Caring for seniors with cognitive impairments who are living in nursing homes can be a challenging endeavor. One particular area of concern is the use of antipsychotic medications in treating older adults with dementia when associated behaviors become difficult to manage.

Sometimes called “chemical straightjackets,” antipsychotic drugs are usually used to treat certain mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Overuse or abuse of these medications in seniors without these conditions is what raises a red flag.

The percentage of nursing home patients who receive antipsychotic drugs is one of the measurements U.S. News uses in its ratings for Best Nursing Homes. For the 2023-2024 rating year, U.S. News’s findings comported with those of a 2021 New York Times investigation that revealed at least 21% of nursing home residents, more than 225,000 people in total, were on antipsychotic drugs.

U.S. News data found that at 22% of evaluated nursing homes, at least 1 in 4 residents received antipsychotic drugs. That number suggests excessive use of the medications.

While the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gave 678 of those homes a positive (four- or five-star) rating, none of them received a positive rating from U.S. News.

“(The New York Times) investigation was our inspiration for much of our work around antipsychotics,” says Ben Harder, managing editor and chief of health analysis at U.S. News.

Risks of Antipsychotic Use in Nursing Homes

Antipsychotic medications — as well as mood stabilizers and antidepressants — are just one piece of the treatment pie, alongside “lifestyle choices and social support,” says Stephanie G. Thompson, behavioral health director for Gary and Mary West PACE, a nonprofit providing medical and support service to seniors with chronic care needs. But this particular medication piece may not be the right choice for nursing home residents.

For instance, sedative antipsychotic medications, such as Haldol (Haloperidol), can be dangerous for older people. The FDA warns that giving Haldol to elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis significantly increases the risk of death from heart problems, falls and infections. That increased risk of death was calculated at 1.6 to 1.7 times greater, based on an analysis of 17 placebo-controlled trials.

“Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group,” the FDA warning notes.

For this reason, “Haldol injection is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis,” the FDA warning continues. Rather, it is intended to treat schizophrenia.

The Times investigation found that some nursing homes are adding a diagnosis of schizophrenia to a patient’s chart in order to get around this restriction. This means the use of the medication doesn’t have to be reported to Medicare and thus improves the standing of the facility in various agency records and rankings.

According to the investigation, 1 in 9 people in nursing homes have received a schizophrenia diagnosis. In contrast, in the general population, the condition affects about 1 in 150 people, and it’s almost always diagnosed prior to age 40.

Certainly, the trend of overmedicating or inappropriately administering powerful antipsychotics to nursing home residents to keep them calm is concerning. But preserving the accessibility of these medications for those who truly need them is also a consideration.

This all adds up to making the use of antipsychotics in nursing homes a “complicated, nuanced issue,” says Dr. Katherine Brownlowe, a neuropsychiatrist and clinical associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral health with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

[See: 8 Early Signs of Dementia.]

Why Antipsychotics Are Sometimes Used in Long-Term Care Settings

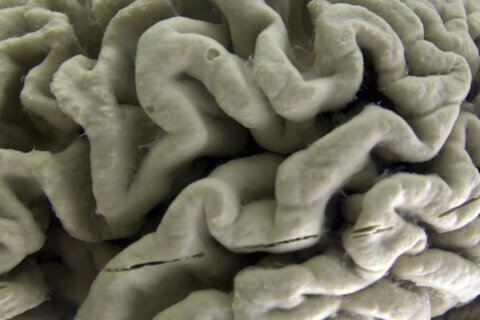

For older Americans who develop dementia, whether that’s Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia, a variety of symptoms can develop. No matter which type of dementia your loved one might be dealing with, memory will be affected. But memory loss is not the only issue these neurodegenerative conditions can create.

“I think we commonly think of older folks as having memory impairment; that’s often their primary symptom,” Brownlowe says. “But we also see changes in people’s ability to control their impulses and their ability to make good decisions as they get older.”

Those impulsive behaviors may be heightened in certain kinds of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia, adds Lisa Skinner, a Napa, California-based behavioral expert in the field of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“You may see aggressive behavior more often than not with frontotemporal dementia because the part of that brain that’s damaged is where we house our emotions, personality and judgment. People with that dementia are sometimes very sexually interested, or they’ll hit people or be prone to extreme outbursts of anger.”

While these behaviors might be more common with frontotemporal dementia, “you can see it with any type of dementia,” Skinner adds.

[READ: Must-Ask Questions When You’re Choosing a Nursing Home.]

Memory Loss and Psychiatric Symptoms

Behavioral issues, along with memory loss, confusion and an overall loss of ability to care for oneself, get worse over time and can lead to psychiatric symptoms. These symptoms can include:

— Delusions, a fixed, false belief.

— Hallucinations, a sensory perception that’s misaligned with reality, or seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling or tasting something that isn’t actually there.

— Paranoia, a state of extreme distrust of others and a feeling of being persecuted.

These symptoms can lead to angry outbursts or other behaviors that are hard to manage. In some cases, people with advanced dementia may develop symptoms similar to those seen in schizophrenia. A subsequent diagnosis of that condition then results in a prescription of the powerful antipsychotic medications.

Yet, “there’s no FDA-approved medication to treat these (psychiatric) symptoms” when they’re caused by dementia, says Elizabeth Galik, professor and chair of the department of organizational systems and adult health at the University of Maryland School of Nursing in Baltimore.

These symptoms cause distress for the patient as well as the caregivers and can greatly decrease the patient’s quality of life. The COVID-19 pandemic also exacerbated this situation due to understaffed or overwhelmed nursing homes. Caring for an agitated or noncompliant patient becomes very difficult when staff is already overburdened. A review published in the journal Neurology and Therapy suggests there’s a relationship between low staffing levels and an increased reliance on antipsychotic medications, though the study also notes more research is needed.

Medications like Seroquel (quetiapine), Zyprexa (olanzapine) and Abilify (aripiprazole) aren’t approved for use to address dementia-induced difficult behaviors, such as combativeness from a patient exhibiting intractable behaviors or experiencing delusions, hallucinations or paranoia, but they are sometimes prescribed off-label.

[READ: Nursing Homes vs. Assisted Living.]

Regulatory Efforts

Recognizing the trend of antipsychotic medication misuse in nursing homes, in 2012, the CMS established the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes, a public-private coalition to improve the quality of care for individuals with dementia living in nursing homes.

“Unnecessary antipsychotic drug use is a significant challenge in ensuring appropriate dementia care,” the CMS notes in a press release, pointing to data that showed in 2010, more than 17% of nursing home patients had received daily doses of these medications that exceeded recommended levels.

The mission of the partnership is to deliver person-centered, comprehensive and interdisciplinary health care that focuses on protecting residents from being prescribed antipsychotic medications “unless there is a valid clinical indication and a systematic process to evaluate each individual’s need,” CMS reports.

Better training, increased transparency and available alternatives to these medications are all approaches CMS has established to improve the situation. As a result, there was a drop in the use of these medications across the industry. Prevalence of antipsychotic use for long-stay nursing home residents fell by 40% between 2011 and 2019, CMS reports.

But over the past few years, use of these drugs has begun to creep back up ever so slightly, according to data CMS released in April 2022. This data also excludes patients who have a schizophrenia diagnosis, whether it’s a warranted diagnosis or not. The Times investigation found that when people with a schizophrenia diagnosis were included in the dataset, the decline in antipsychotic use that had been reported over the previous decade was about half of what had been stated.

Start With Non-Drug-Based Interventions

Still, in some situations, use of an antipsychotic might be appropriate.

“There’s some evidence that antipsychotics can be effective in treating physically aggressive behaviors,” Galik says, pointing to situations where an individual’s behavior puts themselves and those around them at risk.

For those who have a legitimate schizophrenia diagnosis, access to these antipsychotic medications is critical.

But, experts agree, in people with dementia who are acting out, the first line of defense should be behavioral intervention, not pharmaceuticals.

Skinner gives an example of a patient she worked with at a memory care facility years ago.

“This man had been a highly successful trial attorney, and he developed Alzheimer’s disease, and his family had him sent to a specialized memory care facility. And every day, he came out of his room, and he was very angry and agitated. He kept asking the staff, ‘Where is my office? Why can’t I find my office? I want to go to work. I need to go to work!’ And he kept this up every single day.”

The staff at the facility would respond that he didn’t have an office anymore, but that would just cause more frustration and agitation. This went on for some time before the director of the facility discovered a new solution. He asked the family to rearrange the man’s room to look like his old law office, with a desk and law books.

“And that completely defused the situation,” Skinner says. “When the man came out of his bedroom, he’d go to the dining room and have breakfast, and then he’d tell the staff he was going to work, and he’d go to his room. And in his mind, he was going to work in his law office. That was all it took for him to stop his aggressive behavior.”

This is a powerful example of how shifting a person’s focus can help them avoid medications they may not need.

“Interventions like these are designed to redirect the person into something purposeful,” Skinner explains. “Everybody — I don’t care who you are, as part of our human nature — we all need to feel that we have a purpose in life. Even people who suffer from dementia need to have that feeling too. That’s why these types of things should be offered to them.”

Non-drug interventions for dementia include:

— Music therapy. Music activates certain parts of the brain and can often transport someone to a previous time in their life via memories associated with the music. This effect can be calming in some people with dementia.

— Emotional reassurance. The Alzheimer’s Association recommends taking a moment to reassure someone with dementia if they become agitated. The organization advises backing off, asking permission of the person to assist them, remaining calm and offering positive, reassuring statements. Assure them they are safe.

— Distraction and engagement in meaningful activity. Skinner says distraction activities that help engage a person with aspects of their former life can be helpful. For example, “a great activity for somebody that was a homemaker is to offer them a basket full of towels and ask them to fold them.” The activity can be soothing and also gives the person that important sense of purpose.

Avoiding Overmedication

While there are certainly some circumstances where the use of antipsychotic medications is called for — and CMS acknowledges that the use of these medications shouldn’t decrease to zero — there’s still an effort underway to avoid overmedicating seniors with these powerful drugs.

“In my belief, there’s no medication that’s right or wrong. Medication is a tool,” Brownlowe says.

How and when a medication is deployed determines whether or not it’s being used appropriately.

For example, “when you have a nursing home that’s under-resourced, you don’t have enough people to take the time to provide personal care for someone who’s easily agitated and takes twice as long to work with that person to get them showered and cleaned up,” Brownlowe explains.

These seemingly simple tasks can be made more difficult if the patient is confused, agitated or uncooperative, so the medical team may receive a request from the caregiving team for a medication that quells these problematic behaviors.

“It’s not being done maliciously” in most cases, Brownlowe says.

Questions to Ask for Your Loved One

Because the use of antipsychotics in nursing home remains an ongoing concern and might be difficult for family members to spot, it’s important to check in with the care staff at the facility.

Brownlowe recommends asking:

Why is this medication being used?

It’s important to note that if your elderly loved one has always had a psychiatric disorder, the use of antipsychotics may be entirely necessary and appropriate. Typically, schizophrenia is diagnosed early in life, and treatment with antipsychotic medications in a nursing home is often a continuation of ongoing treatment that started years before.

“That’s not the category of patients in nursing homes that we’re talking about here. Here, we’re talking about patients who’ve received a new prescription later in life,” Brownlowe says.

What is the expectation of this medication?

What symptoms or issues is this drug supposed to address? What are the benefits that we can expect from this medication?

What are the side effects of this medication?

Whenever a new medication is prescribed for a resident, it’s important to ask questions.

“Families should feel comfortable asking about the indication of use of the medication, as well as potential side effects,” Galik says. “Both families and staff can help to monitor for potential side effects and report any concerns to the prescriber.”

What alternatives are there to a specific medication?

Before the medication is prescribed, ask if there are alternative therapies. After an antipsychotic is prescribed, ask whether a different medication can be used instead, particularly if it doesn’t seem to be helping or the side effects outweigh the benefits.

Who is making decisions about the use of antipsychotic medications?

“I think it’s really important for families and patients to understand who’s making these medication decisions,” Brownlowe says.

In some systems, she adds, it’s not always clear who’s making those prescribing decisions and why.

What else could be causing the problem?

Is there another condition that could be causing these issues aside from dementia? Brownlowe gives the example of a urinary tract infection.

“Older folks don’t always have the same symptoms (as younger adults),” she says. “Some of the early symptoms in older adults might be changes in mental status, confusion, agitation and aggression.”

If your loved one has exhibited a change in behavior, ask what else could be causing it. You should also ask for a comprehensive medical assessment, including blood work or a urine test, before jumping to use of an antipsychotic medication.

Is there an environmental trigger?

Brownlowe notes that for some older adults with dementia, communicating the underlying issue that could be causing aggressive or difficult behavior can be very challenging. The cause, however, could be environmental rather than physical.

“If the family member can identify, ‘Mom’s always hated things that are red,’ and the medical team says, ‘We just changed to new red scrubs. Maybe we can make an adjustment,'” Brownlowe says.

That’s a simple example, but the idea is to “take a look holistically at what’s happening before we jump into the antipsychotic medication bin,” she adds.

A good time to open this dialogue is during the care plan meeting.

“Families can share information with the nursing home staff about resident likes and dislikes, routines and meaningful activities that can be used to help prevent and manage behavioral symptoms of distress,” Galik notes.

Brownlowe also encourages folks to remember that “for the most part, everybody is doing their very best to provide good care. Everybody wants the best for the patient.”

More from U.S. News

Mental Exercises to Keep Your Brain Sharp

Health Screenings You Need Now

Antipsychotic Drugs in Nursing Homes originally appeared on usnews.com

Update 11/13/23: This story was previously published at an earlier date and has been updated with new information.