WASHINGTON — “I wish you’d have come yesterday.”

The end of the day on a Friday is a tough time to judge any operation. It’s as true in any corporate office as it is in a math class at Ballou High School, one of the city’s most trying learning environments. That’s where a 26-year-old from Baltimore is trying his best to teach both basic math and basic life skills, learning on the fly himself in his second career.

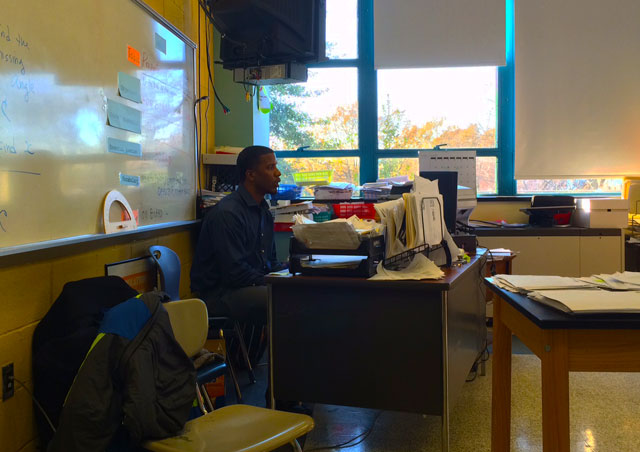

Ricardo Silva may look the part of your normal Teach for America participant. Many young men and women end up in the program after trying their hand at one career or another first. But not many come from the NFL.

After playing two years each at Bowie State and Hampton, Silva went undrafted despite a huge senior season. He graduated and signed with the Detroit Lions’ practice squad, and when he suffered an injury late in camp, he wasn’t cut, but rather assigned to injured reserve thanks to his attitude. The safety shone at times in 2012, making six starts, but he was cut after the season. He was signed by the Carolina Panthers in August 2013 but waived three weeks later.

He had an offer to go to the University of Hawaii to be a coach. His agent tried to push him to take an offer in the Canadian Football League. But teaching was always the plan, and doing it here in D.C., where he knew he could make an impact.

“I always wanted to teach,” he explains, saying that it was only a matter of when he stepped into the classroom after football. “I did what I wanted to do. The NFL is really enticing, but this is where I wanted to be.”

It can be hard for some to imagine giving up the glitz and glamor of a professional athlete’s lifestyle for the rigors of teaching — not to mention trading in over $400,000 in minimum salary for $51,000 a year. Surely, in order to feel justified, there must be days more like the one depicted in the People Magazine profile, the shiny profile photo of teacher and three students smiling under perfect lighting.

But this is not one of them.

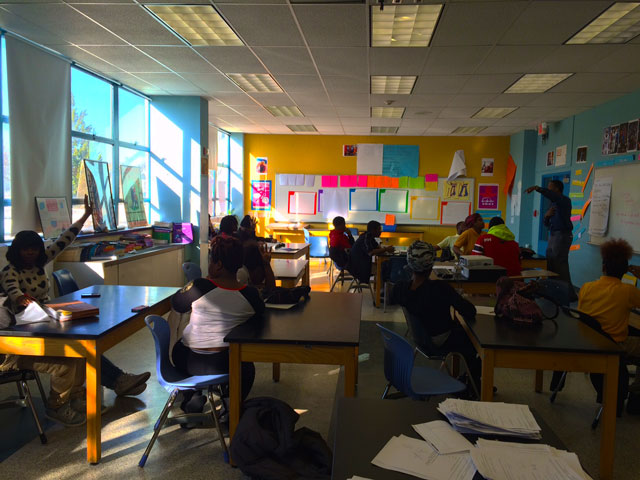

Silva has been running around like a madman this afternoon to and from parent-teacher conferences. While he’s gone, his room devolves into chaos. When Silva returns momentarily, the hum of conversation continues, but at a suppressed level, the profanity gone. He leaves again, and a heavy, hard cover book flies from a student’s hand and hits the floor just seconds later, but within his earshot in the hallway.

“Look, if y’all can’t get it right…” he says as he pops his head back in the door.

During Silva’s absence, his co-teacher, Mrs. Jacobson, tries her best to corral a group of 12 to 15 heavily distracted students. For those who graduated before, say, 2005, it’s hard to imagine the challenges that cellphones present in high school. The constant access to friends and the web are a ubiquitous distraction in a world where an already precarious social status is now measured tangibly through followers and likes.

It’s not Jacobson’s fault. A tiny Cuban woman with cropped magenta hair and fully grown children, she does her best to keep up in an environment where she is clearly the outsider. But with her thick accent, foreign upbringing and more than a generation of age gap between her and the students, she’s fighting a different battle.

That’s why it’s important for a place like Ballou to have a teacher like Silva.

“He has good values,” says Jacobson. “They are lucky to get him. A teacher that cares, someone who is committed to seeing these kids succeed.”

Silva returns from his final conference to take control of the class. In his solid indigo dress shirt and graphite-colored slacks, his slightly raspy natural timbre fights the din of a room full of young voices. When they are not as responsive as he would like, Silva’s inflection suddenly ratchets up a notch, into the kind of bark that needs to be heard over a crowd of thousands of screaming fans; not aggressive, but sharp and pointed enough that it generates a quick change in behavior, the students finally sitting in their desks, facing forward.

If you’ve never seen an environment like it, you might be surprised to realize one of the biggest issues teachers like Silva face. In addition to fighting the uphill battle against truancy, they often face the problem of over-attendance — unwelcome visitors, students from other classrooms, who wander in for whatever reason, causing additional distraction.

“I’ll see you later,” Silva says to these intruders, a gentle technique to guide them back out in the direction they are supposed to be.

He gathers enough attention to play a mental game with the students, in which they are to take a number, add, subtract, multiply and divide by four other numbers, then show the final result on their fingers. As one student calls out the numbers, a room of brains crunching the arithmetic translates into a backdrop of silence. It’s the first time the room has had only one voice in an hour.

Even as a rookie in the classroom, Silva has made big strides in certain areas in his first semester on the job. In an early confrontation, he was cursed out by one of his students and felt like he lost command of his classroom. The past few months have been measured in incremental progress.

“When I first got here, it was traumatizing,” he says.

It’s a funny thing to hear from the mouth of a 6-foot 3-inch, 200-plus pound man who used to spend his Sundays smashing heads with some of the largest and fastest athletes on the planet. Silva’s best career game came in a 28-24 win over the Seattle Seahawks in 2012, in which he picked off Russell Wilson and recovered a fumble on the game’s final play to seal the win. Two of his tackles in that game were of Marshawn Lynch, maybe the most brutalizing downhill runner in football, who punishes defensive players who get in his way.

So, what’s tougher: a day on the gridiron, or one in the classroom? He answers definitively and without hesitation.

“This. This, this, this, this,” he says. “Not necessarily teaching, but the whole package.”

Silva teaches math, and wants to impart its importance to his students. “THE ROAD TO SUCCESS IS PAVED WITH DATA” reads a block printout, one letter per vertical, 8½ x 11 sheet, across the back of the room. It’s Silva’s message, and yet he serves as a life coach as much as he does a math teacher most days.

“A lot of these kids are the head of their households at 13, 14,” he explains. “You can’t just force it on them. We’re trying to build a community here.”

He believes his stature as a young black man is more important in his ability to relate to his students than the fact that he played professional football. Jacobson agrees.

“Of course, the NFL thing doesn’t hurt,” Silva admits with a smile. “It makes me automatically cool.”

But despite his background, he hasn’t started coaching with the football team yet. He’s still getting adjusted to his new work environment, and finishing his credential during the evenings. However, he’s taken the little spare time he does have to start an after-school math club. It functions as a study hall for those motivated to make up for some of the time lost during the hectic school day.

“It’s definitely more important than football right now, for me,” he says.

Silva lives in Northeast D.C. with his wife, who is originally from Prince George’s County. The two met in college, and she is now a doctoral student at the University of Maryland. It’s a pretty normal life, considering the one he left behind to be here. But he doesn’t miss it, or regret it for a moment.

“I love it,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine being any other place.”