It’s not easy to photograph something that’s visible for only a few millionths of a second. So, when Arizona photographer Lori Bailey is tracking a lightning storm, she relies on sensors for her cameras: “‘Cause Lori’s brain is just too slow to say, ‘There’s the lightning!'” she said.

But there’s more to this profession than automated camera triggers and a lot of patience. You also need luck. She said, “You can do everything right and still not have the cards fall in your favor.

“I have to admit, I enjoy feeling that atmospheric energy when you get close to lightning. It’s kind of a natural high, you know, when the bolts are striking and they’re really close.”

When conditions do go her way, the results (which she posts online) are spectacular.

Beautiful and dangerous, lightning bolts are one of nature’s most captivating and misunderstood phenomena.

Beautiful and dangerous, lightning bolts are one of nature’s most captivating and misunderstood phenomena.

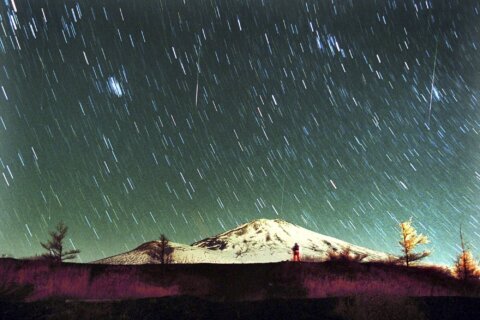

Lori Bailey

Inside a storm cloud, millions of tiny ice crystals collide with slushy hail-like droplets. The ice crystals blow upward with a positive charge; the slush droplets drift downward with a negative charge. Eventually, the charges equalize in a bolt of lightning. It usually stays inside the cloud, or hops from cloud to cloud. But the bolts that most interest people are the ones that shoot down to the ground.

Or seem to. Phillip Bitzer, a lightning physicist at the University of Alabama at Huntsville, said, “We talk about misconceptions – does lightning go up or down? And it starts with stuff that comes out of the cloud, but that stuff that comes out of the cloud, it’s so dim, you don’t make it out with your eye. The part that you see actually comes from the ground and goes up to the cloud.”

The lightning bolt is about the width of your thumb, as bright as a hundred million light bulbs, and five times as hot as the surface of the sun. “It will superheat the air right around it,” Bitzer said, “and eventually that superheat will cool off and relax into this acoustical wave that we all know as thunder. So, you can’t have thunder without the lightning.”

We asked Bitzer about some traditional lightning tropes. Like, “Lightning never strikes twice in the same place”? “So, it absolutely does,” he said. “And often what will happen is a single lightning flash, it can hit three to five times in the same place.”

Or, “Lightning always hits the tallest point”? “That’s another misnomer,” he said. “It doesn’t have to hit the tallest object. Lightning has already traveled a couple of miles from the cloud to the ground. At that point, it’s going to go where it wants to go.”

Or that lightning strikes are rare (almost as rare as winning the lottery)? “There’s a lot of lightning that happens,” Bitzer said. “Around 45 times every second around the world, you’ll get lightning.”

All told, that’s about 1.4 billion bolts hitting the Earth each year – numbers that are expected to rise as the planet warms. And about 250,000 times a year, lightning hits people.

In 2015, a sudden storm interrupted a school soccer game in North Carolina. Teacher Shana Turner sought shelter in the doorway of a shed. But when lightning struck a nearby light pole, millions of volts coursed through the ground and into her body. “I remember the sound,” she said. “It just sounded like it was a bomb going off. It was almost deafening. In my vision, [it] was slow motion.”

Like the vast majority of human lightning strikes, it was an indirect hit. Turner was thrown to the ground. “Within about a minute, my arm, it felt like it was boiling, in my arm. It eventually went to where my feet were tingling.”

Lightning strikes often lead to memory issues, heart problems, and even personality changes; after all, your brain and heart are electrical systems. Turner said that, within the first couple of weeks of class, she couldn’t remember some of her students’ names. “There was one instance where I went to call on a student’s name and I couldn’t come up with it,” she said. “So, I just turned to the board and, you know, tears rolling – I was trying to keep it away so my students couldn’t see it, trying to choke it back. And he came up to me and he hugged me and he said, ‘You can call me anything you want.'”

There wasn’t much doctors could do. “All I kept hearing was, ‘This is the strangest thing I’ve ever seen,’ or, ‘What you’re describing doesn’t make sense,'” she said.

Eventually, Turner found a group of lightning survivors on Facebook. “That’s when I started to figure out that I wasn’t alone,” she said. “I wasn’t the only one having these symptoms. I wasn’t crazy.”

The group gets together twice a year, and Turner has never missed a meeting.

CBS News

If you want to minimize your chances of getting hit by lightning, go indoors or stay in your car. Bitzer said, “‘When thunder roars, go indoors.’ There’s a reason why we say that.”

Still, the biggest threat isn’t lightning hitting people; it’s lightning starting fires. “Most forest fires are caused by humans, but most damage is done by lightning-caused wildfires,” Bitzer said. “Usually because, when lightning happens, it’s not near a campground where you know it happened; it happens in some remote location that you might not know that the fire started right away.”

We may no longer believe that Zeus hurls lightning down from Mount Olympus when he’s irritated. But there’s still a lot we don’t know. Bitzer said, “Everybody thinks, ‘Lightning, well, you must understand it, happens all the time!’ And yet, we don’t. The stuff that we see only lasts for, you know, maybe a millisecond.”

Our best hope is to build instruments. In fact, Bitzer himself helped developed a lightning camera that’s on the International Space Station at this moment.

Pogue asked, “Is there any practical value for mapping the lightning and how it happens? Or is it just kind of neat?”

“We know that [often] lightning will ramp up as a precursor to severe weather,” Bitzer said. “And so, we can watch the lightning activities start to increase or start to jump. We’ve also been able to use it to help aviation; we can route planes around storms that are electrically active.”

Back here on Earth, Shana Turner is still fighting to recover from her lightning strike eight years ago. “Obviously the brain damage will never get any better,” she said, “but I’ve learned how to do other things to assist with it. I’m not going to let it stop me. If I let it stop me, it wins.”

A tattoo Shana Turner got, holding a lightning bolt.

A tattoo Shana Turner got, holding a lightning bolt.

CBS News

And in Arizona, two days after our visit, photographer Lori Bailey got some of that good luck she’d been chasing: “Oh, my goodness! This is where you feel alive, where you feel the energy of Mother Nature!” she said.

Lori Bailey

For more info:

- Arizona photographer Lori Bailey

- Follow Lori Bailey on Instagram

- Phillip Bitzer, associate professor, Atmospheric and Earth Science, University of Alabama at Huntsville

- LS&ESSI (Lightning Strike & Electrical Shock Survivors International) on Facebook (private group)

- Lightning Safety Tips and Resources (National Weather Service)

Story produced by Robert Marston. Editor: Steven Tyler.