This is the second in the five-part WTOP special report Life on the Farm, an inside look at the not-so-glamorous world of Minor League Baseball. A new story will be published every Friday in July. Read Part I here.

WASHINGTON — On the way into a Major League ballpark, you’ll have to empty your pockets, maybe even remove your belt, and step through a metal detector while a security guard watches you enter. It’s not the most invasive set of measures, but it’s at least as intense as an airport screening was 15 years ago. If you don’t set the alarm off, you can regather your belongings, maybe grab a free playbill and shuffle into the game, one of up to 40,000 anonymous faces in the crowd.

On the way into a minor league park, you’re more likely to be greeted by a smiling face, even a handshake. If you’ve been to a game in Eugene, Oregon; Port Charlotte, Florida; New Orleans, or Round Rock, Texas, over the years, that face and hand may well have belonged to Jay Miller. And if you’d ever met Jay on a prior visit to the ballpark, he probably called you by name when you returned.

Over a 35-year career working in the front offices of minor and major league teams, Miller, 57, has helped his teams shatter attendance records and gained a reputation as one of the best executives in the game. That success has been built one handshake at a time, as he has continued the practice of greeting fans as they arrive and thanking them as they leave, no matter his position with the organization, his entire career. In an age of fewer and fewer face-to-face interactions, you can argue his approach is crucial.

“I don’t think you can do enough of that,” Miller says. “Let people know how important they are to the success of the franchise by being there.”

Miller’s voice has a naturally high timbre, lending it a quality that might seem inauthentic from someone else if it weren’t so obviously intrinsic to his nature. Despite his roots in Illinois, some syrup has dripped over his accent after more than 30 years in the South and Southwest, as he drawls his words out ever so slightly.

“It’s hard to believe that this is really a job I get paid for,” he told WINK-TV in 1988, when he was the 29 year-old general manager of the Charlotte Rangers, in Port Charlotte, Florida. “Because I enjoy it so much.”

All these years later, even after two stints in the big leagues, that joy still lives in his voice when he talks about what he does.

Front office size tends to correspond with the level of play, and, unsurprisingly, runs inverse to the amount of work required to make the operation function each day. The Nationals list more than 300 front office staff; the Orioles, nearly 200. At around 50, including their Ryan Sanders Sports Services, the Round Rock Express is about as big as minor league staffs get.

Miller played baseball in college, and when he graduated he just kept calling people in baseball until someone gave him a job. It didn’t matter that his first offer paid only $500 a month (plus commission), or that it meant moving halfway across the country to Eugene, where he was given the title of assistant general manager — a title that was much more glamorous than the job.

“I was hiring ushers and ticket takers, in charge of cleanup; I was doing all the stadium operations, working, selling,” he says. “I think full-time, back then, there were four of us.”

Miller worked in Eugene and in Salem, Virginia, then jumped to the majors when his boss, Larry Schmittou, was hired by the Texas Rangers. It was there that he personally handled all the ticket requests for one Lynn Nolan Ryan, Jr., forging a trust that would shape the rest of his life.

After two years in the minors, Nolan Ryan’s son Reid had retired from playing and was working part-time on the Rangers broadcasts when he decided he wanted to get into the management side of things at the minors.

“I decided I wanted to go out and start my own minor league baseball team,” explains Ryan. He says when he asked his father what he should do first, “He said, ‘Hey, you’ve got to call Jay Miller.’”

Ryan had known Miller since he was 17, largely through his father. That trust led him to install Miller as the president and general manager of the brand-new Round Rock Express in 1998. In 2000, the Express broke the Double-A attendance record, drawing better than 660,000 fans.

They continued to add to that total each of the next four years as Miller racked up awards, twice being named Minor League Executive of the Year by “The Sporting News.” And in 2005, Round Rock was promoted to Triple-A, an almost unheard-of development that indicated just how strong the franchise was. Miller earned the Minor League Executive of the Year award from “Baseball America” that winter.

“When you have him in a ballpark setting, whether it’s the fans or young kids coming out of college trying to get into the business, Jay always has time for them,” Ryan says. “He derives pleasure from helping his fellow man.”

Ryan and Miller worked together every day from 1998 until the fall of 2010, when Miller was offered a job as senior vice president with the Rangers, a team in which the elder Ryan held an ownership stake. During those 13 years, Reid Ryan came to understand the little things that separated Miller and made the fans of his team so fiercely loyal.

“I think the thing about Jay is, if somebody asked him to do something, a fan, whether it was get up for an early morning speech, come over to say hi to a friend, he’d do it,” says Ryan.

He says Miller once even installed a piece of wood next to a season ticket-holder’s seat to allow him to have somewhere to rest his drink.

So how, exactly, Jay Miller ended up in Sugar Land, working in the independent leagues, may seem something of a mystery.

The Sugar Land Skeeters play in the eight-team Atlantic League, which includes mostly teams along the Eastern seaboard, such as the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs. Their home ballpark, Constellation Field, is 20 miles due southwest as the crow flies from Minute Maid Park in Houston, where Reid Ryan is now the president of business operations. But it’s about as far as you can get and still be in the business of baseball.

“I was kind of just retired from the day-to-day thing and just consulting,” Miller says. “I loved the area, and I loved the staff, and I just decided to do it.”

Miller came to Sugar Land last fall, after a brief return to Round Rock from his time with the Rangers. A couple years ago, he may have thought he’d be living in his log cabin in Arlington. Instead, he’s in a condo across the street from the ballpark in Sugar Land, his cabin rented out to a professional player.

In a sense, this portion of Miller’s career resembles that of many of his players. Some arrive in Sugar Land for a second chance, hoping to get their way back to affiliated ball, to the big leagues. But most, in the backs of their minds, are just looking for a place to play, to be a part of the game, for an excuse to get paid to come to the ballpark every day.

Roger Clemens pitched in Sugar Land, for eight innings as a 49 year-old. Of course, so did Tracy McGrady, after the NBA star’s basketball career had ended and he decided to try his hand in another professional sport. Such is the balance of the independent leagues, which are generally more open to experimentation, but don’t want to lose their professionalism and become a circus.

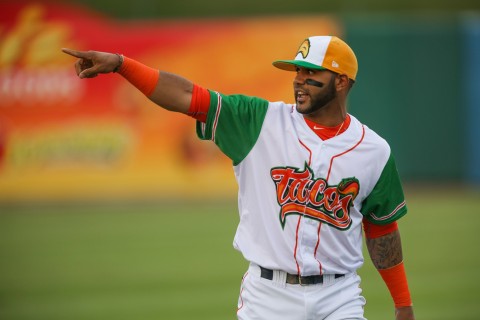

There are recognizable names on the team right now: former Orioles farmhand and first-round pick Tim Alderson, former Nationals reliever Ryan Mattheus, infield prospect Rick Hague. There’s Dan Runzler, who last appeared in the majors in 2012, and Sean Gallagher, who hasn’t been a big-leaguer since 2010.

“I think the level of play is Double-A, Triple-A, basically,” says Miller. “We get players who may not come to other places, but they’ll come here.”

One reason for that is Gary Gaetti. A 20-year big leaguer and two-time All-Star, he brings plenty of clout as the Skeeters’ manager. And while Miller may be helping out now with personnel decisions, it is Gaetti who brings in and signs players.

“He knows a lot of people,” says Miller. “He can make a phone call and get you signed (with a Major League organization), basically…If they have a need, they’ll call him up and ask him for help.”

Like seemingly everyone, Miller had already known Gaetti for 20 years before he got to Sugar Land; he was a coach during Miller’s stint in New Orleans.

“I really liked New Orleans, just the people,” Miller says. “The people were so good there. I made some lasting friendships there.”

Miller, as he’s shown, cares the most about those relationships, with the fans as well as his fellow front office members. And despite all the success he’s had elsewhere, he’s found the highest concentration of that secret sauce in independent ball.

“I think it’s the best staff I’ve ever had in baseball here in Sugar Land,” he says.

It’s proof that his methods are still effective, that his personal touch still works, even as the world becomes less and less personable around him.

“No matter where Jay’s been — in New Orleans, Round Rock, Arlington, or now in Sugar Land — the same thing is true,” Ryan said. “He makes a lot of lasting relationships, and treats fans like they are a guest in his home.”

Now, as Miller says farewell to fans every night, he can join them on the way out the door, just steps from his actual home, right across the street.

Part I: The road well-traveled

Part III: Minor league Moneyball

Part V: The unwitting translator