The search for affordable, convenient, quality child care is a struggle in the Washington region. The five-part series Child Care Crisis will look at why it’s so hard to find care, and why costs are surpassing college tuition rates. The reports also examine the emotional toll the lack of child care takes on families.

WASHINGTON — D.C. resident Jennifer Kauffman didn’t even have a name picked out for her daughter and, already, her unborn baby was on a waiting list at several day care centers.

Kauffman and her husband started their child care search at a time when most expectant parents are just getting around to telling family and friends the good news, but they felt like they were behind schedule. Even with six months of her pregnancy left, plus time off for maternity leave, nearly every center was full at the time Kauffman was expecting to return to work.

“We were already on waiting lists for this child that was, you know, the size of a bean,” said Kauffman, who felt discouraged knowing there were several families on the list ahead of them.

To make matters more frustrating, Kauffman, who works at a digital creative agency, paid several nonrefundable deposits of hundreds of dollars just to put her name on those lists — including some places she never heard back from about an opening.

“At 100 bucks a pop, that’s not easy for us to pay out of pocket,” she said.

The second report in the Child Care Crisis series explores the many factors contributing to a child care shortage in the D.C. area, including a growing infant and toddler population and the realities of running a day care.

No care to spare: When supply outgrows demand

In 2015, there were roughly 7,610 slots at licensed care providers for 22,000 children under the age of 3 in D.C., according to a report published by DC Appleseed, a policy-focused nonprofit. This means there is enough room for roughly one-third of D.C.’s current batch of infants and toddlers — a population that is increasing in size.

The Washington Post reports infants and toddlers are the fastest-growing age group in the city, with 26,500 children younger than 3 in 2013 — a 26 percent increase from 2010. Areas surrounding the city are also welcoming more babies as the millennials who flooded the region after the recession venture into parenthood.

In Arlington, Virginia, Erika Gibson, child care supervisor for the Arlington County Department of Human Services, said most of the county’s 50 licensed care centers have waiting lists for children under 2.

Liz Kelley, acting assistant state superintendent for the Division of Early Childhood Development at the Maryland State Department of Education, said finding a space in a day care, especially in the counties hugging the District, “is a very difficult thing, especially for [parents of] infants and toddlers.”

“Parents will very often, as soon as they know they’re pregnant, … put their name on a waitlist so that they can have access to those slots,” she said.

In extreme cases, the child care shortage forces some parents to put their children in unlicensed care or to leave the workforce. Both choices can have long-term consequences.

Unlicensed care providers don’t have oversight, meaning caregivers may not be trained in basic techniques such as first aid and CPR.

The Center for American Progress said that while one parent’s salary may rival the annual cost of child care, the economic implications of staying home — losses in future wage growth and in retirement savings — last for decades.

There is no reported shortage of private nannies in the area, but the higher cost of nanny care (between $37,000 and $41,600 a year, based on a 40-hour workweek) prohibits many families from exploring the option.

The cost of doing business

Amy Ginn and Brian Stanton, of Kensington, Maryland, also thought they were being proactive in their search for child care.

“I hadn’t looked until I was six months pregnant. And so by then, it was way too late,” Ginn said. “It seemed like you had to get on a waitlist about — I don’t know, at least nine months ahead of time.”

The couple, both lawyers, lucked out and found a new child care center that was opening in the area. They went to an open house and signed up on the spot. The center opened one week before Ginn went back to work.

“It was pure luck,” she said. “It might not be the fanciest day care center, but the people are very warm and there’s not a huge staff turnover, which is usually a good sign.”

It’s more than that — it’s a rarity in an industry troubled with a limited supply of caregivers who often leave to find higher-paying work.

Shana Bartley, acting executive director for DC Action for Children, said a small and often underpaid workforce is another reason why there’s a shortage of care options.

“We find that compensation for the field, as well as what we’re learning through brain science — what are the qualifications that we would need for high-quality early care and education — we just don’t have that many teachers,” Bartley said.

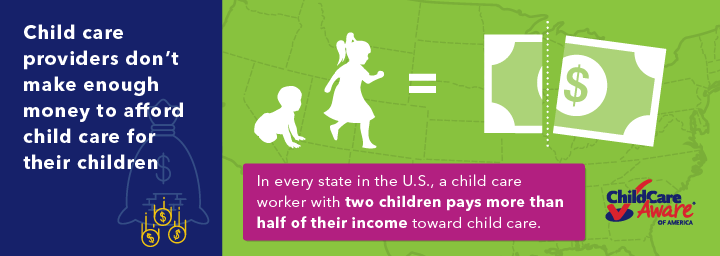

Despite the high cost parents pay for child care (tuition for center-based care for infants averages $1,868 a month in D.C., or $22,416 a year), DC Appleseed reports those who care for children earn wages slightly higher than fast-food cooks; many aren’t offered health insurance or retirement benefits.

That said, business owners are not taking home big paychecks.

“I talked to a parent who said, ‘You know, these caregivers, they charge so much money they must be flying around on their own private planes,’” said Brigid Schulte, director of Better Life Lab and The Good Life Initiative at the D.C.-based think tank New America.

“I think what people don’t realize is that it takes a lot of bodies to be able to provide child care and early care and learning,” Schulte said, adding that centers have strict adult-child ratios, especially for infants and toddlers.

The region’s high rents and strict zoning rules also make it tough for centers to open and stay operational.

Day care centers in areas that serve mostly low-income families have even more of a disadvantage, since subsidy rates fall well below what it costs to provide care. In D.C., reimbursement rates range from 55 percent to 74 percent of market value, making it difficult for centers to stay in business.

A report by Child Care Aware of America says that at many large centers, providers offer infant and toddler tuition at a price below what it actually costs to care for the children. They’re able to do this by averaging expenses across all ages and supplementing parent fees with money from a range of public and private sources.

“It is hard for small business with just infants and toddlers to break even, but when they bring in pre-K-aged children or they have some of our pre-K enhancement funding (they can make some money),” said Elizabeth Groginsky, assistant superintendent of early learning for the District of Columbia Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

In DC Appleseed’s report, a few providers admitted they went into personal debt to float their centers.

Kristin Schubert, managing director of the Healthy Children Portfolio at Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which works on public health issues, said families farther away from the region’s urban centers don’t have it any easier — they often have even fewer options than those in more densely populated areas.

“In too many towns around the country, people just don’t have the choice … and that’s not OK. We call those child-care deserts,” Schubert said.

“By and large, the majority of parents in this country need to work. So having good, safe environments to take their kids every day is super-important,” she added.

Making more room

The good news is that local jurisdictions are aware of the problem and are working to address it.

Arlington County is in the process of launching a countywide effort to explore ways to increase access to care, such as incentive options for business owners and a re-examination of zoning regulations.

Maryland offers low-interest loan programs through the Department of Commerce for business owners wanting to open a child-care center and grant programs to help finance equipment, materials and training. Some centers are even rethinking their classroom structure.

“We’ve found over the last several years that most facilities that have historically only provided care for preschoolers and up are now looking at expanding those to infant and toddler slots because there is such great demand,” said Kelley, with the Maryland State Department of Education.

D.C.’s Groginsky said the District is working on strategies with private partners to address availability. A $10 million investment from the Bainum Family Foundation aims to increase the number of infant and toddler slots by at least 750, especially in neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River.

In January, at-large Councilmember David Grosso submitted legislation to eliminate facility costs for early learning providers in D.C. by arranging space for child-care centers to expand in District-owned or District-leased buildings.

If DC is to become a world-class city for #education, we must plan ahead and invest more money in children 0-3 y/o. https://t.co/KsIL932H6U

— David Grosso (@cmdgrosso) January 24, 2017

“My staff and I figured that if we had access to construction sites, we would put one of these (centers) in every single spot,” said Grosso, who added that paying for and building out space is one of the biggest barriers child care business owners face when it comes to expanding.

The goal of his legislation is to pass the savings down to the families.

“The number of children in our city has grown tremendously and the average cost is something around $22,000 a year, so we’re doing everything we can on every angle,” he said.

The third report in the Child Care Crisis series will explores the high cost of child care in the D.C. area.