(CNN) — President Joe Biden said before a critical trip to Europe that Ukraine is not yet ready to enter NATO. More to the point, the alliance is not yet ready for Ukraine to join in a historic step that could deter Moscow but that might also increase the risk of a US-Russia war.

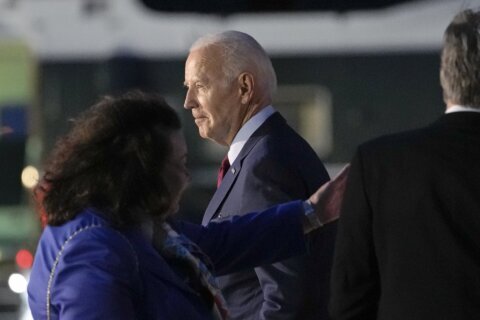

Biden has staked his foreign policy legacy on arming Ukraine to repel the Russian invasion – most recently with a contentious decision to send cluster bombs. But he nevertheless sent a strong message to Kyiv in an exclusive CNN interview that its increasingly sharp campaign is unlikely to result in a certain date for NATO entry emerging from the alliance’s summit in Lithuania this week.

While some eastern European alliance members are bullish on an early timetable to welcome Ukraine, some first-generation states, including the US, are more cautious, partly due to fears that moving quickly on NATO membership could provoke the direct conflict with Russia that Biden is desperate to avoid.

“I don’t think there is unanimity in NATO about whether or not to bring Ukraine into the NATO family now, at this moment, in the middle of a war,” Biden said in an interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria broadcast on Sunday. The president said that the alliance needed to lay out a “rational path” for Ukraine’s membership but that it was still short of some requirements for joining, including over democratization.

While Biden said he had discussed the issue at length with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and had refused before the war to allow Russian President Vladimir Putin a veto on Kyiv’s eventual membership, his comments will disappoint Ukraine as it suffers through a horrific war that has seen multiple crimes against humanity. Ukraine has often warned it is fighting the West’s war against Russian expansionism and has weakened NATO’s top adversary in Europe, and so therefore has a moral case for the defense guarantees NATO states enjoy. But even Zelensky accepts that Ukraine cannot join NATO while the war rages on.

Still, he hinted in an interview with ABC News aired Sunday that he wouldn’t be a guest at the NATO summit “for fun” and could stay away unless there was more clarity on membership and security guarantees. “It would be an important message to say that NATO is not afraid of Russia,” he said.

A fateful decision

Deciding whether Ukraine joins NATO is one of the most fateful European security questions since waves of expansion took the alliance right up to Russia’s borders in a process advocates say guaranteed post-Cold War peace by deterring Kremlin aggression. Critics of enlargement into formerly Soviet Eastern Europe, however, argue the process humiliated Moscow, turned it back into an avowed foe of the West and helped lead to the invasion of Ukraine.

A decision to admit Ukraine would extend the sacred NATO pledge that an attack on one member is an attack on all to a nation Russia regards, at a minimum, as part of its sphere of influence – even if such a claim has no basis in international law. It would commit future Western leaders to go to war with nuclear-armed Russia and potentially risk a third World War if the Kremlin attacked its neighbor again.

Supporters of Ukraine’s membership in NATO, however, argue that decades of security and territorial integrity provided to ex-Warsaw Pact nations like Poland, Hungary and Romania are in itself proof that once under NATO’s mutual defense umbrella, Ukraine would at last be safe from future incursions by Moscow. The argument is especially resonant since summit host Lithuania, like its fellow Baltic states Latvia and Estonia, was once annexed by the Soviet Union and considered highly vulnerable to Russia before its entry into NATO in 2004.

The case for Ukraine in NATO

Broadly, the case for NATO welcoming Ukraine includes those ironclad security guarantees that would be designed to dispel its vulnerability to Russian attack. Supporters of Kyiv’s accession point out that a vague promise of future membership – first made at its summit in Bucharest in 2008 with no realistic timetable for entry – offered Putin an incentive to invade before Ukraine joined the club.

NATO membership would also boost Ukraine’s bid to cement a democracy that was vulnerable before the war and fulfill the desire of many of its people to join the West. With its brutal war, Moscow has forfeited any moral say in whether Ukraine should join or not. And the addition of Europe’s most battle-hardened army, with more personnel under arms than most member states, would stiffen NATO’s military punch.

Sens. Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican, and Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat, last week introduced a resolution calling for a roadmap to Ukraine’s NATO membership as soon as it is practicable. “It is only through NATO membership that Ukraine can experience true security in the face of repeated Russian aggression,” the senators said in a statement. “Their fight has been a stand against corrupt crony authoritarianism and they have earned a secure and lasting peace within NATO.”

The case against

There are short- and long-term arguments against NATO offering membership to Ukraine. Biden warned in his CNN interview that to do so in a time of war would immediately commit the alliance to defend a new partner – to prove the group’s collective defense is meaningful. “I mean what I say,” the president said. “It’s a commitment that we’ve all made no matter what. If the war is going on, then we’re all in war. We’re at war with Russia, if that were the case.”

Offering Ukraine a set date to join after the war ends might be counterproductive since it would give the Kremlin a rationale for never ending the conflict. This would dash admittedly thin hopes for a political settlement if Ukraine’s forces are ultimately unable to expel all Russian forces. And it would risk strengthening Putin at home by appearing to justify one of his rationales for the unprovoked invasion – his baseless allegation that the West triggered the war to claim Ukraine in a bid to weaken Russian power.

As he headed to the United Kingdom on the first leg of his European visit, Biden got an endorsement of his strategy from GOP Rep. Michael McCaul, the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, who said it was “way too premature” to talk about Ukraine immediately joining NATO. “First they have to win the counteroffensive, secondly, have a cease-fire, and then negotiate a peace settlement. We cannot admit Ukraine into NATO immediately. That would put us at war with Russia,” the Texas Republican said on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday.

“So I think what the conversation is going to be about is, what security agreements can be put in place with Ukraine as a predicate to perhaps ascension of Ukraine into NATO?” he said, adding, “We have to be careful in the way we do this.”

US and European security guarantees to Ukraine – beyond the multi-billion dollar effort to arm the country to fend off Russia’s threat – would change the strategic picture in Western Europe. They would also be made with no guarantee that the Kremlin would become more benign toward the West in future decades. But there is no reason, for example, why the US and its allies cannot make a commitment to offer Ukraine the means to defend itself – short of NATO membership – much as the US does with Israel and Taiwan.

The risk of a clash with Russia in the future weighs heavily on the minds of many analysts. “The United States should not guarantee Ukrainian security. Period,” said Ben Friedman, policy director at Defense Priorities, a think tank dedicated to promoting a realist vision of national security policy. “We shouldn’t do so now, via NATO or otherwise (through) some sort of bilateral security guarantees, and we shouldn’t do so as part of a peace deal.”

Friedman argued that despite Ukraine’s heroic resistance, wider considerations of Washington’s interests must take priority. “Guaranteeing Ukraine’s security would erode US security by increasingly the risk, obviously, of war with Russia,” he said. “That contains the risk, of course, of nuclear escalation, and for that risk I think the United States receives basically nothing of security value.”

Neither Biden, nor any other member of his administration have made a case to the American people as to why ultimately it would be in the interest of 330 million Americans to go to war with Moscow to defend Ukraine if it joined NATO. In fact, the president has made an opposite, implicit case, stressing that despite a proxy-war type situation in Ukraine, his core concern is avoiding a direct clash with Russia. Advocates of NATO welcoming Ukraine often argue that no such undertaking was secured from American voters regarding other formally communist Eastern European states once in the Soviet Union’s orbit. But Ukraine could be more at risk since it carries greater cultural and historical associations – and, for Russia, it is linked to its self-identity, whether justified or not.

One potential downfall of offering Ukraine eventual security guarantees through NATO or another mechanism would be if political will to enforce them ebbs in future. A failure to defend such guarantees would raise grave doubts about NATO’s existing mutual defense ethos and could end up disastrously weakening the integrity of the alliance.

Even if Biden were to amend his position on accelerating NATO membership for Ukraine, he cannot ensure a successor would honor treaty obligations. Indeed, ex-President Donald Trump has been loudly warning that Biden is leading the US into a potential World War III against Russia, and he has insisted he’d end the war in Ukraine within 24 hours if elected to a new term. Such comments suggest more sympathy to the goals of Putin, to whom he has often cozied up.

The uncertain political situation in the US may be one reason why Zelensky has appeared so desperate to ensure his country’s urgent NATO aspirations are set in stone at this week’s summit.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.