Late at night in the Singapore Strait, the five men quietly pulled their small speedboat alongside the bulk cargo vessel Vega Aquarius and climbed aboard the much larger ship. The men, armed with knives, were noticed by an on-duty crewman while they were on the stern of the deck.

The men rushed the crewman, who managed to escape after his cell phone was seized. Alarms were raised throughout the ship, deck lights came on and the ship’s full crew was mustered. A ship-wide search failed to find the thieves but revealed that two sets of breathing apparatus were stolen. The attacked seaman sustained minor head injuries.

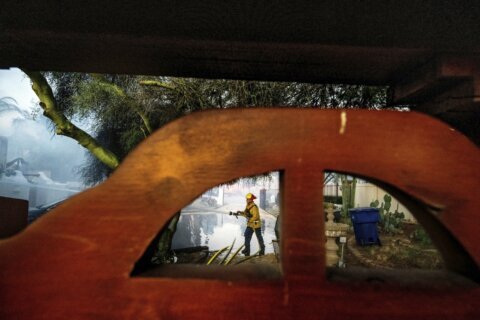

The May 9 attack on the Vega Aquarius, a Liberian-flagged tanker that was steaming from Singapore to China, took place just before midnight local time. But the robbery is part of a larger picture of attacks this year by armed men on the world’s high seas.

Pirate attacks across Asia doubled in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. In the Caribbean, maritime security officials say attacks have returned in the Gulf of Mexico. And a new, troubling trend is taking place off West Africa, officials say, with raids increasingly taking place far enough away from coastlines that they remain out of countries’ territorial jurisdictions, evading coast guard and naval forces.

Fueling further anxiety are hundreds of thousands of crew who are trapped working aboard the world’s cargo ships due to border and travel restrictions countries have imposed in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic.

And the pandemic itself is influencing piracy, experts say.

“We have seen an increase in piracy on a global basis and you can tie it to the pandemic,” says Rockford Weitz, director of the maritime studies program at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. “When the global economy suffers a downturn you generally see an uptick in piracy. We see impoverished people who are really worried about getting food on the table and who will take chances to feed their families.”

Sudden Rise in Attacks Across Southeast Asia

Maritime security officials who for years have tracked the global shipping industry are wary about sounding alarms of an overall rise in maritime piracy. And in fact, the number of worldwide incidences had been trending downward in the 21st century.

“We’re always a little bit cautious when we see some movements, because there is a general ebb and flow in attacks on the seas,” says Guy Wilson-Roberts of Risk Intelligence, a Denmark-based company that analyzes threats posed by piracy, terrorism and military conflicts. “The shipping industry gets used to ongoing threats. What they’re particularly interested in is something else, a change in the type of threat.”

Years of improving security measures aboard tankers, improved surveillance from the air and sea and increased international cooperation between countries’ navies had by 2019 pushed the global number of pirate attacks to a 25-year low, according to the International Maritime Bureau.

Reflective of increased international cooperation is the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against ships in Asia ( ReCAAP), an agreement created in 2004 that aims to quickly share piracy-related intelligence. Twenty countries, primarily in Asia, belong to the group, which also includes the United States, United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway, countries whose economies are heavily tied to shipping and trade.

But 2020 has seen a sharp rise in armed attacks at sea. Weitz, Wilson-Roberts and others who track maritime security acknowledge the increase in pirate attacks across Asia this year. Fifty incidents were recorded across Asia in the first six months of 2020, double the 25 reported during the same period last year, according to a half yearly report released earlier in July by ReCAAP.

The attacks are spread across a wide swath, from the South China Sea to off the coasts of the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Bangladesh and India. Most attacks have been concentrated in the Singapore and Malacca straits, narrow bodies of waters separating Indonesia from Singapore and Malaysia, respectively.

For centuries, both of the straits have acted as vital shipping lanes that connect trade in East Asia to ports in South Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Cargo ships are especially vulnerable traveling through the Singapore Strait, a congested body of water 65 miles long and only 10 miles wide that separates the island-state of Singapore and the Riau Islands that are part of Indonesia.

The waters feature many small islands with little or no people and government presence — perfect bases for criminals and terrorists to operate from.

Most of the pirate attacks there “center around robberies, stealing ship stores, crew valuables, whatever can be sold on the black market,” says Wilson-Roberts, speaking over the telephone from his offices in Vancouver, Canada.

The most high-profile incident in Asia took place in January, when pirates boarded a fishing trawler off the east coast of the Malaysian state of Sabah and abducted eight crew members. Six months later, five crew members are still being held in captivity.

Violent Attacks Off West Africa

On the other side of the world, off the coastlines of Africa, the security focus less than a decade ago was in the Gulf of Aden, regarded then as the most dangerous waters in the world. Somali pirates persistently hijacked large cargo ships. But a combination of coordinated international naval efforts, improved local governments and enhanced security measures aboard ships reduced the threat of pirates off East Africa.

Today, however, the Gulf of Guinea off the coastlines of West Africa provides the greatest worry for maritime security experts. Where Asia may experience the most piracy incidents, which are generally thefts, attacks in the Gulf of Guinea, particularly the Niger River Delta region, are dangerous for ships’ crews.

“The violence towards the crew is quite high and significant,” says Cyrus Mody, assistant director for Commercial Crime Services at the International Chamber of Commerce. “The incidents are targeted at the kidnappings of the crew and the attacks are a lot more violent than other parts of the world.”

While experts say piracy is generally under-reported — shipping companies can be resistant to reporting to insurers — the Gulf of Guinea presents extreme challenges in quantifying the scale of piracy. Mody says there is 40% to 60% under-reporting in the region of attacks on merchant vessels. And there is no accounting of attacks on fishing boats and passenger vessels inland on rivers.

Aside from the violent nature of attacks, Mody says many piracy incidents off West Africa are taking place farther out at sea — sometimes as far out as 70-100 nautical miles from coastlines — out of easy reach by coast guards and navies.

Adds Weitz: “Piracy is as old as human history. It’s really hard for us, given our land-based orientation, to understand how light the law enforcement is on the oceans.It’s a much bigger scale of a challenge than people realize.”

Trans-national Criminal Networks in the Americas

In the Western Hemisphere, pirate attacks began sharply rising in the southern Gulf of Mexico beginning in April. The attacks are primarily focused on ships and platforms tied to Mexico’s oil industry, robbing crews of money and seizing personal belongings and technical equipment that bring lucrative payouts in black markets.

The attacks in the gulf have persisted into the summer, causing the U.S. government in June to issue a special security alert for the region, singling out the Bay of Campeche as a particularly perilous region.

Weitz speculates that Mexico opening up its oil industry to international investment has led to that sector being seen as a lucrative target for attacks.

Other areas in the Western Hemisphere have also experienced pirate attacks. In April, eight men boarded the container ship Fouma at the port of Guayaquil, Ecuador, and fired shots at the vessel’s bridge. They seized items from shipping containers before racing off in two speedboats. Across the Caribbean, Weitz says trans-national criminal networks are targeting vessels at sea.

“The overall security situation in countries such as Mexico and Venezuela make it relatively easy for criminals to operate,” Weitz says. “And with the onset of the global pandemic, scant security and police resources are focused inland.”

Collaboration Seen as Essential Answer to Piracy

The global pandemic may also be affecting security aboard ships, experts say. Earlier in July, the International Transport Workers’ Federation estimated about 300,000 crew around the world are trapped aboard ships due to travel restrictions countries have imposed.

“The infection fear is limiting crew changes,” says Neil Roberts, head of marine underwriting for Lloyd’s Market Association in London. “Ships are very wary of pilots coming on board, and surveyors are having trouble accessing vessels to do surveys.”

Yet despite the rise in attacks this year, observers are upbeat about the long-term prospects of reducing maritime piracy. And certain countries are offering blueprints for other nations to minimize the threat. Fifteen years ago, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand entered into the “Eyes in the Sky” agreement, an intelligence-sharing pact that allows planes from the countries to fly over a certain amount of the other nations’ territorial waters in an effort to seek out pirates. The effort is generally seen as a success, Weitz says.

“Southeast Asia is doing very well. Although it’s not a perfect situation, if you look at 20-year trendlines it’s a success story.”

Such collaboration between countries is essential, experts say, because of the serious dangers piracy poses.

“People fantasize and romanticize piracy,” says the ICC’s Mody, speaking over the telephone from his London offices. “But it happens, and it has serious consequences. Seafarers who are going about their daily routines … they’re main job is to bring trade in and out. They are the ones injured, sometimes even killed.”

More from U.S. News

The 10 Most Corrupt Countries in the World, Ranked By Perception

Coronavirus Outbreak Throws Future of Global Trade Into Question

The 25 Best Countries in the World

World Sees Upswing of Maritime Piracy Amid Coronavirus Pandemic originally appeared on usnews.com