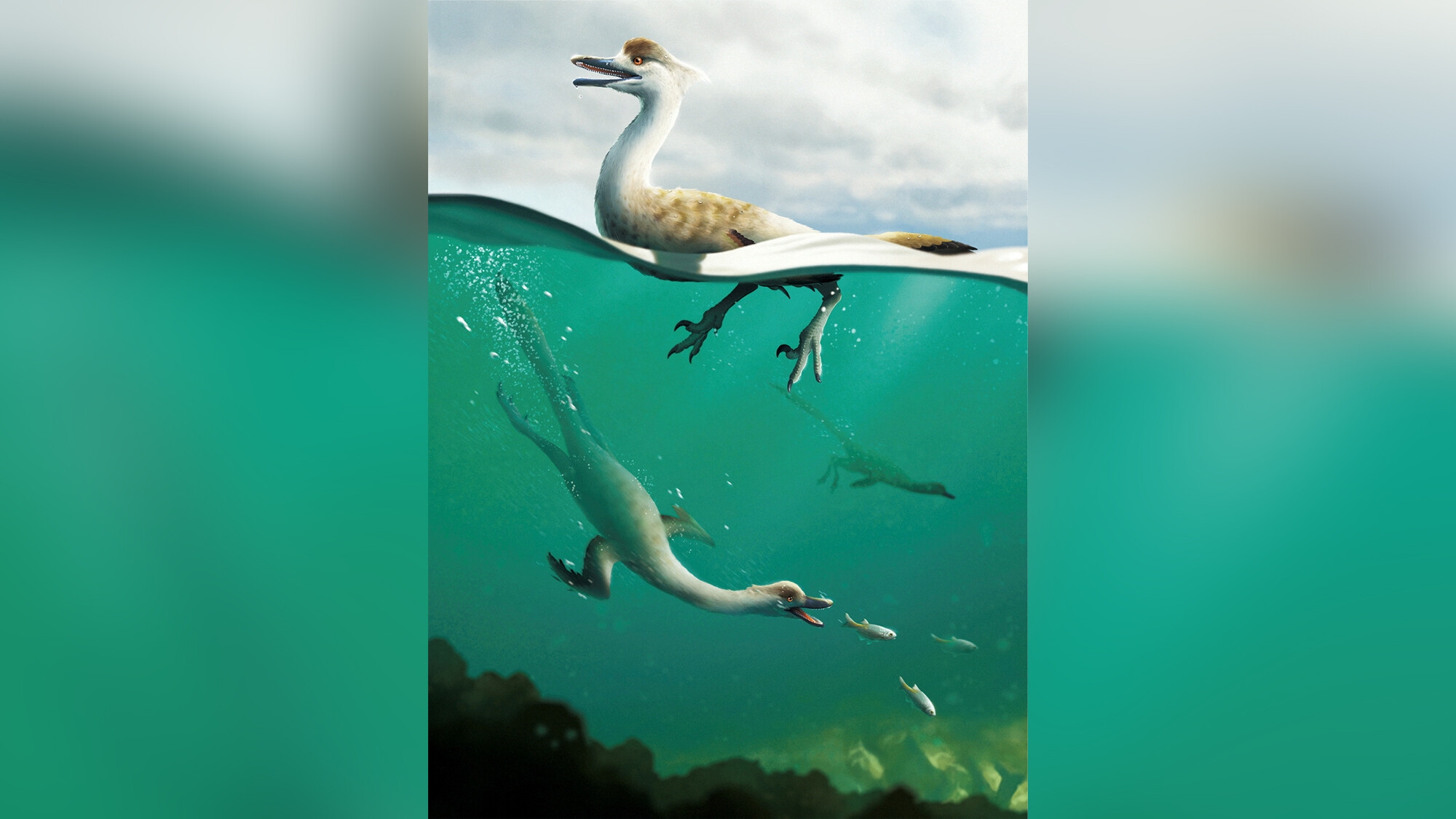

A new study found evidence at least one species of dinosaur may have been an adept swimmer, diving into the water like a duck to hunt its prey.

The study, published in Communications Biology on December 1, describes a newly-discovered species, Natovenator polydontus. The theropod, or hollow-bodied dinosaur with three toes and claws on each limb, lived in Mongolia during the Upper Cretaceous period, 145 to 66 million years ago.

Scientists from Seoul National University, the University of Alberta, and the Mongolian Academy of Sciences collaborated on the paper.

The researchers pointed out Natovenator had streamlined ribs, like the those of diving birds.

“Its body shape suggests that Natovenator was a potentially capable swimming predator, and the streamlined body evolved independently in separate lineages of theropod dinosaurs,” wrote the authors.

The Natovenator specimen is very similar to Halszkaraptor, another dinosaur discovered in Mongolia, which scientists believe was likely semiaquatic. But the Natovenator specimen is more complete than the Halszkaraptor, making it easier for scientists to see its streamlined body shape.

Both Natovenator and Halszkaraptor likely used their forearms to propel them through the water, the researchers explained.

David Hone, a paleontologist and professor at Queen Mary University of London, told CNN it is difficult to say exactly where Natovenator falls on the spectrum of totally land-dwelling to totally aquatic. But the specimen’s arms “look like they’d be quite good for moving water,” he said. Hone participated in the peer review for the Communications Biology study.

Additionally, Natovenator had dense bones, which are essential for animals diving below the water’s surface.

As the authors wrote, it had a “relatively hydrodynamic body.”

The next step, Hone said, would be to perform modeling of the dinosaur’s body shape to help scientists understand exactly how it might have moved. “Is it paddling with its feet, a bit of a doggy-paddle? How fast could it go?”

Further research should also look at the environment in which Natovenator lived. The specimen was discovered in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, but there is evidence there have been lakes and other bodies of water in the desert in the past.

“There is a real question of, OK, you’ve got a swimming dinosaur in the desert, what’s it swimming in?” he said. “Finding the fossil record of those lakes is gonna be tough, but sooner or later, we might well find one. And when we do, we might well find a lot more of these things.”

Nizar Ibrahim, a senior lecturer in paleontology at the University of Portsmouth, whose research has included findings indicating Spinosaurus was likely semiaquatic, told CNN he isn’t entirely convinced by the study’s findings yet. He argued more rigorous quantitative analysis would have made the findings more compelling.

“I would have liked to see, for example, a real solid description of the bone density, the osteohistology of the animal, within a larger data set,” he said. “Even the rib anatomy, if they had kind of put that into a larger picture — the big data set that would have been helpful.”

The “anatomical evidence is less straightforward” for a swimming Natovenator than it was for a swimming Spinosaurus, he said.

And like Hone, he’s also curious about which waters exactly Natovenator might have been swimming in. “The environment this animal was found in Mongolia, is kind of the exact opposite of what you would expect for a water-loving animal,” he said.

But he hopes the study can help open the door for more expansive ideas about dinosaur behavior. Dinosaurs were previously thought of as strictly terrestrial, but increasingly, evidence has emerged suggesting at least some species spent as much time in the water as they did on land.

“I’m sure that there will be many, many more surprises,” said Ibrahim. “And we’ll find out the dinosaurs were not just around for a very long time, but also, you know, really diverse and very good at invading new environment.”