Rep. James P. Moran is quiet, speaking barely over a whisper, tapping his fingers on a conference room table.

It’s a side of Moran that many of his constituents haven’t seen since he was first elected to public office 35 years ago, as a city councilman in Alexandria.

The public image of the now 69-year-old congressman is that of a brash, fiery fighter, so much so that he was given a pair of boxing gloves by Arlington County Democratic Committee President Kip Malinosky at a dinner held in Moran’s honor in June.

The public image is neither incorrect nor complete. Moran has a legendary temper and passion, and he’s built a reputation of speaking “off the cuff” at public events, Arlington County Board Chair Jay Fisette says.

“He doesn’t read prepared statements,” according to Fisette. “He talks too long sometimes, but it’s authentic.”

That wasn’t always the case. Moran says he initially ran for office out of a fear of public speaking. He was unbearably shy, but wanted to help his community, so he gave it a shot.

“I dreaded speaking in public,” Moran told ARLnow.com, sitting in a conference room at Rosslyn’s ÛberOffices. “I fainted the first two times I did it.”

In one-on-one interactions, Moran is still the quiet type. “He’s a lot more soft-spoken than people think,” his former press secretary, Anne Hughes, says. He’s deliberate in conversation, thoughtful regarding each answer and, after he announced earlier this year that he wouldn’t seek re-election, reflective of his soon-to-be-ending time in politics.

*******

Moran was elected in 1990, unseating Rep. Stan Parris. Parris had served 12 years in the seat — from 1973-1974 and 1981-1990 — and was viewed as a significant favorite, but the district, and the country, was changing.

Parris, who died in 2010, had run for governor in 1989 and lost in the Republican primary, which Don Beyer — elected lieutenant governor that year — said “weakened” his campaign. Beyer is the Democrat running for Moran’s seat after beating out a crowded primary field in June.

Moran had already established a reputation as a progressive liberal — as mayor, he made sure that Alexandria would not discriminate against gays and lesbians in hiring for city positions — and Parris pounced on his opposition to the Gulf War, comparing Moran to Saddam Hussein.

When a reporter approached Moran on the beach after Parris made his comment, Moran said “that fatuous jerk… I’d like to break his nose.”

“He really wasn’t that bad of a guy,” Moran says today, “but he said a number of things that I thought were repulsive. I knew his voting record, which was terrible as far as I was concerned. I probably couldn’t have beaten him if I had known him because he wasn’t such a bad guy, but I didn’t know him.”

Moran says he woke up at 4:00 a.m. every day and drove to the Prince William County Park & Ride. At the time, commuters would drive to the lot and sleep in their cars before the bus arrived, to ensure a parking spot. The mayor of Alexandria would knock on their car windows and introduce himself.

“Normally I’d get the single-digit salute,” he says. So he continued to do it for weeks. “Eventually, they gave me the access to tell them what I was about.”

Moran also pressed Parris on his conservative views on abortion, a hot-button issue of the moment, even more so than it is today, Beyer says.

“It was the wedge issue in the campaign,” Beyer says. “Jim saw that opportunity and he seized on it.”

Moran won by a 7.1 percent margin over Parris. The district was re-drawn after the 1990 U.S. Census to make it more Democratic, and the margin will stand as the closest general congressional election he ever had.

*******

Once he entered Congress, Moran was immediately taken aback by the amount of influence money had over his fellow legislators.

Once he entered Congress, Moran was immediately taken aback by the amount of influence money had over his fellow legislators.

“I wanted to get the money out of politics,” he says. “I still do, but it’s gotten worse. I wanted to be transformational, in my naiveté. I was surprised at the influence that various interest groups had, domestically and internationally.”

Moran’s early years in Congress saw him build his reputation as a passionate legislator who’s not afraid to go against party lines. He voted against the original Defense of Marriage Act in 1996, one of only a handful of congressmen in either party to do so.

His lengthy track record on the side of gay rights caught the attention of Fisette and other LGBT rights advocates in Northern Virginia. Fisette and state Sen. Adam Ebbin — who are both gay — supported Moran against Parris and, after a couple of years in Congress, the two decided to ask Moran to make a splash.

“We got breakfast with him in Old Town,” Fisette recalls. “We thought, ‘let’s challenge him to do something.’ Our big ask was to ask him to consider hiring an openly gay person on his staff. He said, ‘you know, several times, I thought I had.’

“It was a great little moment that showed Jim’s character,” Fisette says. “I’ll never forget it.”

During his 1994 re-election campaign, Moran’s young daughter, Dorothy, was diagnosed with “a massive, malignant brain tumor,” he says. She was given a 20 percent chance of survival, and Moran’s wife at the time, Mary, “desperate to save her life… had 15 credit cards she maxed out.”

“She bought every concoction anyone said can cure cancer,” Moran says. “It was completely understandable. To make up for it, I started trading in options and hoping to outsmart the market.”

The end result was a “deep financial hole,” that Moran eventually paid off. Dorothy survived and, despite having a significant portion of her brain removed, is “doing well” and is engaged to be married.

*******

The early years of Jim Moran saw the fiery Massachusetts native draw controversy outside of the legislative arena. He was involved in a “shoving match” on the floor of Congress with then-Rep. Duke Cunningham (R-Calif.) over sending troops into Bosnia.

Moran ran into more financial trouble in the late 1990s after his divorce with Mary, and received a $25,000 personal loan from Terry Lierman, who he says “had been a friend since the 1970s.”

At the time, however, Lierman was a lobbyist for Schering-Plough Corp., a pharmaceutical company. Just a few days later, according to the Washington Post, Moran co-sponsored a bill to extend Schering-Plough’s patent on its allergy medicine, Claritin. A month later, he sent a letter to fellow Democrats urging them to support the bill.

Moran still denies that he took those measures as a tit-for-tat deal with his friend, and quickly re-paid the loan in full, he says.

Four years later, in the run-up to the second Iraq War, which Moran voted against, he told a crowd in Reston, “If it were not for the strong support of the Jewish community for this war with Iraq, we would not be doing this.”

He later apologized for the comments, and defeated a Democratic primary challenger, lawyer Andrew Rosenberg, the next year with 59 percent of the vote, his narrowest primary victory.

He’s also drawn accusations of impropriety over a mortgage he took out and a subsequent bankruptcy bill he supported, as well as allegations of insider trading. He forcefully denies that he’s given any special treatment or abused his power in any way.

“There are so many things people could be legitimately critical of me for,” he says, “it bothers me that [my detractors] keep bringing these things up that have nothing to do with my record.”

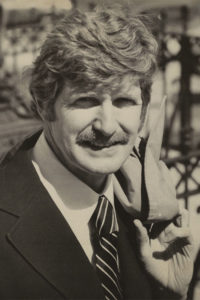

Editor’s note: This is the first of a three-part series. Parts two and three will be published Thursday and Friday of this week. Photos courtesy of Moran’s office.