This is the first in the five-part WTOP special report, Life on the Farm, an inside look at the not-so-glamorous world of Minor League Baseball. A new story will be published every Friday in July.

METAIRIE, La. — The life of a minor league broadcaster may seem like a dream: Show up to the ballpark every day and get paid to watch and talk about baseball, right? The reality is rarely that simple. Most broadcasters earn their keep in other ways, working in media relations and selling advertising and tickets for the team. And in rare instances, they do each of these things as well as manage team travel.

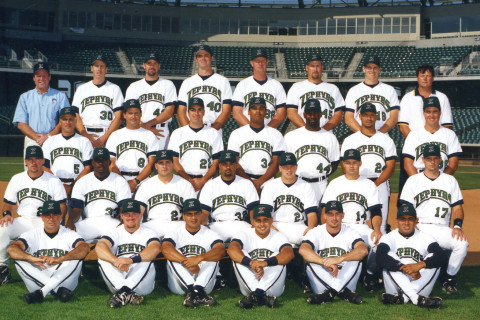

Tim Grubbs is in charge of all of the above. Even at the Triple-A level, where front office staffs are the most robust, his job responsibilities blur into all aspects of the business. He’s been the broadcaster for the New Orleans Zephyrs, a Miami Marlins affiliate, since 2002, and the full-time travel director since 2006.

In the major leagues, every team has a traveling secretary — someone who manages the charter schedule, the buses to the ballpark, the meal money, player requests from the inane to the opulent. In New Orleans, Tim handles all of that, along with game notes and recaps on the road, and then calls a three-hour game in between, jetting to a new city every four days.

With a life constantly in motion, comfort is defined by familiarity within the changes: The oddly-soft water from the hotel shower in Omaha. The breakfast burritos in the Denver airport, where the team often has to catch a connection. The green chile that smothers most everything in Albuquerque.

When a normal person with a normal job tells you that they have a hobby such as visiting places featured on Diners, Drive-ins and Dives, you think to yourself: That’s cool; they’ve probably been to a half-dozen spots, maybe even a double-digit number.

As Grubbs digs into his shrimp po’boy from Russell’s Short Stop, just down the street from Zephyr Field, he says, “I see [a place] on the show [and think], ‘It looks good; let me try it out.’ So, I’ve been to, like, 65 of those.”

Grubbs has the kind of affable, consistently upbeat personality that can help carry a listener through the dog days of another 144-game season. Or the kind that comes in handy when half the team is held off a flight from Memphis to Denver due to a glitch in the ticketing system — like they were this Wednesday, en route to Colorado Springs. The team got to the airport in the early morning, well in advance of departure, and made it through ticketing and security all the way to the gate, but 14 players did not get to Denver until midnight.

The good news? It was an off day, so no game was compromised. Unfortunately for the players — and Grubbs, who waited behind with them — it was the team’s only off day in a span of 32 days.

The Pacific Coast League — which, despite its westward-sounding name, includes New Orleans — is widely considered the toughest travel league in all of professional baseball.

It stretches from the Big Easy as far northeast as Nashville, up to Des Moines and Omaha, then all the way to Tacoma, Washington, before sweeping down California through Sacramento and Fresno and hooking through southwestern cities such as Albuquerque, El Paso and Austin. The geography means bus trips, the norm at the lower levels of baseball, are few and far between. And there are no cushy charter flights — all air travel is commercial, rarely involving nonstop flights.

There’s only one bus trip from New Orleans, a six-hour haul to Memphis. The only nonstop flight is to Nashville.

If you or I miss a connection while traveling, it might cost us a half-day of vacation. If the Zephyrs miss one — like they did when American Airlines didn’t hold a flight from O’Hare to Omaha in 2009 — chances are they miss the game that night. The team started the day in New Orleans, but some players had to fly from Chicago back to Dallas to connect to Omaha. Grubbs left his house at 4 a.m. that day and arrived in Omaha at midnight.

On the official game log for that season, the May 7 Zephyrs-Royals game is listed as postponed, with the reason listed as “other.”

“When you think about all the moving parts, with all these teams traveling, it’s amazing it doesn’t happen more often,” Grubbs says.

More often, the equipment doesn’t make it. On a road trip in 2007, pitcher Mike Pelfrey’s personal bag didn’t make it to the ballpark in time. Normally, that’s not a problem — all the baseball gear is prioritized. But Pelfrey’s contact lenses were in his own bag, and without them he couldn’t see the catcher’s signals. His start had to be pushed back.

For one game in 2015, the umpires’ equipment didn’t make it.

“We got an alternate umpire to do the plate, because he had his gear,” Grubbs recalls, but that only took care of part of the problem. “The three PCL umpires … we went up the street to a sporting goods store and bought them black pants and shirts.”

Such stories are commonplace. Like the time the batting helmets never made it to Fresno, so the navy and gray-adorned Zephyrs wore the Grizzlies’ old, black helmets from the year prior, dug out from storage, the color close enough that it was likely only noticeable to someone like Grubbs, who already knew, calling the game from his perch in the press box.

It’s an odd sight, watching 25 or so professional baseball players milling around a gate and filing onto a commercial plane together. Unlike college teams, they avoid any markings that suggest the team they belong to, often answering any questions from the surrounding public as to who they are with the most elaborate lie they think they can get away with (a traveling group of models, professional bull riders, etc.). All their equipment bags, with the team logo emblazoned upon them, are down in the belly of the plane.

Most people remember when airlines didn’t charge for checking bags. It’s become an inconvenience for personal air travel, but usually costs no more than $25 or $50. When you’re flying an entire baseball team and all its gear, those numbers increase dramatically.

Nobody was prepared for the charges when they started a little over a decade ago. At the time, the Zephyrs were still an Astros affiliate, and when Grubbs arrived at the airport, he was given a stunning, four-figure bill, not knowing who was going to be responsible for it.

“I remember getting on my cellphone and calling our old GM saying, ‘Hey, they’re charging us $3,800 for the equipment, what should I do?’,” Grubbs said. “And I had to step up and put my credit card down.”

At the lower levels, bags are packed onto buses. But in the PCL, where air travel is standard, costs range anywhere up to $60,000 per team, per year, just to ship bags. The Marlins cover half of the shipping cost, as many but not all Major League teams do. It’s a burden every team in the Pacific Coast League shares.

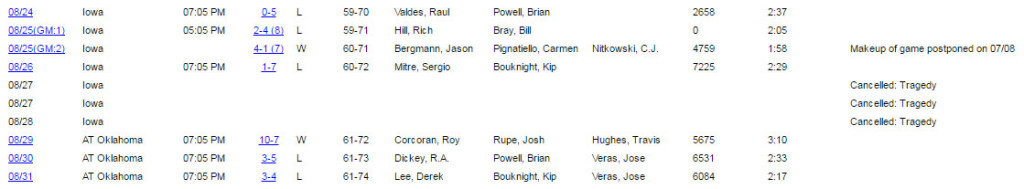

But living in New Orleans, one story is different. It’s the one everyone knows — the reason the 2005 home season was cut short, simply and hauntingly listed in the game log as “tragedy.”

In New Orleans, no conversation of any real length or depth seems untouched by Hurricane Katrina.

Zephyr Field is to the west-northwest of the city in Metairie, far closer to Louis Armstrong International Airport than to the French Quarter. The ballpark sits on higher ground, away from the levees that broke, flooding the city during Katrina. But gale-force winds still did about $1 million worth of damage, even lifting a scoreboard panel and dropping it into the seats.

The team played a home game Friday night, Aug. 26, 2005, with a doubleheader scheduled for the following day.

“In the middle of that game the news broke that Katrina had turned and it was a Category 5 storm headed into the Gulf and our way,” Grubbs says.

But there had been warnings of storms before that fizzled out as they reached Louisiana, or turned away from New Orleans. The team had a postgame fireworks show that night, and Grubbs went out for a couple of beers afterward. When he woke up the next day, the team had already planned to kill the second game of the doubleheader. By the time he reached the ballpark, the first game had been called off too, as he scrambled to book charter buses to drive the club to Oklahoma City.

The team actually played that Monday in Oklahoma City, the day the storm hit.

“I didn’t broadcast the game, because there were no radio stations back here,” Grubbs says. “So I just sat in the press box and chilled, thinking, ‘I’ll be back on the air tomorrow or the next day.’”

Obviously, that didn’t happen. The season ended on the road in Des Moines later that week, but nobody was allowed to fly back to New Orleans, the whole city shuttered amid disaster relief. Instead, airlines allowed stranded people, like Grubbs and the team, to transfer tickets to fly wherever they needed to go to stay with family.

Grubbs went home to his parents’ house in Pittsburgh and waited. Players left their cars, which were towed to another part of the stadium parking lot, as the National Guard used the grounds for rescue efforts. Many didn’t pick them up until Christmas.

“Really, at that point, I wasn’t sure if I’d ever move back here,” Grubbs says. “What about my job? What about Opening Day next year? All of those thoughts ran through your head for the next week or so.”

Finally, in late October, he was able to fly to Baton Rouge and drive into town to check on his apartment near Tulane and grab more clothes than the eight-day rotation he had cycled through since leaving.

“When I first came back in to check my apartment, a National Guardsman came with me,” Grubbs says. “It was a crazy time.”

Every travel director has that one city they can’t stand, in which something always seems to go wrong. For Grubbs, it seems to be Des Moines, one of the toughest to get into and out of from New Orleans. It’s where Pelfrey’s contacts were lost, where Grubbs was stranded when Katrina hit.

But it’s also where he met his wife, Emily.

The night the storm hit, he was out after the game with friends from the Iowa Cubs when they struck up a conversation with the table next to them. She didn’t believe he, with his blond hair and lingering Pittsburgh accent, was actually from New Orleans. He showed her his driver’s license. The rest, as they say, is history.

Katrina chased away some of the Zephyrs staff, including the primary travel director, after the season. Grubbs and a half-dozen other employees were put to work by the team owner at a golf course he owned in North Carolina, where they stayed in a hotel until they could all return to the city. When they did, Grubbs took over travel full-time, though it was only supposed to be for a year.

But a year later, it remained his reality. And after a year of long-distance dating, Emily joined him in New Orleans. They eventually bought a house closer to the ballpark. The life constantly in motion took root.

Part III: Minor league Moneyball

Part V: The unwitting translator