it hit the rim.

So why is it that of two incredibly successful innovations that were introduced into their respective sports at nearly the same time, only one was adopted? Fosbury thinks the answer is twofold.

“I kind of launched my technique in a huge broadcast at the Olympic Games,” he said, noting that the ’68 Games in Mexico City were the first to be televised in prime time back in the States. “And, of course, I won.”

Basketball’s more limited media market nearly five decades ago meant a far smaller audience was exposed to Barry’s prowess.

But Fosbury’s second point may be more resonant. Although future high jumpers picked up his style, it wasn’t until three years later that anyone tried it in a national competition. It was the next generation — not his contemporaries — that really ran with the flop. It wasn’t worth the risk for those who had spent their lives learning one way to suddenly try to switch. He believes the same is probably true in basketball.

“All of them grew up learning that overhead shot, or shooting from their chest,” he said. “They’ve invested hundreds or a thousand hours in the technique they had been taught.”

The Rockets’ Onuaku is seeing the hours put into his new technique paying off, and so is Barry. But will a couple of risk-takers willing to buck tradition even on the national stage of the NCAA Tournament and the NBA be enough to turn the tide? Will the preponderance of wayward, free throw-shooting Andres (Drummond, Jordan, and Roberson) be willing to follow suit, finally bringing the elder Barry’s revolution 50 years later?

“You need more than a couple successes,” said Fosbury.

More than that, you’ll need the humility of highly-paid NBA players to concede what isn’t working and try something new. If Fosbury’s example is any indication, that motivation may have to be internal.

“I didn’t do this for anyone else,” he says of his signature style. “I did it for myself.”