WASHINGTON — Some of these beasts could give H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu a run for his money.

The National Museum of Natural History‘s new “Sea Monsters Unearthed: Life in Angola’s Ancient Seas” exhibit, opening Friday, introduces visitors to never-before-seen fossils of ferocious predators that populated the seas of the South Atlantic millions of years ago, during the Cretaceous period.

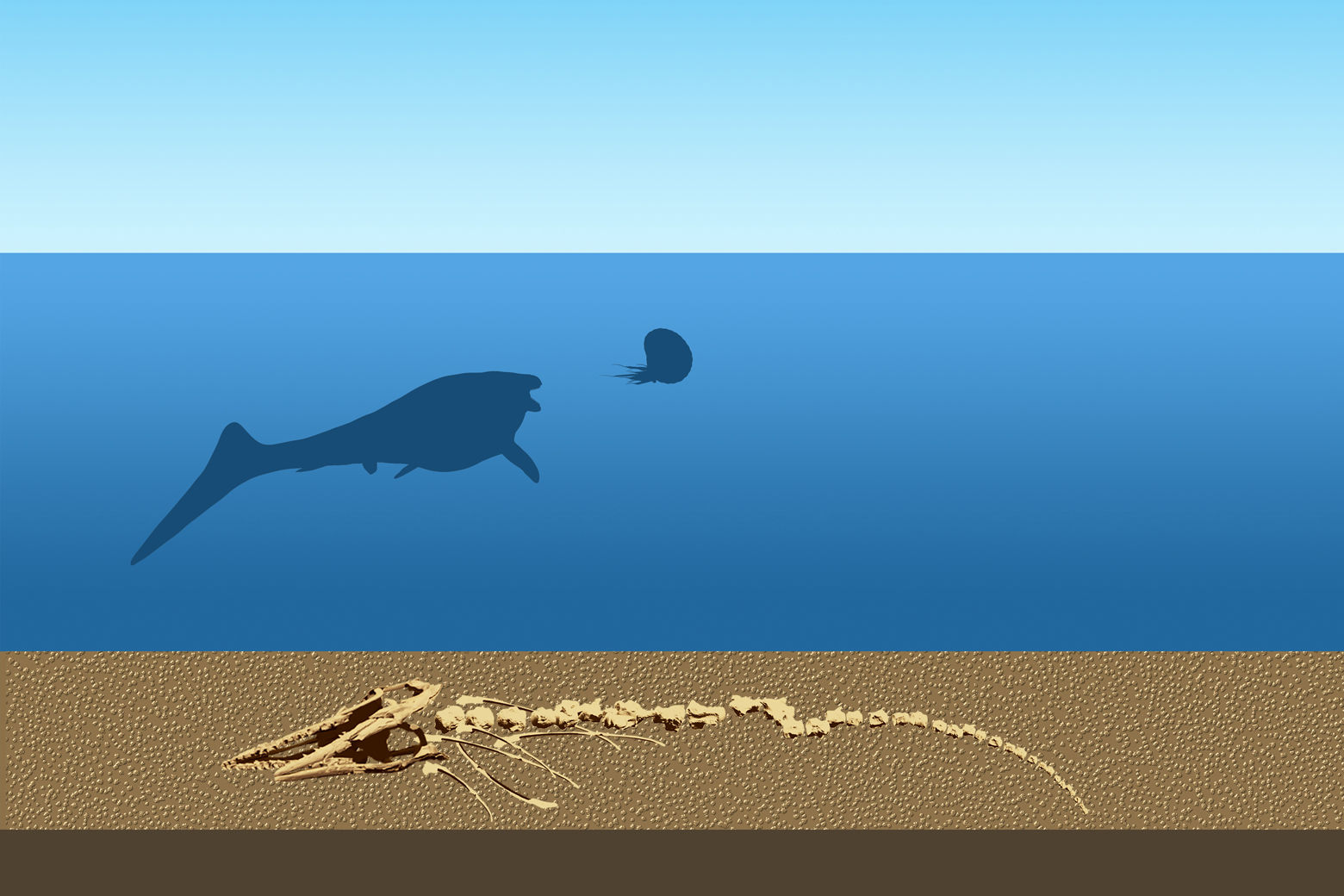

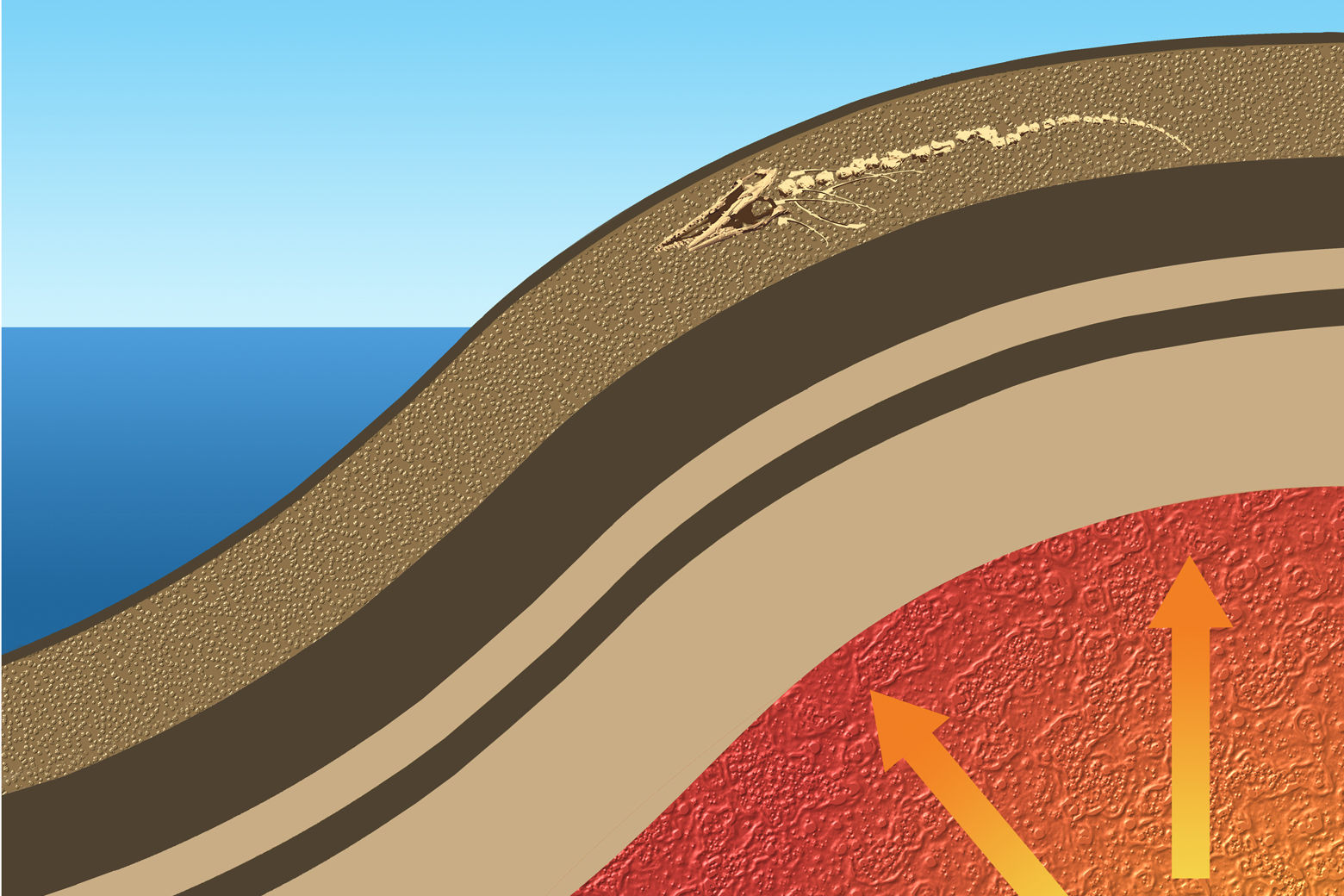

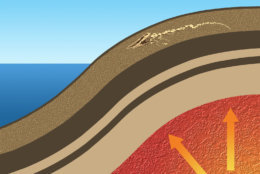

The exhibition focuses specifically on the marine reptiles that roamed the South Atlantic Ocean basin after it was formed when the African and South American continents drifted apart some 130 million years ago.

More than 130 million years ago, the South Atlantic simply didn’t exist. And new, terrifying life-forms soon colonized the area.

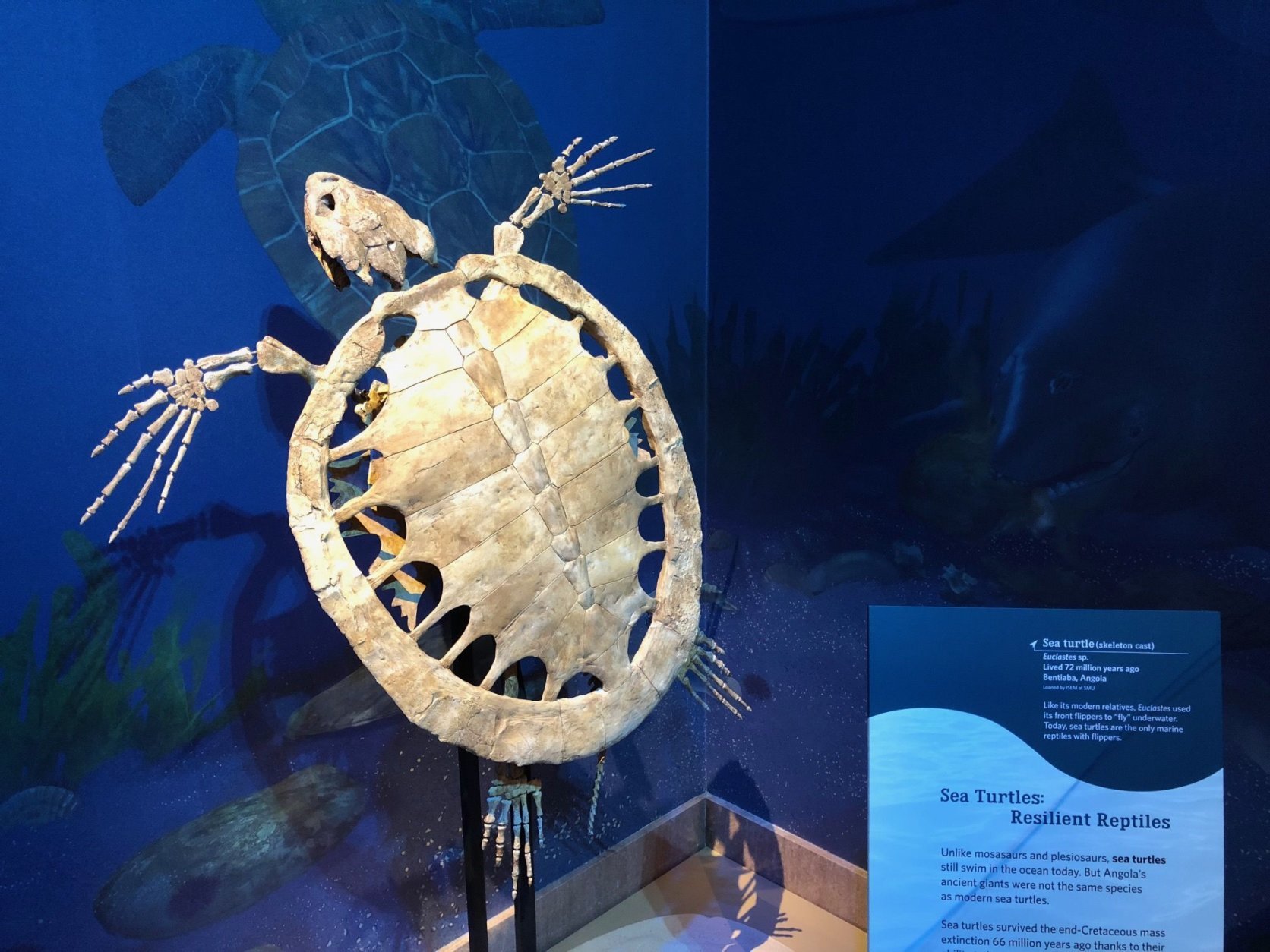

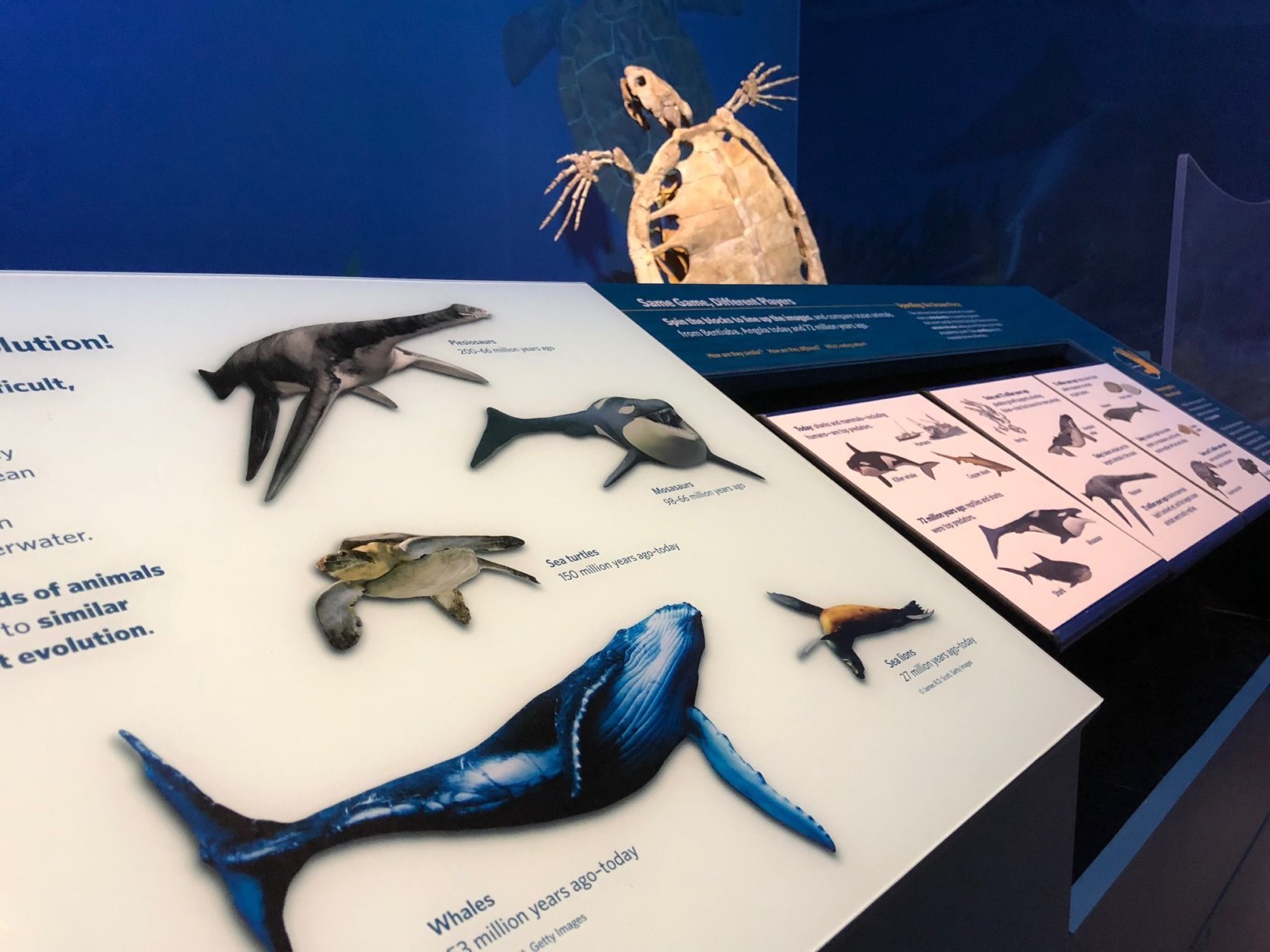

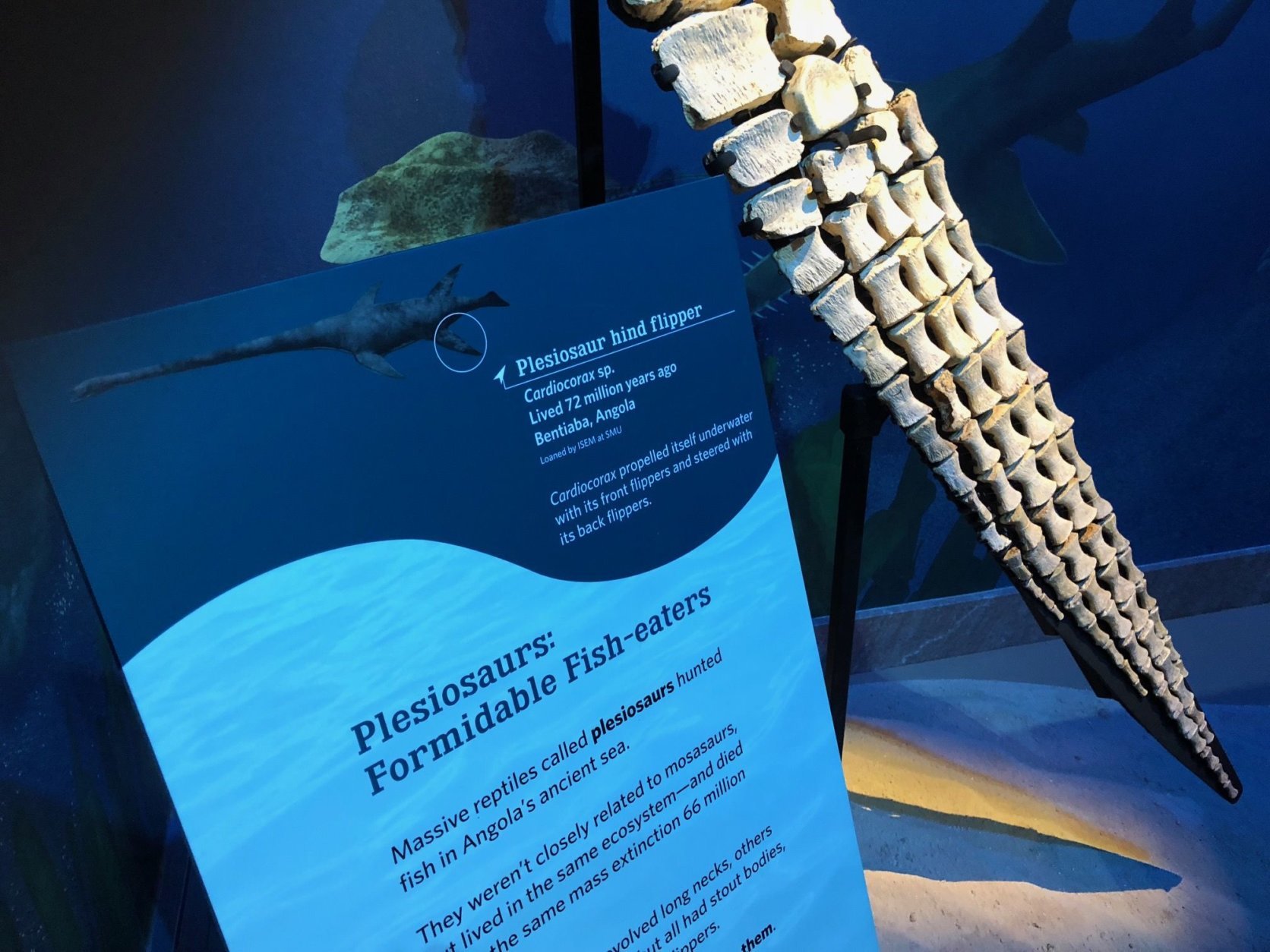

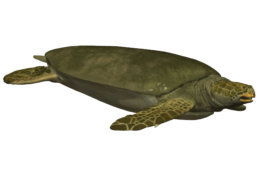

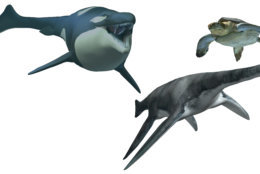

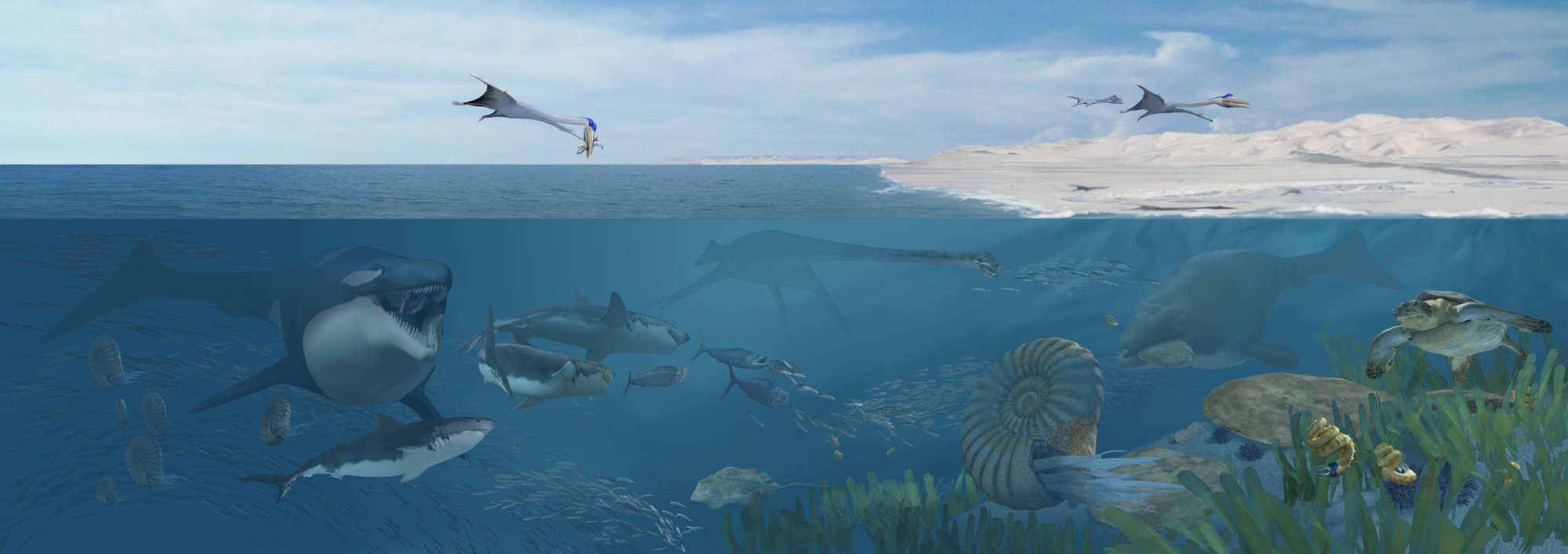

Among the monsters were long-necked plesiosaurs, mosasaurs and even enormous sea turtles.

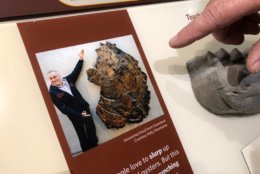

Louis Jacobs, professor emeritus of earth sciences at Southern Methodist University and collaborating curator for the exhibition, told WTOP’s Kristi King that the exhibit will have a major impact on those who experience it.

“It will spark their curiosity, it will answer their questions, it will start them in a pattern of thinking that will change the world,” Jacobs said.

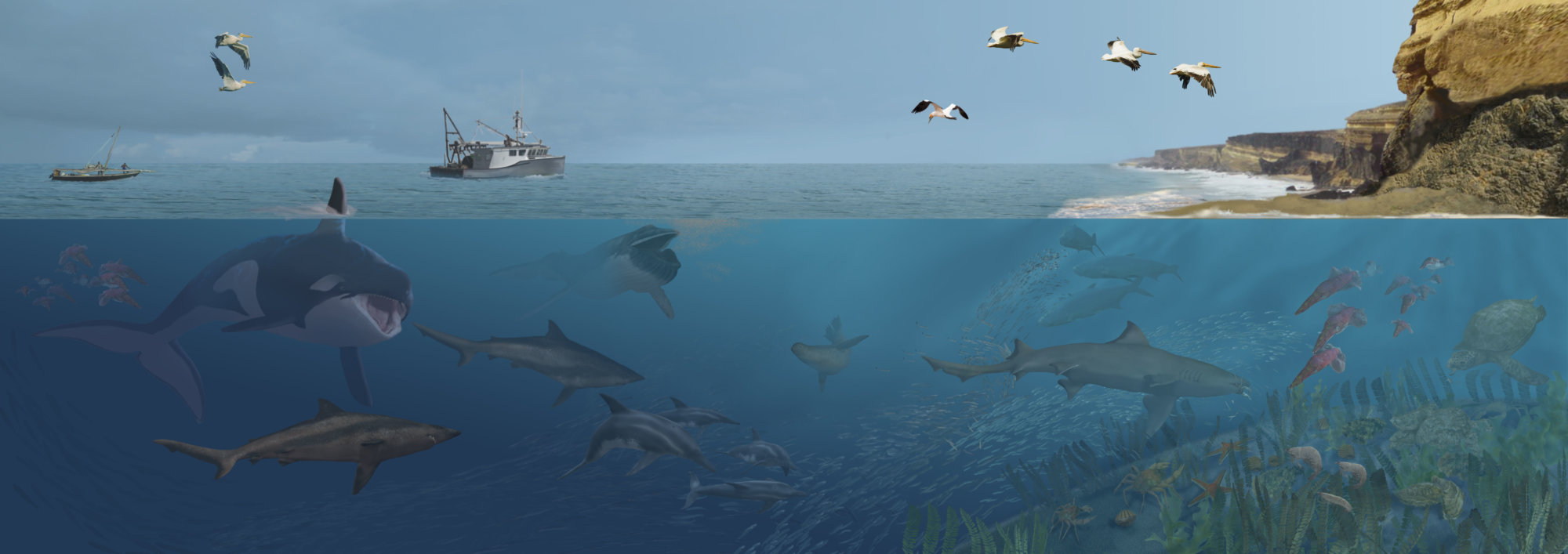

According to Jacobs, there is also a startling similarity between the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period and the state of the environment today.

“Only the sea turtles, as marine reptiles, made it through,” Jacobs said. “Now, a similar ecosystem, with different organisms in it, are a source of protein for people — it’s a very large fishery — but it’s in danger also of something that could turn out to be an equally big extinction.”

“The lesson to learn is that when the Earth does an experiment, we can learn from it, and we know that it takes millions of years to recover. Humans can learn from that because they don’t have millions of years to recover from something of the enormous magnitude of driving an ecosystem extinct,” he cautioned.

The exhibit is a cooperative effort between paleontologists and artists working together to determine what ancient animals and their environments looked like based on fossil evidence.

“Fossils tell us about the life that once lived on Earth, and how the environments that came before us evolve over time,” Jacobs said.

“Our planet has been running natural experiments on what shapes environments, and thereby life, for millions of years. If it weren’t for the fossil record, we wouldn’t understand what drives the story of life on our planet,” he explained.

Paleo-artist Karen Carr created multiple murals and reconstructions for the exhibit, which is part of the Projecto PaleoAngola project — a collaboration between Angolan, American, Portuguese and Dutch researchers.

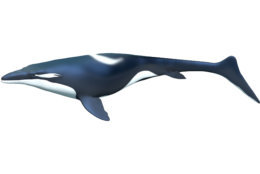

Visitors will notice that reconstructions of the mosasaurs bear a significant coloring resemblance to modern whales, despite the fact that whales are mammals and the creatures on display are lizards.

Senior research fellow at SMU Michael Polcyn explains that there’s a very good reason for that.

“I did some research with a colleague of mine in Sweden a few years ago … and we actually got pigment cells out of the skin of mosasaurs, and we were able to demonstrate that these animals are in the dark brown, gray to black sort of range,” Polcyn told WTOP.

“And when you start looking at marine animals generally — be they penguins or whales — you usually see this bicolor patterning where they’re light underneath, dark on top, so when we did the reconstructions with [Karen Carr], you can see from the murals … we chose to reconstruct them with whale-like patterns,” he said.

Yes. As if channeling Jurassic Park (though the likelihood of getting chomped by a dinosaur these days remains mercifully slim), Polcyn and his colleagues were able to extract pigment cells from fossilized mosasaur skin.

“It’s remarkable. We’ve been doing work with Johan Lindgren out of Lund University for a number of years now and we’ve been able to isolate a lot of biomolecules, actually, from mosasaur bones and now, in this case, skin,” Polcyn told WTOP.

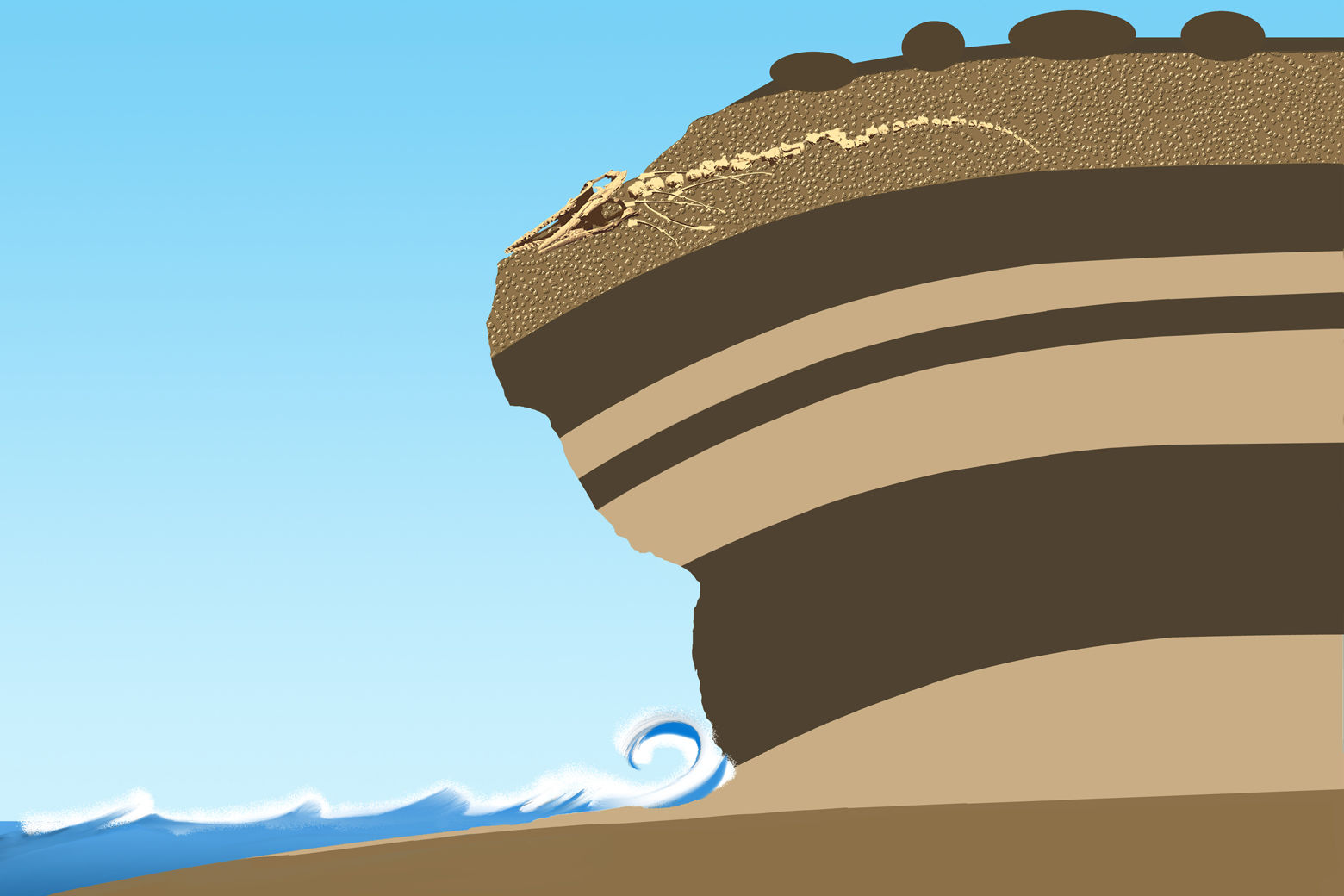

It is the first time that these Angolan fossils are on public display, and Polcyn emphasized that citizen or amateur scientists can be a great help to the field.

“An amateur today can make an incredibly valuable contribution just walking the creeks or the deserts, finding things, studying them, bringing them to the attention of scientists,” he said. “You can really make a great contribution as a citizen scientist.”

Some of the most striking fossils are of the mosasaur Angolasaurus bocagei, which was excavated from Angola’s coastal cliffs. The Angolasaurus bocagei grew up to 13 feet long and, with its curved teeth, likely hunted fish along the coast. It is the oldest-known mosasaur from the South Atlantic.

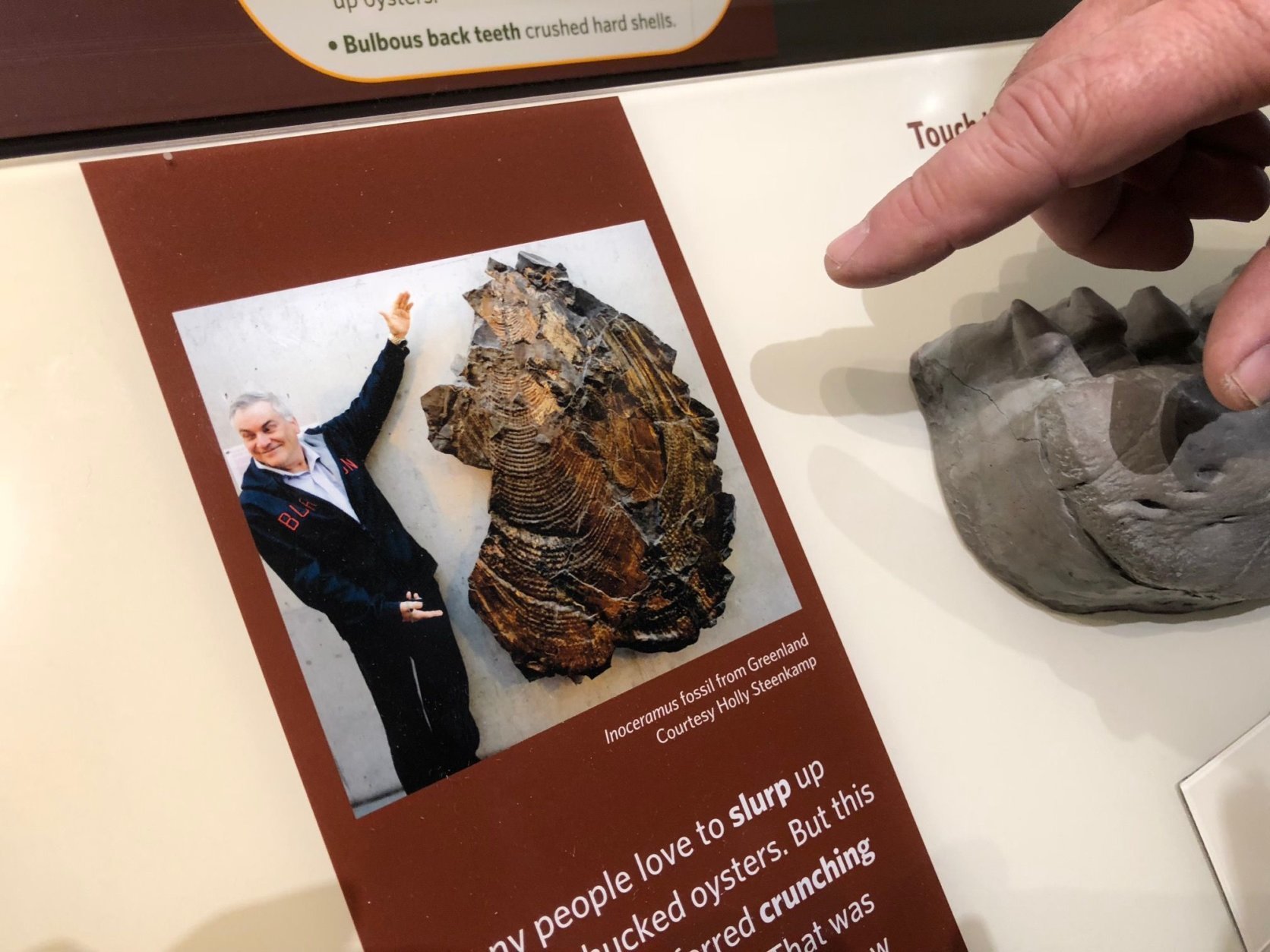

Another mosasaur depicted is the Globidens phosphaticus, which had teeth particularly well adapted to crunch through hard-shell treats such as oysters.

Scientists have determined that the shallow coastal shelf off Angola was once “a giant oyster buffet.”

A third type of mosasaur — the Prognathodon kianda, named for Kianda, the ruler of the ocean in Angolan mythology — is also highlighted in Carr’s artwork for the exhibit.

Sea turtles, of course, survived the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period (though scientists say humans currently threaten six of the world’s seven sea turtle species) some 66 million years ago. Fossils of one of their now-extinct ancestors, Angolachelys mbaxi, will be on display as well.

Here there be monsters:

“Sea Monsters Unearthed: Life in Angola’s Ancient Seas” is set to run until 2020.

The exhibit was made possible by the Sant Ocean Hall Endowment Fund

As H.P. Lovecraft’s fictional cultists say while they race to raise ancient alien monsters from the deep, “Ia! Ia! Cthulhu fhtagn!”

WTOP’s Kristi King contributed to this report.